New York City, January 8, 2018

★★ The sun flashed orange on eastern windows, then flooded apartments with golden light, then faded and died away under a dingy sheet of cloud. The snow was lumpy and begrimed, and the stabbing cold had dulled and dampened into something that sank in slowly and stayed sunk in. Something came from the clouds and left the pavement wet. A lump of slush fell from the bank building and splatted on the sidewalk.

★★ The sun flashed orange on eastern windows, then flooded apartments with golden light, then faded and died away under a dingy sheet of cloud. The snow was lumpy and begrimed, and the stabbing cold had dulled and dampened into something that sank in slowly and stayed sunk in. Something came from the clouds and left the pavement wet. A lump of slush fell from the bank building and splatted on the sidewalk.

Thousands Now Living Will Never Leave

By Jacob Riis – Museum of the City of New York, Public Domain, Link

The oldest extant reference to tourist enterprise on Hart Island, New York, the world’s largest pauper’s cemetery now in the process of slowly opening to the public is an account of a mid-nineteenth century prizefight. The combatants were James “Yankee” Sullivan and William Bell, and the account is documented in a multi-author pamphlet compiled in Sullivan’s honor in 1854.[1] The combatants chose the remote location, twenty miles north of Manhattan, as a precaution, given the uncertain legal status of prizefighting in 1842. Rather than setting a precise location in advance, the organizers depended on spectators to gather at predetermined spots along the river to the Island, and to follow the adversary parties to the final fight location. The ad hoc nature of this viewing space, and of the transportation procedures required to accommodate six thousand fight enthusiasts, did not result in ideal docking conditions:

[A] serious difficulty presented itself in the fact that there was no dock or other landing place, and the long, shallow, shelving shore made it dangerous for the heavily laden vessels to approach too near. The only mode of reaching land was by the medium of small boats, but many of the ardent amphibii, unable to wait their tedious turn, plunged headlong into the water and swam to shore. Thus gradually disembarked, the party streamed in one dense line in a N.E. course across the Island, and resembled, as they picked their devious way along, the writhings of a monstrous snake.

After additional complications arising from the need to create sightlines for six thousand spectators on a level patch of land, the fight commenced, and Sullivan defeated Bell after twenty-four rounds, claiming the three-hundred-dollar purse for himself.

All The Whites You Cannot Name

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Last year, I spent a month in the Arctic Circle, pretending to write fiction at an residency on the Norwegian island of Sørøya, a place with 79 residents and one ferry that runs twice a day, at most. Driven mad by the continual bickering of a dozen artists stuck indoors in a ramshackle old farmhouse, I escaped frequently to the Hammerfest Hertz. I rented anonymous little cars and drove around Finnmark on long rambling drives to small frontier-like towns and fish-scented ports. Toward the end of the month, I decided to go and see Russia. I didn’t have a visa for entry, so when I got to the border at Elvenes, I just stood there for a shivering half hour, gazing through a chain-link fence at the pristine snow, the skinny naked grove of birches.

I had been warned repeatedly to stay far from the border. Russian guards, according to local lore, liked to taunt people into stepping over the invisible line, then arrest them for their encroaching toes. This never happened to me, though I secretly hoped I would meet a cantankerous border guard with a thick accent and excellent outerwear. Instead, I just saw snow. Over 300 miles of snow, reached through hours and hours of driving through all-white, treeless landscapes, punctuated by the occasional house, the rare petrol station. I learned that colorless landscapes often are richer in tone than you might expect; that pink and blue and yellow shine so strangely from colorless crystals. Refracted and reflected, light bends and changes in the icy north. Color is gone, but color is everywhere.

New York City, January 7, 2018

★★★ The six-year-old kicked up his heels as he sprinted the route to church, spattering black slush drops up the backs of the legs of his pale corduroys. The snow was undiminished but beaten back; nice shoes could survive, if they weren’t too nice or didn’t have to go too far. Wool dress pants could hold off the still-brutal cold for a block or two. Where the salt and sun were strong enough, there was even some liquid water. Sherman Square had gone unshoveled, and inside its triangular fence was nothing but snow with a few hard-pruned sticks of shrubs sticking out of it. The wind came into the apartment lobby hard enough to shake the elevator doors and make the sensor open them again.

★★★ The six-year-old kicked up his heels as he sprinted the route to church, spattering black slush drops up the backs of the legs of his pale corduroys. The snow was undiminished but beaten back; nice shoes could survive, if they weren’t too nice or didn’t have to go too far. Wool dress pants could hold off the still-brutal cold for a block or two. Where the salt and sun were strong enough, there was even some liquid water. Sherman Square had gone unshoveled, and inside its triangular fence was nothing but snow with a few hard-pruned sticks of shrubs sticking out of it. The wind came into the apartment lobby hard enough to shake the elevator doors and make the sensor open them again.

Bad Farmer

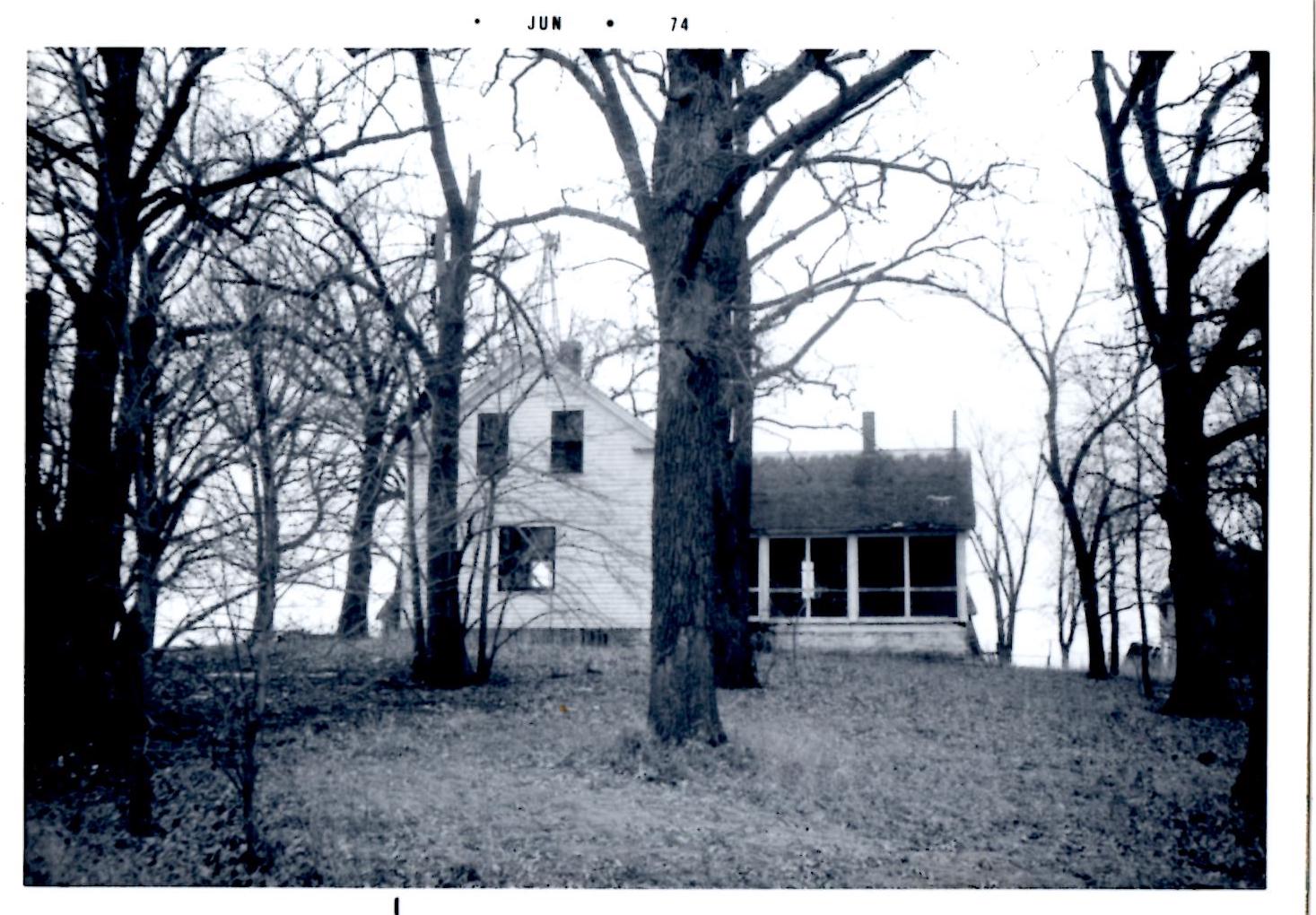

The farmhouse. All photos courtesy of the author.

Here is my earliest memory: my family is in the kitchen of the farmhouse where we lived before I was five. It’s late afternoon, but dark, because there’s a terrible storm outside. It could be a tornado, I’m not opening the door to look. The door is one of those flimsy aluminum jobs, and I brace myself against it as ferocious winds tear at our house. It won’t close properly, and I am holding it shut with the supernatural power of my tiny three year old body. We’re talking Wizard of Oz type weather, and I’m doing my part to protect the family. I’m not sure what the rest of them are doing, probably holding something down, but I’ve got the door thing handled. Just me. I’m on the door.

I don’t know. It doesn’t sound right, does it? I mean, I was three. You’d think the job of holding a faulty door closed against a tornado would have gone to maybe for example an adult. At the very least one of them could have been my spotter in case something went awry. I have some doubts that this memory is completely legit. Maybe it was just a dream I had when I was three. Or maybe I was playing some sort of game after having watched, perhaps the Wizard of Oz and was braced against a door on a sunny afternoon, yelling heroic things across the room to my family, who sat calmly eating cereal at the kitchen table. This whole moment in time can’t be trusted.

So maybe this is my earliest memory: My brother and I are leaning out an open window on the farm where we lived before I was five. We are attempting to break the sound barrier by screaming for our parents. There is blood dripping aggressively onto the windowsill, and I’m pretty sure it isn’t mine. That’s the memory; the view of tall grass and distant fields, the sound of two children screaming, the anxious feeling that spilled blood provokes. This memory has corroboration. My mother tells me that one day while she and my father were out in the field, I took a three foot statue of St. Anthony and cracked my brother over the head with it. They never heard us. They just returned to the house to find spatters and little bloody footprints trailed about the house. He was rushed to the hospital. Sounds like something I’d do.

We didn’t live on the farm for long, just a couple of years. We were brief experimental farmers in my father’s life long quest to abandon whatever he was doing. This wasn’t his first escape project. Before I was born he hauled my mother and infant brother deep into the north woods to live in a cabin. I hear there was a hole in the ground with a log over it they used as a bathroom. There are stories of mosquito infestations that rivaled biblical locust swarms. I dodged a bullet on that one by not yet being born. They moved back to the city when my mother got pregnant with me. She wanted to be closer to amenities like babysitting grandparents and plumbing. But dad was soon bored again, so he dragged us all to the country to become salt of the earth.

Change is Scary, But Not as Scary as Jellyfish

Image: William Warby via Flickr

“Everything in my life is changing! I don’t think I can handle all this change. What can I do?” —Troubled Tony

I fear change. Almost as much as I fear intimacy. I would say intimacy is first, followed by change, followed by dying. Dying used to be first. But then I was thinking about it the other day. Was I dead before I was born? I don’t remember feeling upset that I hadn’t been born yet. There was just nothing. I don’t remember the first bunch of years of my life. Then my brother hit me in the head from point blank with a wooden apple. I don’t remember a lot of stuff after that. But if dying is like it was before I was born, then that seems less scary. I hadn’t been born for thousands of years, I don’t feel one bit upset about it. And say there is an afterlife, and it goes on forever. That seems scarier. How long is forever? Will I always be fat and bald in this endless river of eternity? I think I’m more scared about the forever than I am the back to before I was born nothingness.

And intimacy! I barely have any idea what that is. But it scares the hell out of me. Like you’re supposed to let people into your life, let them know everything about you, what your weaknesses are, where you are the most vulnerable. And you’re just supposed to let them hang out inside there? When they’re not even drunk?

New York City, January 4, 2018

★★★★ It was not really possible to see the street where the closed school was, some two and a half blocks away. The snow was a smoke cloud, with little fast-moving thicker and thinner parts adding up to a blank gray whole. Figures picked their way along the dark trampled middle of the sidewalk. Out in it, the blown flakes were soft against the exposed part of the face, and the accumulation was soft underfoot. The drifts had wavy crests running along them. People were out and moving; the trains ran fine. The only locus of suffering was the Apple Store, with a closed notice at the door and workers dealing with a gleaming sheet of water on the floor. A bluish fog of snow came down through the grate onto the subway tracks. Rather than having been enchanted to a standstill, the city seemed pressed by the storm down to some active essence. After sundown, the snow was invisible but could still be felt very lightly on the face. The wind coming along behind it had nothing gentle about it at all.

★★★★ It was not really possible to see the street where the closed school was, some two and a half blocks away. The snow was a smoke cloud, with little fast-moving thicker and thinner parts adding up to a blank gray whole. Figures picked their way along the dark trampled middle of the sidewalk. Out in it, the blown flakes were soft against the exposed part of the face, and the accumulation was soft underfoot. The drifts had wavy crests running along them. People were out and moving; the trains ran fine. The only locus of suffering was the Apple Store, with a closed notice at the door and workers dealing with a gleaming sheet of water on the floor. A bluish fog of snow came down through the grate onto the subway tracks. Rather than having been enchanted to a standstill, the city seemed pressed by the storm down to some active essence. After sundown, the snow was invisible but could still be felt very lightly on the face. The wind coming along behind it had nothing gentle about it at all.

Plant A Tree And Get On With Your Life

I spent the first half of my twenties meticulously imagining the kind of person I wanted to be. Being very laid-back and in no way neurotic, I made lists of qualities and traits and habits I wanted to cultivate. For instance, I wanted to be a person who rose at 5:30 am without an alarm, reliant only on her finely tuned ‘body clock.’ A person who wrote ten pages freehand on a college-ruled legal pad before consuming a Spartan breakfast of unsweetened oatmeal and black coffee every day, even on Saturday. A person who never put off replying to important emails, who not only met deadlines but finished projects days in advance, not in a smug way, but just because that’s how she ‘worked best’.

But of all the traits I dreamed I would come to possess, the most aspirational was this: I wanted to become a person who never gave into—no, who never even felt—the urge to check her smartphone. I didn’t want to be a person without a smartphone—anyone could do that, and it seemed like both pretentious self-abnegation and a massive pain, baby out with the bathwater and all that. I wanted to be a person who owned a nice, glossy, convenient smartphone, but treated it like a utilitarian object, like a stapler or a shoe horn, a device that served its purpose when necessary and then was immediately, casually forgotten. I imagined myself as a person who would constantly forget where her phone even was, so engrossed would I be in my life of college-ruled legal pads and virtuous breakfasts and finished books.

Oh, the folly of youth! Who was I—a compulsively excitable, indulgent, distraction-prone night-owl, hungry for decadent breakfasts and easy stimulation—fooling? I love almond croissants and butter-laden eggs and I am weak before distraction, drawn to the bright lights and fast chatter and parading images of my smartphone. (On days I am being kind to my ego, I remind myself that these devices are designed to be addictive by literal evil geniuses, casino masterminds and conniving behavioral engineers and billionaires who wear novelty socks, and so I am not so much weak as predictable, programmable, a developer’s dream.)