How To Be Old: Two Women, Their Husbands, Their Cats, Their Alchemy

“Beauty is a responsibility like anything else, beautiful women have special lives like prime ministers but I don’t want that.”

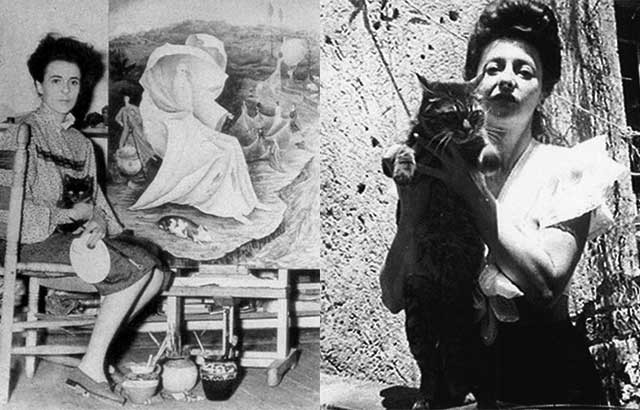

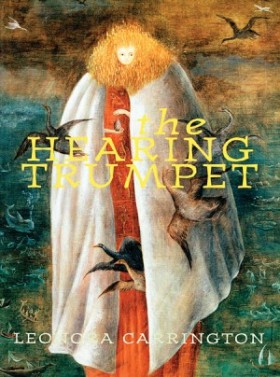

The writer and painter Leonora Carrington was 33 and a very beautiful woman when she wrote that line in The Hearing Trumpet, a book that is, among many other topics — alchemy, the Holy Grail, the perversities of nuns, the difficulties of getting goats and wolves to live together — also about being very, very old. This was in 1950; her best friend was a Spanish painter named Remedios Varo.

In the book, Carrington appears under the alias Marian Leatherby, who is 92 and has a beard. She has no teeth left and has become vegetarian “as I think it is wrong to deprive animals of their life when they are so difficult to chew anyway.” Varo is the magical, enterprising and rather dashing Carmella Velasquez. She wears a red wig in a “queenly gesture to her long lost hair” and smokes cigars between sucking on violet lozenges. When Marian’s family stows her away in a home for old ladies it’s Carmella who, comfortingly, takes over the care of her cats.

Carrington died a couple years ago, at age 94 — into her Marian Leatherby decade. Tomorrow would be her 96th birthday. When she wrote The Hearing Trumpet, she had, after a series of unlikely life twists, come to live in Mexico City. (The book contains her rueful, correct anticipation that she would never return permanently to England.) She was married with two young sons. In a letter written around this time: “… The Antichrists are antichristing each other with antichristly ferocity so I must go and make peace.” Like Carrington, Varo had come to Mexico from Europe during WWII. They visited almost daily.

In 1950, Varo was in her early 40s. She did not have children — she had cats, many, many cats and a series of lovers and husbands who, while diverting and sometimes quite impressive, did not, as a rule, have much more fixed income than the cats. (This would change with her last husband.) These men were amiable, though, and they remained devoted; she was the sort of person whose exes forever address her as “your admiring friend.” “My very dear Remedios … your hair is like the roots of invisible stars,” goes one letter. From a book inscription: “To Remedios whose two breasts are my two hemispheres.”

Still a few years away from her greatest successes as a painter, Varo supported herself (and the cats and others) in her first years in Mexico with commercial work. A partial list of her jobs, taken from Janet Kaplan’s essential study: She made dioramas for the war effort; she painted furniture; she created commercial art for Bayer; she did scientific drawings of insects; she designed and sewed costumes for the theater. (In Europe, while getting by in France at the outset of the war, she’d faked some de Chiricos and sold candy.) It has to have been a strain and a scramble, though what everyone remarked about her was her liveliness and extreme generosity. “These were not just nice ideas” — said one friend, of the works she undertook on behalf of others — “her head and her heart were united in an extraordinary way.”

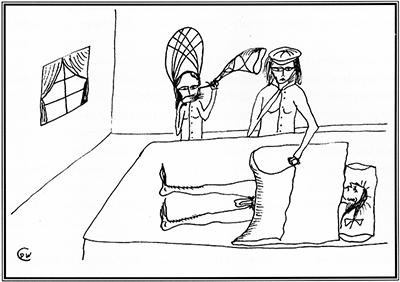

Carrington told one chronicler that she wrote The Hearing Trumpet in a café in the Plaza de los Mariachis “in the midst of cacophonous noise.” That seems fitting. As does the 26-year waiting period between its writing and publication. (The illustrations are by Carrington’s second son Pablo Weisz Carrington — which is funny, especially when he’s illustrating Marian’s cowardly son Galahad.) It has, as you read, the feel of a story dashed off by one friend for the express cackling amusement of another, a very particular Ideal Reader. The writing has a kind of glissading bumptious kangaroo splendor as it moves along but that beauty doesn’t seem summoned to formally impress so much as delight. The tone is jaunty and benevolently wicked: “Here we are at the end of everything. I have a beard, you have a wig! HAHAHAHAHAHA!”

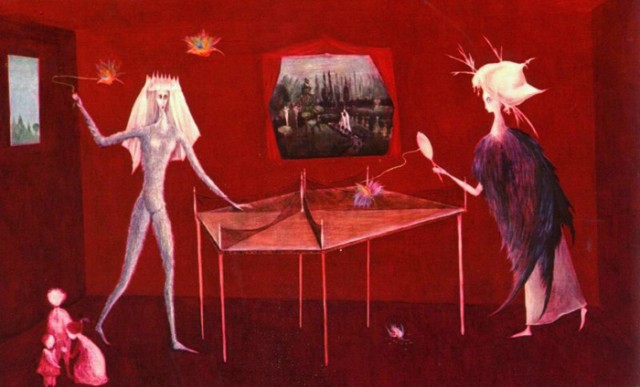

Crookhey Hall (1947)

Leonora Carrington liked fairy tales and nursery rhymes; and it’s wonderful how much of her early life obligingly flows in a fairy-tale vein. (Susan Aberth’s book on Carrington provides excellent background here.) She grew up in a house called Crookhey Hall, a Gothic mansion built by one Colonel Bird who, in honor of his surname, had bird ornamentation put in all around the place — and so Carrington’s first drawings began with birds. Her father was “the richest man in Lancashire”; he sold his textile company to what became a part of Imperial Chemical Industries, which, if you are going to have a remote, forbidding father, is exactly the board he should sit on. The Carringtons were only two generations into riches, though; his own father was a mill hand who had patented a valuable thingamajig. The family was, in other words, bourgeois, not aristocratic or intellectual. Her mother, the daughter of an Irish doctor, was Catholic. There was an older brother and two younger ones; their names seem unimportant. Of everyone and everything that existed at Crookhey Hall, Leonora later spoke lovingly of three things: Her mother Maureen, her Irish nanny Mary Cavanaugh, and her horse, Winkie.

By 17 she’d been kicked out of two convent schools and scraped through stints at finishing schools in Florence and Paris. She was allowed some time at a London art school. Here she is with her mother during her debutante season at their presentation at King George V’s court in 1934.

She later wrote the story “The Debutante,” in which the narrator sends a hyena to a ball in her place: “My mother came in, pale with fury. ‘We had just sat down to eat,’ she said, ‘when that thing in your place gets up and cries, ‘I smell a bit strong, eh? Well I don’t eat cake.’ Then she tore off her face and ate it. With one bound she disappeared through the window.”

Not long after the presentation, she’d met the surrealist painter Max Ernst, nearly 20 years older than she and married, and disappeared with him through the window to France, never to return.

“Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse

(1937–8) features a hyena. (It’s part of the Met’s collection.)

The photo below it was taken around the same time, in Cornwall.

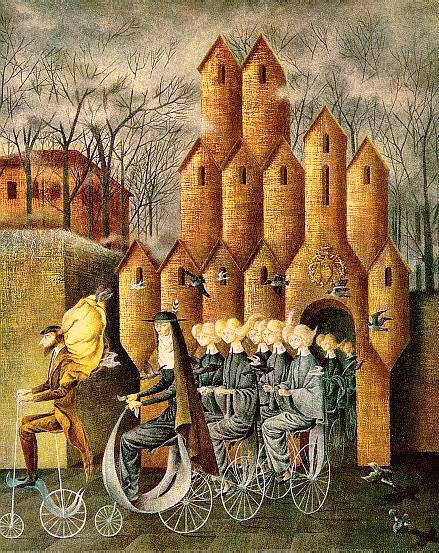

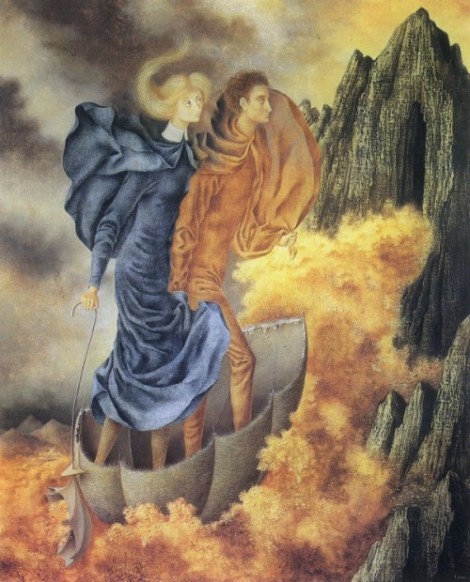

Remedios Varo also went to convent school, and she painted this autobiographical series about her school time. It’s impossible to see unless you’re up close, but in the second one, Embroidering Earth’s Mantle, the heroine of the triptych — the one who catches your eye in the first painting — has “embroidered a trick in which one can see her together with her lover,” which leads the way to the third painting.

Toward the Tower (1960)

Embroidering Earth’s Mantle (1961)

The Escape (1961)

Varo’s father, Don Rodrigo, was Andalusian; her mother Ignacia was Basque. Like Carrington, Varo preferred her mother’s company, finding her father domineering and crowding. He had ambitions for her. He was an engineer, and she learned draftsmanship from him. As Kaplan recounts, he frequently took her to museums as well as made her copy (and recopy) his mechanical drawings. This education stayed with her. Varo’s paintings often featured ingenious conveyances and other inventive bits of engineering (“pull that string and that odd-looking shell-like coat becomes a boat in which you can float away”), meticulously rendered.

For some reason this stray detail about her father’s life stands out as oddly poignant and funny: “Varo’s father was one of the few people in Spain to study the universal language Esperanto.” It gives a sense of the excess energy, the questing-ness that he passed along to his daughter. Here’s the melancholy father-daughter ride Caravan, painted in 1955.

Leonora and Remedios met at least once or twice in Paris before the war. They were both orbiting within the inner surrealist circle. Varo had fled Franco’s Spain with the poet Benjamin Péret, and Carrington was Ernst’s companion (to his wife’s vocal chagrin). They were both younger women in relationships with older, much more famous men. Varo described the period as one of “awe.” Carrington was less awed by the company: Joan Miró “gave me some money one day and told me to get him some cigarettes. I gave it back and said if he wanted cigarettes, he could bloody well get them himself. I wasn’t daunted by any of them.”

Surrealism celebrated the idea of the femme-enfant, the muse-like woman-child who, as Aberth puts it, “through her naiveté is in direct connection with her own unconscious and can, therefore, serve as a guide for man.” (Urf.) When Carrington arrived in Paris, she was embraced as the quintessential femme-enfant (and here we find that the young, striking-looking, confident and talented heiress will be warmly greeted most everywhere she travels). She later shrugged off the title: “I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse… I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.”

Still, she was in her early 20s; she was brilliant; she would have wanted all the other brilliant dazzling people to take notice. She went to one party dressed only in a sheet and dropped it mid-party. Out to a fusty dinner, she took off her shoes and spread the tops of her feet with mustard. And yet even as she and her paintings gained recognition, one part of her must have been standing apart and surveying the scene, thinking, thinking. (Even, or especially, about her relationship with Ernst, who had a knack for getting older while the femme-enfants stayed the same age. Or as Carrington put it: “Once you were over 25 you were pretty well out.”) The croneishness of bearded Marian and bald Carmella seem in the context of the femme-enfant like an extra good, extra dark joke. To repeat Marian’s line, “Beauty is a responsibility like anything else, beautiful women have special lives like prime ministers but I don’t want that.” The “I don’t want that” falls as she’s sifting around for a memory — but it’s obviously about more than that, too.

When the war came, Carrington was living with Ernst in a farmhouse in France.

(“Ah, Provence. … I was very happy there. I worked, I painted, I had a vine I looked after.”) They’d ignored the warnings of family and friends to leave. Once war was declared, Ernst was sent for interment in a camp with other German nationals. After his arrest, Carrington made her way to Madrid. The plan was to work for Ernst’s release there, but after a hellish journey, she had a nervous breakdown. “In the political confusion and the torrid heat, I convinced myself that Madrid was the world’s stomach and that I had been chosen for the task of restoring this digestive organ to health,” she recorded. She shared this theory with some authorities at the British embassy, after which she was committed to a Spanish asylum where she was given the anti-psychotic drug Cardiazol. This induced convulsions, and in that condition she was “left for days strapped to a bed.”

Eventually she was released. Meanwhile, her family had sent her nanny by submarine — let’s repeat that, sent her nanny by submarine — to fetch her and take her to an asylum in South Africa. Dutiful historian-ship forces me to mention that other accounts have it not being the nanny-in-a-submarine, but a business acquaintance of her father’s (transport uncharted — one can only hope dog sled) on the scene. Either way, Carrington gave her minders the slip by saying she had to go the bathroom, slipping out a café back door, hailing a taxi, and going to the Mexican embassy. There she had an old friend, Renato Leduc, who, in addition to his job as a diplomat, was a poet and friend of Picasso’s. He was also gallant. He offered to marry her, making it impossible for her family to force her anywhere. After a waiting period in Lisbon, they sailed to New York and then, after some time there, moved on together to Mexico.

(Ernst, released from detention, had been in Lisbon too, now in company with Peggy Guggenheim and her money. This waiting-for-passage period was by all accounts a dreadful, jealous time for everyone, including Guggenheim, who probably should have just hired a submarine to take herself out of there.)

Meanwhile, Varo and Péret’s wartime hopscotching took them from Paris to Marseille to Casablanca to Mexico City. The two were incredibly lucky to escape. Before leaving Paris, Varo was detained by the police for a few months. That time period, at least, is the most likely estimate: the actual specifics of her detainment are unknown, because she refused to ever speak of them. When she and Péret landed in Mexico City they found an apartment — you entered through a window and there were holes in the floors “we used… as ashtrays but you had to know where to step.” Varo pinned up the Picassos and Ernsts they’d come away with; she found work; she began assembling cats.

Once he performed his duties as a friend and escort, Leduc seems to have wandered off in some amicable, permanent way (I picture him just fading from sight as he goes down the block). In the crowd of Europeans in Mexico City, she met Chiki Weisz, a Hungarian photographer. Chiki was a nickname; his first name was Emerico. They were married in 1946 — in a marvelous photo of the wedding day, taken by their good friend Kati Horna, there is Varo grinning and peering over Carrington’s shoulder.

Antichrist 1 (Gabriel) came along later that year; Antichrist 2 (Pablo) followed in 1948. Her pregnancies were a great time for her painting. As she explained in a letter to her friend, the British art collector Edward James: “Inspired painting, I find, favors a rather bucolic and opaque frame of mind on a continually replenished stomach — preferably with heavy and indigestible foods such as chocolate, sickly cakes, marzipan in blocks… That is why I painted so beautifully when I was pregnant, I did nothing but eat.’’

James was extremely rich and eccentric; he was also one of Carrington’s first patrons, buying up many of her works and helping to arrange her first major show in New York, in 1948. (In The Hearing Trumpet he’s gifted a role as Marian’s mysterious and globetrotting friend Marlborough.)

About his first visit to her Mexico City studio he wrote:

Leonora Carrington’s studio had everything most conducive to make it the true matrix of true art. Small in the extreme, it was an ill-furnished and not very well lighted room. It had nothing to endow it with the title of studio at all, save a few almost worn-out paintbrushes and a number of gesso panels, set on a dog and cat populated floor, leaning face-averted against a white-washed and peeling wall. The place was combined kitchen, nursery, bedroom, kennel and junk store. The disorder was apocalyptic: the appurtenances of the poorest. My hopes and expectations began to swell.

The Giantess, below, was commissioned by James.

Bird Pong (1949)

The Giantess (1949) — yes, you recognize this from the Madonna video

Are You Really Syrious? (1953)

In The Hearing Trumpet, they’re Marian Leatherby & Carmella Velasquez. In a story of Varo’s, they’re Ellen Ramsbottom and Felina Caprino Mandragora. Ellen’s interests include “somniotelepathic phenomenon,” while Felina is “a goat when sleeping and a woman with ‘vague little horns’ when awake.”

In their visits to each other, they put together elaborate practical jokes. Other times, they “would just get together and laugh.” There were secrets, said one friend, “that Remedios would talk about with no one but Leonora.” They cooked together — and jokes became cooking recipes became “recipes that promised an array of magical results” — that is, spells — became inquiries into alchemy.

Varo in Mexico City.

One joke-recipe: Tapioca spritzed with squid ink, served as caviar. In an email, Aberth said they served this once to Octavio Paz: “He fell for it, much to their delight.” (This is one that seems, admittedly, like it was probably more riotous at the time; perhaps squid ink was more plentiful then, too.) Other recipes contained advice “for scaring away inopportune dreams, insomnia and deserts of quicksand under the bed.” A recipe for dreaming you were the king of England called for “a sable brush to paint egg white all over the dreamer’s body.” And here you will find Varo’s full recipe for erotic dreams, which includes as ingredients: “a kilo of horseradish, three white hens, a head of garlic, four kilos of honey, a mirror, two calf livers, a brick, two clothespins, a corset with stays, two false mustaches and hats to taste.”

Varo was busy with commercial work during this first blazing period of their friendship and so not painting as much as Carrington, but her notebooks are filled with the recipes, letters, stories, and plays written in a journal-y conversation with her. One dream description: “I am washing a blonde kitten in the sink of some hotel, but that’s not right it looks like Leonora wearing a loose overcoat that needs washing.”

A note from Leonora written in French on a drawing:

Remedios, I told you that I am making you a spell against [the evil eye]. There it is. Last night I had a fever of 38, auto-suggestion perhaps — I do not feel well enough to go out — Come to see me if you can? Can both of you come to drink your tequila? … Leonora.

I love the intimacy and lunacy of that note.

Here’s one very funny fact about Remedios Varo: She lied about her age. It’s not clear when it started, but, in her book, Kaplan suggests it might have begun when she was in Paris, among the surrealists, and feeling at 30 a little long in the tooth for a femme-enfant — so presto, magic, she became 25 instead. This age-shaving lasted even after her death: her tombstone gives her birth year as 1913, not 1908. (Interestingly, in The Hearing Trumpet, while Marian volunteers her own age, she doesn’t announce Carmella’s.)

In 1950, at 42 (or “37”), Varo’s life was taking a prosperous, happy turn. She’s gotten married to a businessman named Walter Gruen, who, unlike her previous affiances, was comfortably well off. Gruen pushed her to return to painting full time and show her work, which she’d been timid to do. A group show in 1955 and a solo one in 1956 brought her wide acclaim. This letter to her mother after the solo show is wildly triumphant: the show, she reports, “was a great success and there were hundreds of people. For my character this is rather painful. But I have sold all of my paintings and I am richer than a toreador. Because of this, whatever you fancy is yours for the asking…” I am richer than a toreador!

Photograph taken in Marseille in 1941.

Remedios died, very suddenly, in 1963 from what was almost certainly a heart attack. Some speculative talk circulated that it was possibly suicide — she was going through an anxious, fearful period — but that seems unlikely. One growing source of anxiety for her was aging. She frequently told friends about a Carmelite nunnery in Spain “where she planned to seek retreat if things ever grew too difficult.” (Carmelite/Carmella.) The convent was founded by an ancestor of hers, Don Rodrigo de Varo y de Antequera. But on a visit there, Kaplan discovered that she wouldn’t have been allowed entry.

As explained by one of the nuns, a disembodied voice speaking to her visitor from behind an impenetrable wall, although they venerate the memory of Don Rodrigo — keeping his cranial bones and portrait on permanent display — no worldly woman, not even one named Varo, could ever expect them to open their doors to her.

Given her great unhappiness in convent school, it seems perverse that Varo daydreamed of spending her last years sequestered in a nunnery: “Here is my masterful painting The Escape… then here is my next one called The Return.” But speaking to visitors in 2009, Carrington observed, “I miss England. … Although I probably just miss the past.” The twinned pattern here feels instructive: There’s the longing to disappear out the window; the bounding escape; then the realization years later that that window got shut firmly behind you.

But then: So what? There we are out in the world, me with this beard, you in that wig. HAHAHAHAHA.

Previously: How To Be A Monster: Life Lessons From Lord Byron