How To Be A Monster: Life Lessons From Lord Byron

How To Be A Monster: Life Lessons From Lord Byron

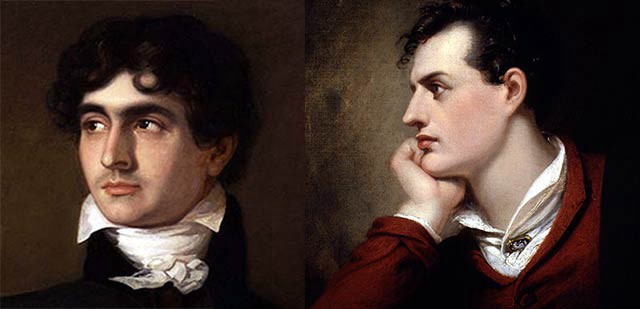

In 1816, a young doctor named John Polidori was offered the position as traveling physician to George Gordon, Lord Byron. Polidori was saturnine, caustic, ambitious, well-educated and handsome. He had graduated from medical school at 19 (as unusual then as now) and this offer came not a year later. Over the objections of his family, he accepted. Polidori had literary ambitions; here was an amazingly famous poet asking him to join him on a tour of the Continent. It must have felt like fate was tugging him along. In confirmation of how well things were going, a publisher offered him 500 pounds to keep a diary of his travels with the poet (500 pounds… in 1816).

It was spring. Byron was leaving England forever, a cloud of infamy hanging over him. (He is one of the few people you can write something like that about and have it be true; that is part of why he’s so satisfying.) He had a carriage made, modeled after Napoleon’s, this a measure of his own sense of emperor-like preeminence in the world. Byron was, even by the standards of the time, a chronic overpacker: china, books, clothing, bedding, pistols, a dog, the dog’s special mat, more books, a servant or two, and Polidori, buzzing like some excited insect, were all packed away. (One account has a peacock and a monkey making the trip too.) The carriage was so overloaded it kept breaking down. The doctor kept breaking down too, with spells of dizziness and fainting, and the patient had to look after him. They progressed this way through Belgium and then up the Rhine. When they reached their hotel in Geneva, Byron listed his age in the hotel registry as “100.”

If you have any interest in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or vampires or Romantic poets or, who knows, Swiss tourism, you’ve most likely read Polidori’s name. He’s a curio, Polly Dolly, most notable not for what he wrote but for being nearby when other people wrote things. It’s a strange afterlife; to think you’ve landed a leading role, and then there you are, on stage, sure, and with big names too, but fixed to a mark far upstage and over to the left, near the wings, in the half-dark where the spotlight doesn’t quite reach. “Poor Polidori.” That’s how Mary Shelley referred to him, writing years later. And he was. Here is how he creeps into letters, like this one written by Byron: “Dr. Polidori is not here, but at Diodati, left behind in hospital with a sprained ankle, which he acquired in tumbling from a wall — he can’t jump.” It was John Polidori’s misfortune to be comic without having a sense of humor, to wish to be a great writer but to be a terrible one, to be unusually bright but surrounded for one summer by people who were titanically brighter, and to have just enough of an awareness of all of this to make him perpetually uneasy. Also, he couldn’t jump. Poor Polidori.

One short story he wrote, though, remains important, a vampire story that was read across Europe when it came out and led the way to Dracula. But even that story was not all Polidori’s own. In a nice bit of literary vampiricism, he fed off a sketch by Byron to write it and the story was first published under Byron’s name (hence all the attention it got), so he’s instructive, too, as a reminder of all that writers and vampires have in common.

***

An aristocratic vampire bored by his immortality — we’re accustomed to that creature now. But this sort of vampire is relatively new. As Paul Barber describes in his wonderful book, Vampires, Burial, and Death, the vampires that populated European folklore for centuries were Slavic peasant and villager revenants, ordinary people rising from their graves bloated and ruddy, with long fingernails and grave dirt in their hair. Polidori based his story “The Vampyre” on a “Fragment” written a few years before by Byron. In each story, the vampire is rich, lordly, weighted down by dissatisfaction.

He is, in other words, a personage not so unlike Lord Byron. In Polidori’s story, the vampire, Lord Ruthven, has cold grey eyes. He is bored. It’s impossible to know what he’s thinking. He mixes in the highest society. He is well thought of, but, secretly, a predator eager to lead virtue astray. He and a young idealistic companion, Aubrey, set off on a tour by carriage of Europe. There is no mention of whether a monkey and a peacock are with them, but the rest of it sounds familiar.

“The Vampyre” was first published, in 1819, in New Monthly Magazine as a story by Byron. It created an international stir. A play and then an opera were based on it, events that seem unlikely to have occurred if the story had gone into the world as the work of a London physician. It’s widely assumed that Polidori passed the story off as Byron’s in an intentional imposture, but the evidence there is murky. Just as possible is that, the manuscript having passed through several hands after Polidori wrote it, the details of its connection to Byron grew confused on the way to publication. (Byron, breezily waving it off: “… I scarcely think anyone who knows me would believe the thing in the Magazine to be mine, even if they saw it in my own hieroglyphics.” He might just as well have added: “He can’t jump either.”)

Whatever his intentions there, the point remains that two years after he’d left Byron’s employment Polidori was writing a needling story based on Byron and using the vampiric character Byron himself had created to skewer him. It was like biting him with his own teeth. To add an extra silvery jab, he’d borrowed the name Ruthven, too. It came from Lord Ruthven Glenarvon, the villain of a wondrously batshit Gothic novel by Lady Caroline Lamb, a former lover of Byron’s. Her book was simultaneously a work of revenge and a provocation to renew an affair that had ended four years before: I hate you, let’s do that again. (It worked as neither. Instead of a ‘kiss and tell,’ Byron called it a ‘fuck and publish.’ After reading it, he neither returned to her nor was wounded in his retreat.) It came out in May 1816, as he and Polidori were first scraping into Geneva.

***

It was Caroline Lamb who called Byron “mad, bad and dangerous to know.” The level of celebrity he enjoyed when they started their affair was boggling. His future wife Annabella Milbanke termed it “Byromania,” observing that “the Byronic ‘look’ was mimicked everywhere by people who ‘practised at the glass, in the hope of catching the curl of the upper lip, and the scowl of the brow.’”

But Byron left England a monster, “a second Caligula.” Among his rumored crimes: He’d had a long relationship with his half-sister (leading to one child), carried on affairs with numerous actresses and married society women, and “corrupted” many young men. The rumors were all quite factual. He’d been engaging in such bad behavior for some time, but now the details were in wide circulation, Byron having committed the fatal error of marrying Milbanke, treating her abominably for the duration of their short marriage, then banishing her from the house a month after she’d had his child. Outraged, stonily disillusioned — if this were a movie she’d be played in these scenes by a thin column of dark smoke — Lady Byron hired a barrister and a gang of other counsel, including an attorney named Stephen Lushington, who, despite the delightful relaxed slurring suggested by his name, proved a prudent, sober and, alas for Byron, rather inexorable advisor. Lushington was shocked by all the secrets Lady Byron had to tell him. As Byron sailed, bailiffs were seizing what property remained at his Piccadilly Terrace home, including “his birds & squirrel.”

***

Lake Geneva: Blues and deeper blues. It was along the shore here that, one morning, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, his companion and soon-to-be-wife Mary (her last name Godwin still, not yet Shelley), and Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont were out walking. In love, electric, comet-like, Claire had seduced Byron with commendable dispatch before he sailed, then hurtled herself from England, hooking Mary and Shelley along with her, to await his arrival in Switzerland. Claire had left notes and letters of greeting for him at their hotel. Byron had ignored them. Now she was standing on the beach as he and Polidori returned from a morning excursion on the lake. As he clumped to shore, leaving Polidori floating in the boat, he didn’t yet know she was pregnant.

In a letter to his half-sister Augusta, Byron later wrote: “What could I do? — a foolish girl — in spite of all I could say or do — would come after me — or rather went before me — for I found her here. … I could not exactly play the Stoic with a woman — who had scrambled eight hundred miles to unphilosophize me.”

Here is Claire to him: “I know not how to address you. I cannot call you friend for though I love you you do not feel even interest for me; fate has ordained that the slightest accident that should befall you should be agony to me; but were I to float by your window drowned all you would say would be ‘Ah voila.’”

And here is Polidori, writing in his diary the same evening as the beach meeting, with characteristic blunt appraisal: “Dined, P[ercy] S[helley], the author of Queen Maab, came; bashful, shy, consumptive; twenty-six; separated from his wife; keeps the two daughters of Godwin who practice his theories; one L[ord] B[yron]’s.”

Shelley was actually 24, not 26, to Polidori’s 21. Mary was 16; although already she’d lost a child born prematurely and her second child with Shelley, William, had been born that January. Claire was newly 18. Lord Byron, the old man of the group, was 28. You can forget that about them — how astonishingly young they all were that summer. Not too long before Claire had been “Jane Clairmont,” then she became “Clair” before finally settling on “Claire” as alluring and sophisticated enough — that’s how young she was. Shelley had fled England with money problems, while Mary’s elopement with him and Claire’s involvement in it had cut off both girls from their home. Of the five people grouped together that day, only Polly Dolly had a family who would have welcomed him home unreservedly. In this light it doesn’t seem so surprising that they would soon all be writing about monsters (and in Mary and Byron’s case, quite sympathetically, too). Meanwhile, in the hotel and around the city, rumors circulated about who might be sleeping with whom (thrilling conjecture: everyone with everyone else). Byron’s notoriety travelled with him. When he attended a society party in Geneva, a woman fainted when he entered the room. (Byron would later downplay the drama of this episode by pointing out that the woman who had fainted was a novelist and that no sooner had she fainted than someone exclaimed, “This is too much — at sixty-five years of age!”)

To save money and regain some privacy, Byron moved from the hotel to the Villa Diodati, in Cologny, a few miles (or sail across the lake) from Geneva. Shelley rented another, smaller home nearby. It was a short walk between the houses, along a path that traversed terraced green vineyards. Hum of insects, cry of birds, smell of summer heavy in the air. Byron and Polidori were standing outside the villa one day when Mary Shelley approached up the path. Knowing the doctor had a crush on her; Byron urged him to jump down from where they stood and offer her his arm. He did, landed awkwardly and that’s how he sprained his ankle. Poor Polidori.

The fine days gave way to rain, which turned “incessant.” After a golden month spent boating and idling in the sun, the group was confined indoors. They read ghost stories aloud. Then, as Mary Shelley recounted it:

‘We will each write a ghost story,’ said Lord Byron, and his proposition was acceded to. There were four of us. The noble author began a tale, a fragment of which he printed at the end of his poem of Mazeppa. Shelley… commenced one founded on the experiences of his early life. Poor Polidori had some terrible idea about a skull-headed lady who was so punished for peeping through a keyhole — what to see I forget — something very shocking and wrong of course….

For herself, Mary says she thought and thought, and then, many nights later, in a state between waking and a dream, had the vision that led to her masterpiece Frankenstein, the story of a scientist whose fate is yoked to the wretched, stitched-up monster to whom he gave life. Byron’s ghost story remained a fragment, but he also wrote the poem “Darkness” that summer as well as the third canto of Childe Harold. (Infuriatingly if you were his companion, he started work on the latter while on the boat from Dover, while everyone else was being horrifically seasick.)

And there was Polidori with only his skull-headed lady to show (at least in Mary Shelley’s account). It’s easy to make fun of Polidori; he was capable, like so many terrible writers, of a sort of dreadful productivity and eagerness to read his works aloud: “later they suffered a reading of an atrocious play by Polly Dolly” goes a typical biographical scene. (After a few months of that you, too, might have been urging him to jump down from great heights.) His formal productions sound turgid, complicated… young; it’s too bad as that excessiveness would have worked against the bluntness that is so marked and funny when you read his travel diary. After meeting Stendhal: “a fat lascivious man. … He related many anecdotes — I don’t remember them.” About Belgium: “the country is tiresomely beautiful.” About Byron himself: “As soon as he reached his room, Lord Byron fell like a thunderbolt upon the chambermaid.”

***

Byron later described Polidori as “exactly the kind of person to whom, if he fell overboard, one would hold out a straw, to know if the adage be true that drowning men catch at straws.” Irritated and provoked, his manner toward him would metronome-tick back and forth between cruelty and apology. When Polidori sprained his ankle, it was Byron who carried him to the house, settling him on a sofa with pillows (a completely un-Byronic bit of solicitude). It wasn’t the only such stricken gesture. At no small expense, he hired a coach to take the young doctor around to Geneva society parties; another time he bought him an expensive watch. Over the summer, as Polidori got further out of hand, drinking too much and roaming around the villa, it was Byron who vacated the house. Who is the vampire in such a dynamic — who the victim, who the parasite? It switches back and forth, back and forth. Not hours after Byron was meekly plumping pillows for him, Polidori was again reading one of his plays aloud to the group. “All agreed it was worth nothing,” he recorded.

Out on the water, one afternoon, Polidori accidentally struck Byron in the knee with his oar. As Mary Shelley later relayed it, Byron “without speaking, turned his face away to hide the pain. After a moment he said, ‘Be so kind, Polidori, another time, to take more care, for you hurt me very much.’ — ‘I am glad of it,’ answered the other; ‘I am glad to see you can suffer pain.’”

On a side trip with Shelley, as the poets stood in “the middle of a beautiful wood,” Byron breathed out, “Thank God Polidori is not here.”

***

“Learn from me, if not by my precepts, at least by my example, how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.” — Frankenstein

Polidori and Byron parted ways in September 1816, after five stormy months in each other’s company. Polidori traveled on into Italy. He drifted. He took on a few more patients, returned to England, switched from medicine to studying law, and then, in 1821, died. He was 26. According to his family, he committed suicide by swallowing prussic acid after the pressure of some gambling debts he couldn’t pay grew too much. (At the inquest a family servant said in a statement that Polidori had recently suffered a head injury after “being thrown out of his gig.” This, too, may have contributed.)

Polidori’s father was Italian, a former secretary to the dramatist and poet Alfieri; his mother was English. Polidori had grown up among the expats of Soho; one great lure of the trip with Byron was the chance to see Italy. His sister Frances married Gabriele Rossetti, and was the mother of the poet Christina Rosetti and the poet/painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Their brother William Rossetti, also a writer, became the editor of Polidori’s diaries, although, like his siblings, he never knew his uncle. His work on the journals is oddly touching in its deftness and humor, like the penciling of an older, wiser Polidori surrogate. Of the position with Byron, William writes in the introduction: “The day when the young doctor obtained the post of travelling physician to the famous poet… must, no doubt, have been regarded by him and by some of his family as a supremely auspicious one, although in fact it turned out the reverse…. Polidori’s father had foreseen, in the Byronic scheme, disappointment as only too likely, and he opposed the project, but without success.”

***

Lord Byron died three years after Polidori, from a fever after having traveled to Greece to help fight for Greek independence. Long after news of Byron’s death reached England, people still reported seeing him on the street.

His “Fragment” is a slight thing, and yet the description of himself (for it is clearly a self-portrait) as the vampire is telling: “It was evident that he was a prey to some cureless disquiet; but whether it arose from ambition, love, remorse, grief, from one or all of these, or merely from a morbid temperament akin to disease, I could not discover.”

The pages, he later confided, had been written on an old account book of his wife’s, which contained “the word ‘Household’ written by her twice on the inside blank page of the Covers.” It was, as one biographer notes, “the only specimen Byron still had of his wife’s writing, other than her signature on the separation deed.”

***

Most of my first impressions of Polidori came from the asides and footnotes that appeared in other people’s biographies. Bits and pieces of a person. Read enough of these mentions (“mentally troubled man,” “embryo author”), stitch them together and a human form begins to take shape: a footnote Frankenstein. Of all the foototes, this one, from Richard Holmes’ The Pursuit, was the one where Polidori’s… essential Polidoriness most asserted itself. It’s attached to a sentence about Percy Shelley’s dislike for the Austrian troops then in Venice and so crops up as a non sequitur:

* Dr. Polidori was arrested in 1817 for asking a trooper to remove his busby at the opera.

Think about it, add it to your picture of John Polidori you’ve sewn together. Of course he was arrested in 1817 for asking a trooper to remove his busby at the opera. There he is, motioning from the wings. Vehement, insistent, even standing in the half-dark. He wants you to see him there.

Related: How To Give Birth To A Rabbit

Carrie Frye is here and here. Byron cartoon from this Hark! A Vagrant strip by Kate Beaton, used with permission; photo of Lake Geneva by Schnägglit; photo of Villa Diodati by Robertgrassi.