Don't Stop Running

I have never been a physically daring man. I’m afraid of heights such that my palms begin to sweat when I go up high flights of stairs in shopping malls. I’m awful at skiing, made slow and hesitant by an unyielding and morbid fear that I will propel into a tree or somehow shatter my femur in a devastating tumble. In middle school, when I joined the football team, in an attempt to realize my father’s thinly veiled desire that I be a quarterback, I was decidedly not one of the star players. To be very good at football, you need to be able to snuff out the voice inside of you that says it’s better for everyone if you do not hurtle your body at great speeds into another person’s body. I couldn’t squelch that voice, which only got louder after I watched a massive and overeager boy named Ryan bend my friend Mike’s leg the wrong way during a hitting drill, breaking it in two places.

Some people don’t have a voice urging reticence and caution. My friend Chris doesn’t, largely due to the influence of his father, Leo. Leo grew up in Tucson, Arizona, which at that time wasn’t even the mid-sized strip-mall Mecca it’s become today. Though in many ways he’d had an average middle-class upbringing, Leo’s father was an abusive alcoholic, prompting him to move away from home and get his own place as soon as he could put together enough money, which he earned laying pipe for a construction company. He married his high-school sweetheart, a half-Japanese woman with permanently rosy cheeks named Martha, and soon they were having children. Chris was first, and then his sister, Kelle.

When I met Leo, I was about six or seven. Chris and I went to the same elementary school and had become close quickly (“I think black people are funner and funnier than white people,” he once told me excitedly after we first started hanging out). We ended up enrolling in the same karate class so we could spend even more time with each other. His mom or dad, whose house was near our school, would drop us off, and my mom would pick me up later.

I remember being in awe of Leo, a short but solid log of a man, partially because of how different he was from my dad. After working as a pipe layer, Leo hauled scrap from construction sites for a living, while my dad was a lawyer. Leo, with his bushy handlebar mustache, usually wore jeans and work boots, while my dad favored pressed slacks and a clean-shaven face. Leo drove a pickup truck, and not in the way guys in big cities who want to play cowboy drive pickup trucks. Leo’s truck was caked in mud and scratched and dented, a victim of the abuses people and things receive in the desert, on dirt roads, around horses, around large men building things with their hands. My dad drove a Saab.

What I appreciated most about Leo, and what was most different about him from my parents, was how much time he spent in the outdoors. My father once said to me, “All the camping I need to do in this life I already did in Vietnam”; my mother, while lovely and doting, always preferred a bridge game to a fishing rod. I grew up a child who found many of my most enriching experiences indoors, in front of a computer or a book or a movie. For that reason, Leo’s stories about his far-flung wilderness adventures were exotic to me, stirring a curiosity deep from within, as if I were listening to an alien describe a cocktail party on the moon.

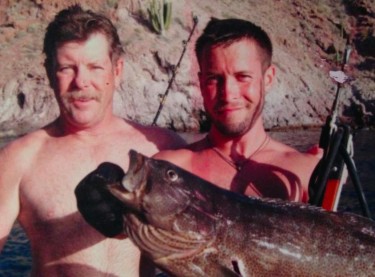

Besides pictures of his children, Leo’s walls were embellished with mounted heads of deer and javelina (small desert pigs) he’d killed with arrows and bullets, and then gutted himself. He angled on lakes and streams and the ocean, sometimes fighting for hours to reel in fish that were roughly the size of human babies. When mere rods grew tiresome, Leo would throw on snorkeling gear and leap into the water to fish with a spear gun. He skied on snow and water, and he scuba dived. Once, not having the slightest idea how to sail, Leo bought a small sailboat anyway and made Chris accompany him on the vessel’s maiden voyage. For half a day they got thrown haphazardly around a lake in northern Arizona by gusts of wind neither of them knew how to navigate, eventually capsizing the boat and having to wait for the only other boat on the water to come and rescue them. But tenacity prevailed, and by the time dusk began to settle on the painted rock formations ringing the water, the novices had become a halfway passable skipper and first mate. Soon thereafter, Leo was signing them up for sailing races in Mexico.

It’s impossible to be raised in such an environment and not emerge with a siren’s song in your guts and heart pulling you toward adventure and danger. From my father I took, among other things, a love of jazz and an affinity for wearing loafers with no socks. Chris took from Leo the desire — nay, need — to push his life to the limit. Besides sailing boats and going fishing and going hunting and all the other things Leo taught him to do, Chris builds and rides motorcycles; rock climbs, occasionally in the middle of the night; hikes the mountains around his house in Tucson; and cycles the softly sloping and winding roads that stretch out into various corners of the endless Arizona desert. To accomplish all of his various activities in a timely manner, Chris will occasionally demand his friends stick to a rigorous schedule — “Up at 8 and out the door by 8:30” and that sort of thing. He calls this “being a Leo.”

Chris, with his love of exploration and impulsiveness, has grown to be my closest traveling companion over the years, and thus, not incidentally, the major balancing offset to that cautious voice in my head warning against risk and bodily injury. Chris is the guy who, after spending all night barhopping in Budapest, demands you climb out the hotel room’s skylight and dangle your legs off the roof. Chris is the guy goading you into leaping from your hotel balcony to your passed-out friend’s hotel balcony in order to sneak into his room and obtain an iPhone charger. Chris is the guy driving his motorcycle 80 miles per hour five feet away from a sheer cliff drop on the Croatian coast. In late 2011, I ended up staring off a 50-foot rock looming over the Adriatic Sea in Dubrovnik. Below was Chris, who had already jumped and was now treading water while screaming at me.

“Just fucking do it!” he shouted. “Don’t think about it! Everyone’s staring at you! Aren’t you embarrassed?”

Knees shaking, I leapt, assuming the ocean floor would surely crumple my legs like breadsticks when I plunged through the water and hit it. But I came to the surface fully intact and trembling with nerves and involuntary laughter. Chris was beaming.

“Good job, buddy,” he said. “I didn’t think you were going to do it.”

“Were you scared?” I asked.

“I don’t really get scared,” he said. “And if I do, it’s already too late.”

With that, he kicked his legs and dipped his head underwater. Still shaking, I watched him swim a bit farther away from shore.

There is something about living life ultra-spontaneously — and some would say on the edge of reason — that is unshakably and clearly linked to death. I asked Chris once to what he attributes his dogged pursuit of thrills, what motivates him to walk on the edge both figuratively and, while prowling atop the roofs of Hungarian hotels at four in the morning, literally, too. “I’ve done everything I ever hoped to do in this life in just 30 years,” he said. “From here on out everything is icing on the cake until I die, and that makes me feel good.” I never asked Leo the same question, but I imagine he’d say something similar, although for a different reason.

Something many people didn’t know about Leo, and something I didn’t know until this year, is that he sometimes suffered through periods of serious depression and paranoia, buzzards that would appear and circle ominously over his otherwise charmed and charming life. Things got especially bad when his once successful trucking business, which at its peak was earning him six figures, began to flounder during President Obama’s first term. Leo started to believe it was Obama’s “socialist” policies that were ruining his small business, despite the fact that Chris’s own small business, a salon he’d opened in 2007, was flourishing. He begged Chris to not vote for Obama again, and, though he, Martha, and their children were all completely financially stable, he worried that he was not doing enough to provide for them. His mania eventually started to take over his whole life, drastically altering his behavior. In 2010, Leo, who had for decades welcomed me into his home and showed me very real love, was dragged out of a wedding by his humiliated wife after calling President Obama a “nigger” to an appalled group of Brits from the groom’s family.

At the end of February this year, Chris’ cousin, John, a cop, came out one morning to find Leo sitting in his car with a shotgun. “I wanted you to find me,” he told him. “I couldn’t have Martha or the kids find me.” John rushed Leo to the hospital, and later that day Chris went back to his childhood home to remove all of Leo’s guns from it. At the hospital, when the doctor asked Leo what was bothering him, Leo began, “Well, it all started when Obama got elected…”

In March, Chris and I decided to fly to Brazil for a vacation. I was in the midst of a frustrating patch at work and he thought some time away could help him clear his head of anxiety about his dad. We ate a lot and drank cachaça like mother’s milk. In Paraty, a cobblestoned colonial town that once served as a slave and sugar port, we rented a water taxi to take us to a restaurant on a sandbar. After we ate, we paddled a pair of kayaks to a tiny island populated only by rocks, some bushes, some cacti, and a few elongated and elegant birds that seemed totally indifferent to us. I remember looking down into the water, whose rich and layered darkness signaled some infinite depth, and feeling like I hadn’t done anything so important in months or years or ever. Cacti in the middle of the ocean, I thought. Imagine a thing like that.

We flew back to Los Angeles through Lima, Peru. We were sunburned and road weary, but still lightheaded the way you get when you’re coming coming down from shrugging off responsibility for a week or two. I hugged Chris goodbye at LAX, where he had to wait for his connecting flight to Tucson. I kissed him on the cheek and told him I was proud of him, and I told him I’d see him soon. A few hours later, while struggling to concentrate at work, I got the phone call from a friend: While Chris’ flight home was still in the air, Leo had hanged himself in his office. Several days earlier, Leo had tried to overdose on pills, but nobody told Chris for fear of upsetting him on his trip. After that, family members had been watching Leo in shifts as he fell deeper and deeper into depression. But he was determined, and he took advantage of a few minutes he found between Martha’s departure for work and his father-in-law’s arrival for the following watch. In retrospect, Chris says that he remembers detecting a certain tone in his father’s voice when he Skyped his family from Paraty one night. He says that in the back of his mind he knew his father had decided it would be the last time he was going to tell his son how much he loved him.

Some days I think perhaps the reason Leo stormed into life with such ferocity is because he thought something that was chasing him was gaining on him, and that when it caught him it would blot him out, eclipsing him and casting him into a darkness from which he would never emerge. Maybe he thought, just as Chris had that night that he was saying goodbye to his dad forever, that the end was coming for him much faster than it was coming for the rest of us, and that’s what led him to run so swiftly and eagerly in the opposite direction. If that’s the case, I wish he had known how many of us had been running with him and cheering him on.

Four days after we’d arrived in Brazil, Chris and I decided to go hang gliding. We took a cab down to a beach where a Google search had told us gliders congregate and, after 15 minutes, $100 dollars, and a few hastily signed release forms, we were in cars headed to the top of a mountain with two men who spoke hardly any English. The language barrier made it very difficult to understand even basic instructions about how to hang glide, with my handler, Paulo, saying only, “Just run, guy. Don’t stop running.” By that, he meant that I should not hesitate when it came time to run off the cliff. This is what Paulo’s English and my Portuguese were too poor to illuminate for me before we’d begun our ascent: To get a hang glider airborne, you stand about 40 feet from the edge of a cliff and run off of it at full speed.

The same voice that had paralyzed me years before on the football field once again crept up my stomach and into my throat, and I told Chris I didn’t think I could go through with it. “It’s not natural,” I said. “It makes no sense to deliberately fling yourself off a cliff.” Chris laughed at me and smiled the way he always does when I tell him about some fear that’s gripping me at that particular moment. And then, as he always does, he channeled Leo, whom in that second was thousands of miles away and probably far more scared than me: “Just jump,” Chris said. “And if you die, you died fucking hang gliding over Rio, so who cares anyway?”

In the end I ran, I jumped, I did not die, and I now think of the incident fondly for providing me with two of my favorite bits of advice this year: “just jump” and “don’t stop running.” If used figuratively, those vague enticements to action are the stuff of cloying motivational posters. I like to take them literally, however, and repeat them when faced with the physical feats that have always terrified me, preventing me from participating fully in this thing or that. In May, staring down a new cliff to jump off of in Hawaii, for once I didn’t hesitate when it was my turn to dive. That time I didn’t even need Chris, who was at home with his family, to yell at me and tell me that, though our bodies and minds are fragile, it is not a requirement to always treat them gently. There can be beauty found in calculated recklessness, and, for some, even clarity of purpose.

In 2013, I look forward to taking more grand leaps. And if my body should break and be killed on the rocks below, I hope I can be like Leo was and summon the courage to make the most of the fall.

Previously in series: Why You Should Not Use Twitter For Corporate Customer Service: A Cautionary Tale

Also by this author: The End Of The 00s: Family Business

Cord Jefferson is the west coast editor of Gawker.