The End of the 00s: Family Business, by Cord Jefferson

by The End of the 00s

For our purposes here, I suppose my father’s best story is the one about the time he became Larry Flynt’s lawyer. Wandering around a raucous party in Columbus, Ohio, in the early 1970s, my dad and his friends somehow found themselves in some dimly lit back room with Mr. Flynt, who at that moment was the very drunken but otherwise able-bodied purveyor of a booming chain of strip clubs. The consummate smut peddler, Mr. Flynt promptly offered everyone cocaine, and my father’s friends, some of Ohio’s best and brightest attorneys and judges, dove in with the zeal of men with half their responsibilities. While his friends huffed and puffed, however, my father politely abstained, choosing instead to hurry his tumbler of Scotch and head home.

The next day, his office phone rang. “This is Larry,” the caller croaked. “You’re the black guy wouldn’t do the coke, yeah?” My dad answered that he was. “That’s good,” Larry said. “I don’t need some horse shit junkie representin’ me. I can do that all by myself.” And so began my dad’s brief stint on retainer for America’s second most famous pornographer, who apparently marveled at my father’s avoidance of drugs decades before I would.

As he tells it, the only time my dad’s ever tried pot, he wound up trembling and hallucinating in the middle of a busy street near his law school, the lights and honking giving him vivid flashbacks of his most recent tour in Vietnam. He would later come to believe that the joint he’d smoked that night was laced with bad LSD; nevertheless, that one tainted experience was enough for him to swear off marijuana forever. “And you never did anything in the war?” I remember asking him, knowing full well that, had I been there, I’d have been trying to shoot up whatever I couldn’t shoot. “Never,” he said. “Killing people every day fucks you up enough.”

Growing up listening to my dad’s Miles Davis and Led Zeppelin records, I developed countless dreams of smoking grass with cats in Harlem and expanding my consciousness with the mud minions at Woodstock. That he had the opportunity to do all that and didn’t was a constant source of frustration and confusion for me, as if there was some river between us composed of bongos and bongs and liquid acid. But more than his immunity to the general lure of illicit drugs, the main reason I considered my father’s clean living so remarkable was because I was well aware of his unfettered appreciation for alcohol and cigarettes.

My mother will tell you that my dad “had a problem,” but I can’t be certain of where in that assessment truth ends and (reasonable) ex-wife embitterment begins. My father never got violent or drank vodka at breakfast or drunkenly crashed into our garage or anything; I can’t tell you with any shred of accuracy that he was some alcoholic monster out of a Southern Gothic novel.

What I can tell you about is the time my father pulled up to the ID checkpoint at our country club’s July 4th party with his right arm bent awkwardly behind his driver’s seat, his hand clutching a glass of Scotch whose ice tinkled cheerily two inches from my and my brother Derrick’s knees. I can tell you about seeing him light a Dunhill with a just-smoked, still-burning Dunhill, before ordering another pint at whatever restaurant it was this time. I can tell you about the night I got him by the lapels at the front door and shouted, “This is why she left, goddammit!” motioning toward the six-pack of Harp lager he’d brought into our newly motherless home.

And like a wife, a body can only take so much. The night my father lost consciousness and collapsed, in early 2006, the doctors told us to not panic, because it was still unclear what was happening to him internally. “Perhaps he’s just dehydrated,” they’d said. Relaying this information to me, my brother Trey’s voice sounded like mine had two years earlier, when, looking at a brand new Volkswagen I’d managed to jam under the rear tires of a dump truck, rendering it an immovable mass of shit, I’d called my mom and told her, “You know, I think it might be alright.” Like me, and unlike the doctors, Trey had watched our father spend decades filling his body with butter, salt, smoke, beer and brown liquor. He wasn’t just dehydrated.

A month later, the mystery was solved: it was the kidneys.

Renal failure works quickly, and within two years of his initial diagnosis, my dad, who was by then living and working in Saudi Arabia, was going to dialysis three times a week. The tiny filters in his kidneys had been mutilated by hypertension, and they were now operating at five percent of their normal capacity. So it came as no surprise when, in February 2008, my brothers and I received an e-mail whose subject heading was frighteningly brief: “Help.”

And it began: “I need your help. I need a kidney. I need to ask one of you for a kidney. So I’m asking.”

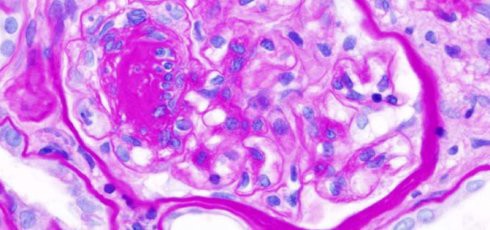

The message went on to expound on a lot of things, but, like grain and water and yeast, all of them could be distilled down to one thing: guilt. “I’ve not taken care of my body,” he wrote, “and that makes me angry. And for a while it made me think I have no business asking for your assistance in this matter.” In Riyadh, where a beer is as hard to get as a bikini, my dad was now dry, dying and ashamed. Hester had her letter-he had a pair of organs scarred with glomerulosclerosis, which were now silently destroying him from the inside like some traitorous fifth column.

“Fated” is a word that Florida Keys palm readers use, so I’ll not. Instead, I’ll just say I think it was weirdly helpful that I happened to be so shitfaced on whiskey when my dad asked me to give him an organ.

After a particularly bad week for a variety of reasons I can’t now remember, I returned to my Greenpoint apartment stumbling, bleary eyed and exhausted, my mouth and lungs feeling like the dessicated wallpaper in a house fire. This wasn’t a rare occurrence, but rather a habit I’d fallen into gradually-first in college, then in Los Angeles, then in New York. I opened my e-mail and began reading my dad’s pages-long message, which was difficult to get through because I had to keep returning to the beginning when my bloodshot eyes and beer-shot mind lost track of where I was. Finally reaching the end, which included the phrase, “YOU DO NOT HAVE TO GIVE ME A KIDNEY!” I sat and pondered what I’d read, angry at myself for taking in something so important instead of just passing out.

I considered my dad’s guilt, an emotion I’d once heard him call “worthless,” and an emotion which now throbbed in his kidneys. I recalled how angry I’d been at him for always ordering a beer at dinner and for never taking seriously the quit smoking remedies I’d clip from newspaper. And I remembered how weak my arms felt when I lifted my mother’s moving boxes. Mostly though-as is often my curse-I thought about myself.

Sitting in bed with my back against the wall, that e-mail looking up at me from my lap, I thought about the beginning of my own inclination toward inebriation. I thought about causes and effects, and I mentally marinated big ideas about morality until the room was bright with morning. Eventually, while fruitlessly trying find shame in being drunk while reading my dad’s e-mail about drinking, I finally latched onto something real, my most important discovery of the past decade: Human beings do singular things for about a thousand different reasons, most of which other people will never understand, even though it’s likely they do similar things themselves.

It sounds like a simple enough discovery, but for me it wasn’t. When you’re young, you’re taught that someone eats because they’re hungry, or yells because they’re mad; the narrative thread that connects thoughts and actions is short and sturdy. It’s not until you grow up and start making real decisions that you begin to comprehend the complexity of the web that connects a person’s heart and mind to their hands. And once you do that, thanks to innate inquisitiveness, you then feel the need to parse the whole thing down to bite-sized pieces. It’s this inclination that’s ruined so much news (“Columbine happened because of Marilyn Manson!”) and most movies (“The bad guy kidnaps people because he is evil!”), not to mention plagued me with questions throughout a large chunk of my adult life. I used to think my dad drank because he hated my mother, or because my brothers and I weren’t what he expected.

Not only that, but I pored over those possibilities in my mind millions of times, even when hearing that he was very sick and needed my help. To this day, that’s something I’m deeply ashamed of. Because when you begin to make peace with the fact that you can’t dissect the whole world, and you you truly decide to leave the mysteries enshrouding all bad things to the geologists and neurosurgeons, you’re left with a crisis mode that I’m probably paraphrasing Jesus to write: simply do right when you’re given the opportunity to do so.

But in these past ten years, I’ve found myself reaching for a bottle for a variety of reasons, most of which have nothing to do with anger or regret.

I’d like a drink every time someone tells me to “play the game and get on Twitter”; I’d like a drink when I have to have my salad weighed at lunch; I’d like a drink when extremely rich people lie to everyone and get away with it; I’d like a drink when I have to ask the drug store clerk to unlock the deodorant. I’m not necessarily mad when these things happen; they’re just some of my personal quotidian indignities that, if left unmitigated, would probably drive me insane. So sometimes I drink a few beers and forget about them, sometimes I write about them until I feel better-either way, I live to face them another day. I have no idea why my dad made himself sick, I just know that he did, and that I needn’t consider it when he writes me, dying.

On July 21, 2008, after a quick iodine shower, a surgeon cut a 10-inch incision into my flank and removed my left kidney. After a couple hours, in the very same room, that kidney was then inserted into my father’s abdomen. By medical estimation, the transplant extended my dad’s life by about 20 years. Even then, when I’m 46, I still don’t think I’ll know why my father drank and smoked so much. What I will know is the look on his face the day he came into my hospital room with a piece of me in his guts, forever. I’ll remember his eyes, wet with worry and hope, a zillion reasons for a beer resting just behind them, out of reach.

Cord Jefferson is a writer-editor living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in National Geographic, GOOD, The Root and on MTV.