The British Invasion... Again: The Amazing Evacuation

The British Invasion… Again: The Amazing Evacuation

by Robert Sullivan

Day six in a seven-day series exploring how the trail of the Battle of Brooklyn would pass across modern-day New York. Shown in photo, morning on Gowanus Bay.

On the American side, 2,000 rebels were killed, wounded or captured. On the British side, only a few dozen were dead. And so, back up on the Heights of Brooklyn, a mile’s stretch of water from New York, the Americans began the evacuation.

It would be over by dawn, and, until dawn, only the Americans will know. The British line that comes upon the last boats leaving will see a tall red-headed officer push off towards the island of Manhattan — it’s thought to have been General Washington himself. A Brooklyn woman, loyal to the British, found out in the midst of it; she instructed her slave, a young boy, to hurry to the British lines, but he was captured by Hessians who couldn’t understand his Dutch. Private Joseph Martin, a teenage Connecticut soldier who, after the war, wrote an account of all the Battles he had witnessed, from Lexington and Concord to the final British defeat at Yorktown, remembered the quiet: “We were strictly enjoined not to speak, or even cough, while on the march. All orders were given from officer to officer, and communicated to the men in whispers.”

They were marching from all around Brooklyn Heights, down to the water, to the ferry landing, from which point the army would cross the East River to New York.

The evacuation is the beginning of a new kind of strategy for Washington, who has to be convinced not to leave, who thinks maybe he can hold the British back. At a council of war in the Heights, his generals decide the danger of being cut off by the British fleet in the East River is too great. (Up to that moment, a northeast wind is holding the fleet back down towards the Narrows.) Amongst the new American troops brought in from Manhattan are the Massachusetts regiment commanded by John Glover, my personal favorite Revolutionary War general. Glover’s Marbleheaders are fisherman, boat-friendly, and they begin to row the artillery and then the soldiers across — one Marbleheader recalled eleven round trips, about 22 miles. Glover orchestrated the amphibious Crossing of the Delaware, and in some ways the evacuation of Brooklyn is the Crossing of the Delaware, Part I.

The British, considering the evacuation when it is over, had high praise. Edmund Burke wrote: “Those who were best acquainted with the difficulty, embarrassment, noise and tumult, which attend even by day, and no enemy at hand, a movement of this nature with several thousand men, will be the first to acknowledge, that this retreat should hold a high place among military transactions.”

The evacuation starts at just after dark and goes all night. A journal: “Unluckily, too, about nine o’clock the adverse wind and tide and pouring rain began to make the navigation of the river difficult… However, at eleven o’clock there was another and a favorable change in the weather. The north-east wind died away, and soon after a gentle breeze set m from the south-west, of which the sailors took quick advantage, and the passage was now’direct, easy, and expeditious. The troops were pushed across as fast as possible in every variety of craft — row-boats, flat-boats, whale-boats, pettiaugers, sloops, and sail-boats — some of which were loaded to within three inches of the water, which was ‘as smooth as glass.’”

Small craft beat the world’s most impressive navy — this is the take home point for me. And though the evacuation can seem slightly miraculous, as if it happened all at once, know that Glover had called for all the small boats along the East River to be moved to the Brooklyn side, earlier in the summer. He was ready.

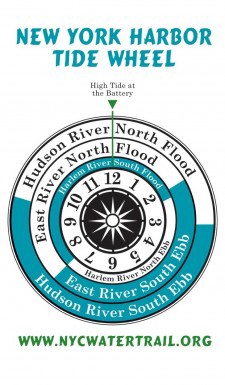

If you attempt to consider the evacuation from the vantage point of today, you have the advantage of having the tides of the harbor still in place, the rivers and straits and bays acting not to terribly different than they would have 236 years ago. Of course the Hudson flows faster, having more concrete walls than sandy beaches. (Only a few sandy beaches remain.) But if you check in with those in the boat community who have considered the evacuation, you will hear them argue that boats and men would have crossed, not in the straight line that the mind’s eye might imagine, but in the loops and arcs that winds and tides determine — the harbor is a wonderfully complicated system of currents, where there is no mere high or low tide, but many in betweens.

You will see that while boathouses have sprung up the city over the past ten years — in Long Island City and the Bronx, for instance — there are still nowhere near the number of boathouses there were in the 1930s, when, say, my dad was a kid, or before. The boathouses began to disappear in the 1930s, when the harbor was pollution filled, but now thanks to the Clean Water Act, in 1972, and a great interest in the effects of harbor-bound sewage outflows, people are trying to bring them back, despite some official reluctance.

You also notice that boating on the Hudson or the East River does not seem as simple as boating on other rivers other rivers around the country or the world. There are, for instance, permit requirements in New York that are, in the opinion of many boat activists, legally dubious. Why are we not on the water all the time, given that in terms of open area, the water in New York City is the Sixth Borough?

I have spent the past couple of years thinking about this, rowing in the old Whitehalls that anyone can row in, out at Pier 40, in Manhattan. I have gone kayaking by partaking in the Village Community Boathouse’s free kayaking program in the Dumbo section of Brooklyn. And I have gone to other cities and used their boats, jealously. It’s easy to be on the water in New York, as well as fun, and, with some safety precautions (most importantly, life jackets), it is easy not only to imagine the evacuation of Brooklyn in 1776; it is easy to imagine a revolution in which we, as New Yorkers, take back the waters of New York, instead of leaving it to highly regulated privately run quasi-public parks, funded by commercial development.

Recently, on a very hot day, I went out in a boat on the Gowanus Canal, to take a trip around Red Hook, past what would have been Fort Defiance, a Continental Army battlement, through Buttermilk Channel and into Brooklyn Heights. It was the trip the British Fleet wanted to make but couldn’t due to the wind in August 1776. We had a lot of wind fighting us, but we also had the tide, thanks to the organizer of our trip, Marie Lorenz. Marie is an artist who uses her handmade boat to take advantage of the tide. I was also with Tim Harrington, a member of Les Savy Fav. He is our mutual friend — Marie knows him from art school, during which he once asked her to help tie him to a fence upside down and leave him there, to startle passersby.

We went out at dawn, and at first it felt as if we were escaping something, and then, when we got out into the Gowanus Bay it was very peaceful. We saw a giant cruise liner, a night heron, fish churning the water. Tim spotted a taco truck on the police evidence pier, a prisoner. We passed very near the onetime location of Fort Defiance, today recalled in the name of one of my favorite restaurants, and we could see down a street towards the Sixpoint Brewery, the six points reminding me of a 18th-century fort layout, even though the six point star is an ancient brewer’s mark that combines alchemy’s symbols for earth and air, as well as male and female. We eventually got out at the new Brooklyn Bridge Park, one of the new part private, part public parks. The side of the sign that faced the shore said that only permitted activity was permitted. The side that faced the water didn’t say anything. We got out.

But on the morning of the 236th anniversary of the evacuation, I went out early and just stared at the water down by the ferry landing under the Brooklyn Bridge. There were couples taking wedding photos, tourists, park workers who are not employees of the private-public park but are outside workers contracted to pick up trash. And there was the water of the harbor. The water is exactly as the Greek philosophers saw it: it is yesterday’s rain in the Catskills and tomorrow’s Atlantic Ocean. Given the tides, some of it was yesterday’s Atlantic Ocean. Tide, by the way, comes from the Old English word tīd, meaning, you guessed it, time. To look into the harbor is to glimpse back and forward in time.

This is what Walt Whitman was talking about, if you ask me, in the section of Leaves of Grass known as “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” (audio):

It avails not, neither time or place — distance avails not;

I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence;

I project myself — also I return — I am with you, and know how it is.

Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt;

Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd;

Just as you are refresh’d by the gladness of the river and the bright flow, I was refresh’d…

Previously: The Landing In New York, Scouting Old Locations, The General And The Moose, The Battle Begins and The Mystery Of The Missing Marylanders’ Graves

Robert Sullivan is the author of a several books, including Rats, How Not To Get Rich, and The Meadowlands. His newest book My American Revolution will be published Sept. 4 (next Tuesday!) and is available for preorder.