The British Invasion... Again: Scouting The Old Locations

by Robert Sullivan

Day two in a series exploring how the trail of the Battle of Brooklyn, beginning with the British landing on August 22, 1776, would pass across modern-day New York. Shown above, the hills of Greenwood Cemetery.

In the lull before the battle — the first battle of the Revolutionary War, the 236th anniversary of which is coming on August 27th — it made sense to go out and look around, like a scout. A general on the side of the Americans would have used this time to survey the landscape, to traverse the hills and woods of Brooklyn and into New York (here are the receipts Washington sent to congress for that very job). Whenever I’m out and about, I try to see the areas as they might have been, and what I’ve often found is that: the old landscapes are closely related to the current one, sometimes the same, especially in the big picture.

In my own case, there is obviously less urgency that there was for the commanders of the Continental Army. I take it slowly. For me, this is a recreational pastime, like a long chess game, or hiking the Appalachian Trail; glimpses of distances, understandings of relationships in topography are like hard-earned thrills. I feel as if I have an insight in to the city’s old landscape every few months or sometimes once in a few years. Most of them are no-brainers, and if you live on the block that I am thinking about or standing on, you would surely consider any insight of mine to be obvious. But for me, these spots are all over, geo-cached, and I am finding that in a campaign that lasted a lifetime you would be hard pressed to see them all.

Sometimes friends call me to show a view I would never have found on my own. One winter, I had a friend who’s an ecologist call me out to Alley Pond Park in Queens. The word ‘alley’ describes a valley through which George Washington is said to have come through at one point, probably to get a boat out of Flushing Bay and over to Manhattan. It’s a big park with an old and productive forest; you can see owls there that make you feel as if you are far away in New Hampshire.

I took the Long Island railroad out to the Bellerose station, the place I played stickball as a kid, and walked a mile or so, finally crossing beneath the Grand Central Parkway to enter the park. This is a park that happened to play a strategic importance in my childhood landscape; when people on my block trapped squirrels in their attics, they took them to Alley Pond, to be set free. Across the street was a state mental-health facility, Creedmore, which mesmerized us as kids. Unbeknownst to me Woody Guthrie was a patient there when he died in 1967, after which his ashes were sprinkled off Coney Island. Just past Creedmore, I met my friend and walked to a parking area that is just alongside the Grand Central Parkway, and he pointed southeast.

“There,” he said. It was a widescreen view to Long Island, a look out on the plains that make up the neighborhood called Jamaica Plains. Because we were close to two hundred feet high, we could see out past the sparkling water of Jamaica Bay National Wildlife Refuge (home to more bird species than Yellowstone and Yosemite combined) and well down the southern shore of Long Island. We had front row seats in an amphitheater that looked out on the harbor and the Atlantic. It was an amazing view and it existed because we were standing on the terminal moraine. The Battle of Brooklyn played out along the moraine; if the Battle of Brooklyn were an HBO miniseries, the glacial moraine in Brooklyn would be an early set. (Once a local filmed it low budget with kids on bikes.)

The city itself, the rocks of it, are, grossly put, a combination of two big geologic stories — one that is a vertical story as you look down at the map (see the northeast trending valleys that create the East River the Harlem and Bronx rivers or the Palisades along the Hudson) and one that is a horizontal story: see the glacial moraine as it runs through Brooklyn and Queens, a miniature two-borough mountain range, usually invisible unless, say, you go to Ridgewood Reservoir in the fall and take in the amazing view of Manhattan on the one side, most of Long Island on the other. The vertical geology is the result of stresses and fractures that are related to the very old Appalachian Mountains; the horizontal geology is related to the not-as-old Wisconsin glacier, which pushed a lot of junk to New York from elsewhere and left the forward hills as if marking how far it had gone. In Central Park, it all mixes, and, as tour guides and land artists often note, you can see the glaciers scratches on the rocks: “Imagine yourself in Central Park one million years ago. You would be standing on a vast ice sheet, a 4,000-mile glacial wall, as much as 2,000 feet thick,” wrote Robert Smithson.

In the days between the first British landing on Brooklyn and the face off itself, Washington and his staff could only make guesses as to what the British were thinking, as to whether the war would be fought in the glacial landscape, you might say, or the Appalachian one. Washington seems to have thought maybe the British were faking a Brooklyn battle, getting ready to swing in on the East River, or the Hudson. He had did not yet realize that there were upwards of 32,000 Redcoats preparing to march against his 10,000 poorly trained, gunshot-happy men. The Americans had built forts all along the moraine; the idea was to hold the Redcoats back at the passes, the cuts in the glacial hills. There was a fort in Brooklyn Heights, near the Promenade. There was a fort at the top of what would become Fort Greene Park.

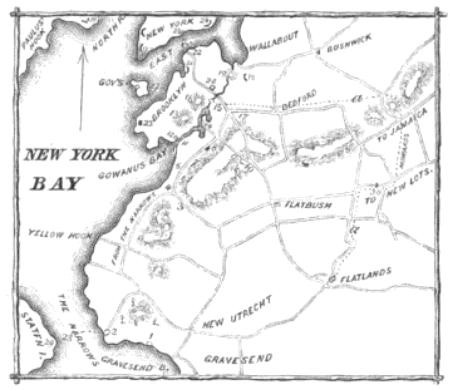

A map detail from The Pictorial Field Book Of The Revolution

.

The fort that is marked today by a plaque in front of the Trader Joe’s at the intersection of Court Street and Atlantic Avenue was called the Ponkiesberg Fortification — Ponkiesberg is Dutch for Cobble Hill. Where today people line up as if in a Great Depression-era relief line before the store even opens to buy discount organic food, there were once soldiers from New England building a fort on a plot of land that was then a little higher (the British had some prisoners chip down the hill after the Battle of Brooklyn). Whenever I see the line, I am reminded that Trader Joe’s is owned by the family trust of someone who fought against the American army during WWII, Theo Albrecht, who had served in Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, in Tunisia, where in 1945, he was captured by the U.S. Army.

After the soldiers built the fort, Washington and his generals, spent a lot of time looking back towards the British, to count British campfires, to scan the horizon with their spyglasses, always Washington has his spyglass. Meanwhile, they sent scouts out into the woods and fields. The historian I. N. Phelps Stokes in his monumental historiography of the Revolutionary War, written between 1915 and 1928, quotes the journal of a soldier, Jabez Fitch, writing after the British landed: “I this Forenoon, Observ’d several peculiar Smoaks, arising at Different places on Long Island…,” he wrote. “About Sunset we March’d forward, & pass’d ye Lines or Breast Work, soon after which were ordered to Load our Pies [guns], Our Reg’t & Col Tylers . . . took Post in a large Wood, where we spent ye Night; not a Man Allowed to Sleep a Wink, or put his Pies out of his hand.”

Where were the woods? How can I see the woods? Can I reenact the hills? Or re-place myself in them? These days, there are a lot of people trying different sorts of Battle of Brooklyn reenactments. See, for instance, the 2010 assault by the street artist General Howe.

But I like to just get out on my bike and look around, in the days before the battle. A couple of years ago, when I was searching for something that resembled the old Brooklyn hills, tree-covered and hilly, I hit pay dirt in Sunset Park. So for today, I headed out there again, bringing my camera, to shoot.

I biked from the Brooklyn Bridge out past Trader Joe’s, dodging double-parked cars. Then I went down into the Gowanus watershed, past the future canal-side site of Whole Foods. I headed slowly up the moraine to Greenwood Cemetery, a grind. As you reach the top there are spectacular harbor views; if you are me, you can’t believe how high up you are. For years, the cemetery has hosted a formal reenactment of the Battle of Brooklyn. But I don’t go into the cemetery. Rather I head down to around 30th Street, on Fifth Avenue, and just look in. There are hills and trees that shoot backwards, and I never have to leave the present, or wear a tricorne hat and wig. Cemeteries are known as repositories of old breeds of roses, and this is a case of a cemetery being a repository of an old landscape. When I got there on this foray, I pulled out my camera to take a photo, and was shocked to see that I was out of battery. I panicked, until I remembered I had my phone. I left victorious.

Previously: The Landing In New York

Robert Sullivan is the author of a several books, including Rats, How Not To Get Rich, and the Meadowlands. His newest book My American Revolution will be published out Sept. 4 and is available for preorder.