The British Invasion... Again: The General And The Moose

The British Invasion… Again: The General And The Moose

by Robert Sullivan

Day three in a series exploring how the trail of the Battle of Brooklyn would pass across modern-day New York.

On August 24, 1776, there is not a lot going on fighting-wise in Brooklyn.

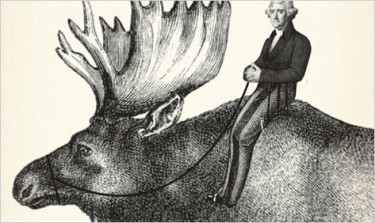

There are skirmishes amongst the woods and the farms where the British have landed, but Washington still has not figured out how huge the British landing is. He has sent General John Sullivan over to Brooklyn, a general who will be captured when the Battle of Brooklyn begins and will have a controversial record there after, despite several victorious battles after the crossing of the Delaware. Sullivan would wreak havoc on Native American settlements in western New York state, during the so-called Clinton-Sullivan Campaign of 1779 . But what I remember him most for are his dealings with the Comte de Buffon, aka George Louis Leclerc, France’s leading naturalist at the time of the war. Those dealings started, post war, in 1786, when Thomas Jefferson, America’s ambassador to France, wrote to Sullivan asking him to send him a moose. This was not a joke.

This moose request by Jefferson had to do with Buffon’s ideas regarding American flora and fauna. Buffon believed that North American animals were like European animals, though not as big or healthy. (This is analogous to the Republican Congress’ observations of Frenchmen versus Americans during the presidency of George W. Bush.) Buffon argued that the American landscape degenerated animals, and, from a PR standpoint, Jefferson felt that was not good for young America’s image. Jefferson, who, like just about everyone in Congress at that time, was himself a naturalist, and he worked to disprove Buffon’s theories, compiling lists of animal dimensions. “The Elk of Europe is not two-thirds of his height,” he wrote.

He sent Sullivan specific notes on how to mail the moose to France, and Sullivan sent skin and bones, as well as horns that were perhaps from another moose, which was good enough for Jefferson, who patched it all together and delivered it to Buffon, who was in charge of French natural history museum. Jefferson apologized for it being a relatively small American moose. Buffon promised Jefferson he would set thing straight in writing, but Buffon very soon thereafter died. As Gaye Wilson wrote in “Jefferson, Buffon, and the Mighty American Moose” (pdf): “Jefferson as diplomat, scientist, and citizen went to unusual lengths and personal expense to dispel unfavorable myths about his country by attempting to prove once and for all that the American moose was indeed unique and definitely bigger than its European counterparts.” Which is something I personally always try to give Jefferson credit for.

As far as the natural history of Brooklyn goes, Sullivan’s men were stationed in some woods near today’s Ditmas neighborhood. They were moose-less woods, but they were woods, highlighted by one tall oak tree well known as the Dongan Oak. This tree was named for Thomas Dongan, governor of New York in the 1680s, the Irish parliamentarian who called the first the first representative legislature in New York state. The tree denoted the eastern border of the town of Brooklyn. Sullivan’s men would cut it down to block the path from Flatbush, today known as Flatbush Avenue. Tall trees then, as today, mattered to people.

But the note of natural history that I have been working toward has to do with trees in the harbor. Yes, trees in the harbor. I am not talking about a sunken forest, or flotsam and jetsam. I am talking about trees floating. This may sound impossible but consider the diary of a colonist who looked out on the British fleet, rowing soldiers from their boats and encampments. I quote here from The Battle of Brooklyn, by the late John J. Gallagher, the go-to book on the battle, the book you ought to be carrying with you for the next week or so: “I spied as I peeped out the Bay something resembling a wood of pine trees trimmed. In about ten minutes the whole bay was full of shipping as ever it could be… I thought all of London was afloat.”

There are two things to consider here. First, the sight itself, which must have been awe-inspiring, not to mention terrifying. Second, the masts. The masts were made from tall trees. By this time in their history, the British landscape had lost most of its trees tall enough to be masts. British ship builders were known to take trees from Northern Europe and patch them together. Or they would use trees from New England. Throughout New England, colonists would come upon tall trees, in hopes of harvesting them, but they were often marked as reserved for the king. Now, in New York Harbor, a forest had sailed in. Meanwhile, as Washington reluctantly moved regiments over to the hill country of Brooklyn, New England soldiers were getting views of the British fleet, “a wood of pine trees trimmed.” What percentage of the masts were cut from New England? If a General John Sullivan of New Hampshire looked through his spy glass at a waterborne forest of former New Hampshire forest did that make him that much angrier?

Previously: The Landing In New York and Scouting Old Locations

Robert Sullivan is the author of a several books, including Rats, How Not To Get Rich, and the Meadowlands. His newest book My American Revolution will be published out Sept. 4 and is available for preorder. Top image is a detail from the cover of Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose.