The British Invasion... Again: The Mystery Of The Missing Marylanders' Grave

The British Invasion… Again: The Mystery Of The Missing Marylanders’ Grave

by Robert Sullivan

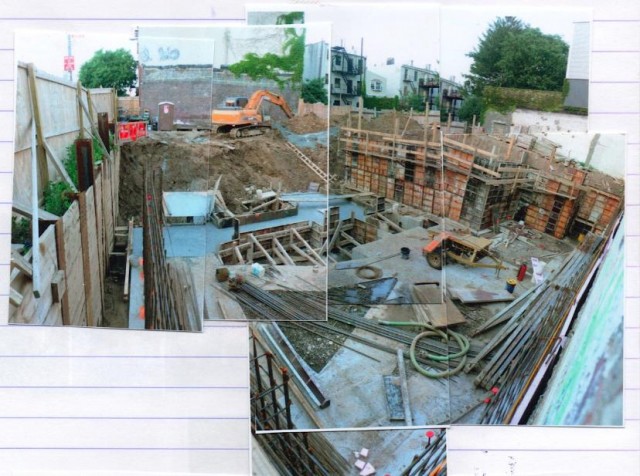

Day five in a series exploring how the trail of the Battle of Brooklyn would pass across modern-day New York. Shown in photo, a potential burial site of the Maryland regiment, near the intersection of 3rd Avenue and 8th Street, that went uninvestigated when it was recently dug up.

The day after the battle, there are dead and wounded all around: 1,000 American soldiers in the woods and the fields all around what is today Park Slope and Greenwood Cemetery, all along the Shore Road that is today in the vicinity of 3rd Avenue and 3rd Street, as well as Pep Boys, Hotel Le Bleu and J.J. Byrne Park. A thousand men were captured. The late John J. Gallagher, the military historian and forensic historian (who is buried on Greenwood Cemetery’s Battle Hill, in view of the harbor and all the field of battle) wrote: “Scattered parties of the living were still hiding in the forests and swamps or trying to make their way to the inner lines around Brooklyn Heights.”

The day before had been a hot summer day, but now there was a summer rain, with lightning and thunder — a storm, that kept the British from sailing up the East River. The British position, after the previous day’s fight, is the opposite of gentrification: the British now control all of the land to the east of Brooklyn, threatening the Manhattan-convenient Brooklyn Heights, where the Americans are held up in their forts and camps. A Rhode Island soldier wrote: “After we got into our fort there came a dreadful rain heavy storm with thunder and lightning, and the rain fell in such torrents that the water was soon ankle deep in the fort.” It was a typical summer rainstorm, much like the rainstorm that was reenacted in Brooklyn this morning, 236 years later.

The big casualties were at what was known as the Old Stone House. The British, under General Cornwallis, were stopped from their advance toward Brooklyn Heights by an American general, Lord Sterling. (His title was disputed in England but Washington, perhaps due to an acute need for experienced military commanders, did not mind calling him Lord.) With a group of about 250 soldiers from Maryland, they attacked the overwhelming number of British soldiers — attacked six times, each time, scores falling dead. George Washington, while watching from what is today Trader Joe’s, is attributed with saying: “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose!” Cornwallis later said, “General Sterling fought like a wolf.”

The Marylanders were reportedly buried by the British in a mass grave, and the whereabouts of that grave have long been of great interest to local Brooklyn historians. But it’s not an interest widely shared elsewhere, despite the valor of the Maryland troops having allowed the rest of Washington’s army to escape. Gallagher was occasionally in search of the grave, at the time I spoke to him about it, at a book signing in 2000, when he signed a book for my then 11-year-old son, ancient history.

Every year there is a memorial service, a small group of people coming to Brooklyn from Maryland, as well as Pennsylvania and Delaware. The American Legion post at 9th Street and 9th Avenue has a plaque. But still, the Marylanders feel forgotten.

To imagine where they were it is necessary to picture the Gowanus not as a canal but as a marsh, with famously large oysters. There was a millpond, where water collected to power a mill. There was a tidal aspect, as there is today. To imagine where the Marylanders might be buried, you have to try and picture where the filled in creek ends and where the land on an old Dutch farm would have begun, a difficult task. Traditionally, it is thought to have been along 3rd Avenue, near 9th Street. There was a plaque for many years. In 1957, James Kelly, the borough historian of Brooklyn at the time, got the federal government to do a dig along 3rd Avenue, near 8th Street, in the vicinity of the traditional burial site. It was a dream come true for Kelly. “No place is more sacred in America,” he wrote. He was with the archaeologists during the dig, when they found nothing, with the exception of old clay pipes and foot-long oyster shells. Recently, an historian was in the Times saying that there should be a dig a few yards away. “The evidence is quite strong,” he told the reporter. “I’m confident enough that I tell everyone I know.”

I know how he feels. A couple of years ago, when a building went up a few dozen feet away, construction crews began to dig a large pit — it was, I realized when I passed it, in the same general vicinity as the traditional Marylanders burial site. I called every archaeologist I knew. Nobody was interested. The hole got deeper. I looked for signs — of what I knew not. I called more people. I took photos. At last, construction began, the hole filled. It was depressing, to say the least, as it is now, when I think of it. I always wonder if there are ghosts in the underground parking lot.

Previously: The Landing In New York, Scouting Old Locations, The General And The Moose and The Battle Begins

Robert Sullivan is the author of a several books, including Rats, How Not To Get Rich, and the Meadowlands. His newest book My American Revolution will be published Sept. 4 and is available for preorder.