How Much More Do Televisions Cost Today?

Sometime between July and September of this year, you may have heard that America’s poor are not really all that poor. Something like this bit of wisdom from Heritage Foundation researcher Robert Rector from July 27, 2011:

How poor are America’s poor? The typical poor family has at least two color TVs, a VCR and a DVD player. A third have a widescreen, plasma or LCD TV. And the typical poor family with children has a video game system such as Xbox or PlayStation.

My goodness, that almost makes you wish you were America’s poor, doesn’t it? (Or maybe you already are — congratulations!)

The implied redefinition of ‘poverty’ as ‘abject poverty’ is certainly a conversation starter, so let’s continue the conversation by looking into how much television sets have cost as the decades (decades with differing percentages of poor people) roll past. As we’ve been looking into how much things cost and when they cost it, we’ve been seeing a general trend of inflation above and beyond the increases in the cost of living. Let’s see if this is also the case with television sets.

***

Though we take television for granted, entertainment was not always so seamlessly obtained. By the 1930s we had achieved moving pictures, but we were forced to watch them outside of our homes, with other people. But the research that would eventually reach ubiquity was already in progress, all across the globe. In the United States, a young inventor named Philo T. Farnsworth was at the forefront. In fact, the first public demonstration of his device, the first all-electronic television mechanism, shooting electrons back and forth onto a screen, creating the moving image viewed, in 1934.

It was only a few short years before televisions were manufactured commercially in the United States. Programming began at the same time, but sporadically and locally, so the earliest owners of TVs were like the earliest owners of compact disc players: sitting on a space-age gizmo that could play the only four CDs available. Eventually, production of TV sets was curtailed in 1942 by the War Production Board, to free up resources for the great effort which ultimately won World War Two (our half of it, at least). Before suspension of TV manufacturing, only 7,000 sets were made, insane luxury items that were more conversation pieces than portals into the world of broadcasting, so they were priced like crocodile handbags — the first RCA model debuted at $600 in 1939. Adjusted for inflation (i.e., converting the purchasing power of six hundred 1930 dollars into 2011 dollars), that would be $9,773.

Gathering data on this topic turned out to be not as difficult as I anticipated thanks largely to the exhaustive website TVHistory.tv, which is the work of a fellow named Tom Genova. The site breaks down everything about television — the technology, the networks, the marketing, ephemera — by era and by year. If you want to, grab a few dazzling bits of trivia so that you may win the next dinner party. (First TV remote control? Zenith Flash-Matic, 1955. Was there ever a pre-cable channel one? Yes, until 1946, when the FCC reassigned the frequency.) Mr. Genova’s site is the place to go. And hidden in there is even this page, which is a convenient chart listing how much television sets cost over time. Boom.

However, the problem with comparing the costs of television sets over time is that the thing that we think of as a “television set” has mutated over the generations. Even in the past decade, think of how the cathode ray tube sets have become extinct. Is it fair to compare the cost of 12” console television from 1948, with a Mahogany cabinet designed to centerpiece a room, able only to receive local programming during limited hours (like, say, a Stromberg-Carlson, retailing at $985 installed — or $9,524 adjusted), against a 25” console from 1986, which was designed less as furniture and more as appliance, able to access the hundred or so national cable networks in addition to the various local stations, round the clock (like, say, a Sylvania, retailing at $540 — or $1,115 adjusted)?

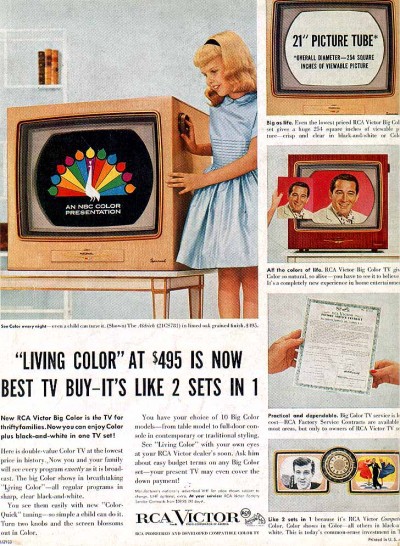

Remember also that the true-life color TVs we are so accustomed to took some time to materialize. Arguably, the first compatible (i.e., could receive shows broadcast either in black-and-white or color) electronic color TV set was the RCA CT-100, a 12½” console, which sold for $1,000 in 1953 (or $8,480 adjusted)? And even into the ’60s, when you could buy a ’68 Admiral 23” color console for $349 ($2,270 adjusted), the black-and-white television was not uncommon, maybe at Grandma’s house. It wasn’t until the late 70s (when you could get a ’77 Sylvania 25” color console for $530, or $1,840 adjusted) that production of B&W; TVs was halted.

What about the introduction of complimentary technologies, such as VCRs, which enabled the viewer to not be present for broadcasts, and duplicate programming for re-viewing? Or of the DVD, which took the marketing appeal of the videocassette and introduced near-theater level quality (which happened, incidentally, in 1996, when a Samsung 10” tabletop would set you back $340, or $490 adjusted)? There are a dizzying array of factors that make it almost arbitrary to try to compare these TV sets to one another, starting with the technology and the available programming, including the fact that the variation of prices within a specific time, from the high-end to the low-end product, can be pretty wide, and ending with the evolving relationship that the American family developed with the “idiot box,” during which it went from luxury to novelty to babysitter to omnipresence. Remember how you didn’t have a TV back in the ’90s because you spent your entire childhood soaking in the CRT goodness and wanted to have your own tiny rebellion? Well, you probably didn’t have a rotary phone, either, but you weren’t moved to explain that to people.

Is it fair to compare? Probably not. But we’re answering the call of the Heritage Foundation premise that TV sets are a negative signifier of poverty, so we soldier on. By the way, a TV right now, in the twilight of television’s dominance as a stand-alone industry, as content increasingly becomes platform neutral? J&R;’s will sell me a Viewsonic 27” LCD HDTV flatscreen for $319. That’s a pretty good deal.

***

Let’s stop talking about television sets and talk about poverty for a second, as that is the issue underlying the Heritage Foundation premise. The U.S. Census Bureau is the organization that set the “threshold” for determining poverty — what is commonly referred to as the poverty line. We all know what it means. It’s a number, and if a person’s annual income falls below that number, then this person is officially impoverished for statistical purposes. These thresholds, however, have little to do with whether this person will receive assistance from the government. Those guidelines are put out by the Department of Health and Human Services. They use discretely different analytical techniques to arrive at their figures, which do vary from the USCB threshold, though not by an awful lot.

Basically how it works is this, a statistician in the 1960s working for the Social Security Administration, Mollie Orshansky, developed a sort of a formula to determine what poverty is. The cost of living is determined, pegged to the cost of a “nutritionally adequate diet,” and then numbered up into a fixed proportion of income of a person/family. This figure is adjusted each successive year based on how the Consumer Price Index changes from the year previous.

The Merriam-Webster definition of the word is, “the state of one who lacks a usual or socially acceptable amount of money or material possessions.” Of course, dictionary definitions may vary, but the concept is relative to the standards set by the rest of society.

So is the standard by which poverty is measured open to question? Of course. As federally determined, it’s based on a 40-year-old theory, so assumedly it would be weighted to reflect concern relevant to the time. Perhaps some aspect of the cost of living is overemphasized, and some other aspect is not given enough credence. Perhaps television ownership should somehow be mixed in there, to keep the process of government assistance honest.

For the record, the current HHS Poverty Guidelines are $10,890 of annual income for a single person, and $14,710 for a couple.

***

So we have the prices of a lot of television sets since their inception, and we’ve converted them to current price levels. They are as follows:

1939: $9,773

1948: $9,524

1953: $8,480

1968: $2,270

1977: $1,840

1986: $1,115

1996: $490

2011: $319

As you can plainly see, if you were graphing that, it would make a line that you could ski down. From 1939 to now, there’s a decrease of a little more than 96%. The cost of acquiring a television has absolutely plummeted.

I mentioned at the beginning of this piece the bit of research from the Heritage Foundation that launched this discussion. It’s hard not to have noticed it, because since the original Backgrounder published on July 19, they’ve wasted no opportunity to restate their premise, including another Backgrounder released on September 13, 2011, practically identical to the July 19 Backgrounder, to respond to the annual Census Bureau poverty report (which stated that the poverty rate was up to 11.7%, or 9.2 million American families). Obviously the Heritage Foundation is a think tank that is committed to communicating their message, to give official-sounding ammunition to like-minded politicians and pundits, but why are they so dead-set on viewing American poverty through rose-colored glasses? They are attempting to set the stage for the argument that less discretionary spending should be spent on the poor (because they have TV sets).

From the initial July 19 Backgrounder:

In discussions about poverty, however, misunderstanding and exaggeration are commonplace. Over the long term, exaggeration has the potential to promote a substantial misallocation of limited resources for a government that is facing massive future deficits. In addition, exaggeration and misinformation obscure the nature, extent, and causes of real material deprivation, thereby hampering the development of well-targeted, effective programs to reduce the problem. Poverty is an issue of serious social concern, and accurate information about that problem is always essential in crafting public policy.

The Heritage Foundation, in an effort to tighten government spending so that less revenue (i.e., taxes) is needed, argues that the poor aren’t really all that poor, and as long as they have a TV set (or an air conditioner, or a PS3) should have no assistance.

Now, they do acknowledge the fact that buying a TV is not as prohibitive as it might have been once. From the September Backgrounder:

Liberals use the declining relative prices of many amenities to argue that it is no big deal that poor households have air conditioning, computers, cable TV, and wide-screen TV. They contend, polemically, that even though most poor families may have a house full of modern conveniences, the average poor family still suffers from substantial deprivation in basic needs, such as food and housing. In reality, this is just not true.

Sidestepping the polemics, while researching this it was heartening to discover an item that has declined in adjusted price for once. But to propose that families below the shockingly low poverty line should either be disqualified by reason of TV ownership, or I guess live a life without a television, or an air conditioner, etc., before the social safety net kicks in, is, for lack of a better word, mean. This is poverty that we’re talking about, a relative level of living standards, not destitution. Better for the Heritage Foundation to come out and say what it means, that it believes that the well-being of its citizens is not the obligation of the government, instead of trying to shame 9.2 million families because they watch “So You Think You Can Dance” once a week.

Brent Cox is all over the Internet.

Ads courtesy of TVHistory.tv, used with permission.