How Much More Does A Steak Dinner Cost Today?

How Much More Does A Steak Dinner Cost Today?

“Marlene Dietrich once said that if she heard an American man rave about a meal, she knew he must have eaten a steak,” says A Treasury of Great Recipes. Published in 1965, the book was written by Vincent and Mary Price (yes, that Vincent Price, or that one, maybe you remember). Price drops the quote in a section on great New York restaurants. And it’s not just the American men who thought this (though more on that below): restaurant critic Ruth Reichl in a 1994 steakhouse round-up wrote, “But there is one thing I have no doubt about: steak is a New York tradition, and when I go out to eat meat, I like to be reminded of that.” At Marlene, Vincent and Ruth’s behest, let’s talk about the steak dinner — specifically, the steak dinner in New York.

So it’s 1956. It’s not really 1956 of course, but we’re pretending. It’s 1956 and you’re flush — the raise came through and it was substantial, or you finally landed the office next to the corner office — so you and the boys from work are going out for a big old steak. (And you are a male. Weird to have to make that distinction, but the exigencies of history demand, in this context.) A sirloin. A salad, and maybe some shrimp cocktail. What’s the bill going to be? How much did you take out of the bank (as ATMs were but a dream, and credit cards were the province of a different class of people, at the time)?

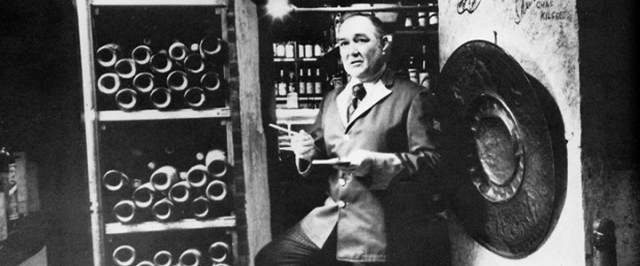

You’re going to Jack & Charlie’s “21” on West 52nd Street in New York City, which is the name that the 21 Club then went by. You start with some steamers, at $2, and an onion soup gratinee, at an even dollar, and then dig into Broiled Sirloin Steak Flamande with Noodles, for $4.50. “21” still has that speakeasy vibe — mostly men, maybe the non-wife women that accompany them, and you just set yourself back $7.50 (which would be $62.56 in 2011 dollars).

Now it’s now again. The VC deal finally closed, or it’s bonus time in the portions of Wall Street not occupied. Off to the 21 Club, which is still there on 52nd, still with the jockey statuary arrayed on the balcony over the entrance. Dinner is prix fixe now, so when you choose to start with the Ahi Tuna Tartare (coconut, lime, hearts of palm, Thai chilies and taro root chips) and the 21 Day Dry Aged Sirloin (with Yukon and purple potato gratin with blue cheese, sautéed tri color carrots and red wine reduction and a desert (which will have to be the equivalent of the onion soup you had 55 years ago), the bill will be $73.

Is that roughly ten-dollar difference significant? Have our steak dinners inflated at the same rate as, say, our candy? Or is it an aberration, and the steak dinner sector of the “delicious things” industry safe from economic pressures?

Let’s not think of the steak dinner as the timeless badge of the spendy meal, the reward dinner. True that it has become that in recent memory — in elementary school, the reward dinner for the Cox children was a trip to Ponderosa, and I don’t think that’s out of character for the day and age — but a long time ago, when men wore hats, the unadorned steak was the province of the chophouse and not the white-tablecloth establishments that were gaining traction. See, for example, the beefsteaks memorialized by Joseph Mitchell, where manly men would spend an entire night grazing on cuts of meat dropped on communal tables, washing it down with oysters and beer. It’s no accident that that certain historic steakhouses seem to be cut from the same cloth as speakeasies (or were, as was the case with the 21 Club, formerly ones).

Early 20th-century restaurant chain Longchamps, was not a virtual men’s club, as were famous NY eateries like Lüchow’s and Toots Shor’s. It was a more refined sort of place, known for its Art Deco style (and popular with the ladies who lunch, who were not generally present in the chop houses of the time). But they did offer a steak to the hungry: in 1938, a Sizzling Sirloin Platter was $1.95. And if you start off with a Fresh Crab Meat Cocktail and a Fresh Endive Salad with Roquefort Cheese Dressing at $.65 apiece, and you’ve got a bill of $3.25 before dashing off to a night at the Bijou (or $52.30, in 2011 dollars).

These steaks come from cows, large contiguous swaths of cows, broken down into table- to single-serving portions, so it’s tempting to look at whether or not the price of a cow has gone up or down in similar ways. We will resist that. Dining is an experience that has to do with so much more than the cost of ingredients, labor, real estate, etc. Certainly fluctuations of the mass production of cows-for-eating affects the cost to the end-user (cf. this

McRib inquiry), but we are speaking more generally of that experience of that peculiar niche of culture that is restaurant dining, with others, in public, attended to in a fashion that is not usually the fabric of the daily life.

One of the difficulties of researching this is that old menus are not exactly easy to find. There are some scattered on the Internet, but should you insist on looking for a specific restaurant in a specific year, your chances plunge. But A Treasury of Great Recipes, which we discussed earlier? It’s a big book, definitely Treasury-sized, with full-page full color photos, raised bands on the spine, a sober gilt design on the cover and a ribbon stitched into the binding with which to mark your place. And in addition to the amiably florid, ascot-wearing descriptions of the jet-setting of the Prices, and name-dropping anecdotes such as the Marlene Dietrich quote above, the book reproduces the menus of the restaurants that contributed recipes. And as it was published in 1965, we have a resource (as well as an awesome conversation piece any kitchen would be lucky to have on its bookshelf).

So from this tome we know that Sardi’s, before it became more widely known for anachronistic Broadway kitsch, had an Alaska King Crab Cocktail for $1.75, a Spinach Salad with Bacon for $1.25, and Roast Prime Ribs of Beef Au Jus with Baked Idaho Potato for $4.85. (Also, the Sauce Maison was 25¢ per person.) And across the East River, downtown Brooklyn’s landmark Gage & Tollner was more of a straight-up chophouse, where the meats were coal-grilled and the waiters wore service emblems denoting years of service. A Crabmeat Cocktail was $1.90, a cup of Green Turtle Soup was $.75, and the Sirloin Steak was $6.00 (or $11.00 for two). In 2011 dollars, Sardi’s cost $58.34 (with Sauce Maison), and Gage & Tollner $62.30

The transformation of steak and potatoes from trenchermen’s delight into fine dining is relatively recent. I spoke to John Mariani, food columnist for Esquire and Bloomberg News and author of numerous books, for insight. According to Mariani, the shift happened in the mid-1970s. “Before that, the model, the paradigm, was the steak houses on and around Second Avenue in New York, such as The Palm and Christ Cella. These were not rough, tough places, but rakish places, populated almost solely by newspapermen.” Mariani tells of the first time his editor at the time, Clay Felker, took him to The Palm in the early ’70s. “I thought I entered into a world, a very masculine world, where quite literally you couldn’t get into unless you knew somebody.” But then a new generation of restaurateurs began opening steakhouses, such as Alan Stillman. Stillman was already in the restaurant business, having opened (and eventually selling) T.G.I. Friday’s, often credited as the first singles bar. He founded Smith & Wollensky in 1977 on the corner of 49th and Third, which had the affectation of the classic chophouse but with modern flourishes, such as attention to the wine list. “The only way to distinguish yourself from those New York steakhouses was to become a little bit more refined,” says Mariani, which is what Smith & Wollensky, and similar places starting at the time, did, and all of a sudden we had a crop of steak joints to which men would take their wives and kids. Not quite haute cuisine, but approaching it. And not coincidentally, the men-only (or the men-and-their-molls-only) fog began to dissipate — as evidenced by Reichl’s sentiments years later.

So, thanks to the December 18, 1978 issue of New York Magazine, let’s see how much this new generation of steakhouses were charging. Sparks, recently having moved uptown to challenge Steak Row, was asking for $14.95 for the boneless sirloin broiled with lemon pepper, $.75 for hash browns and $1 for the salad, while The Palm charged $14 for the sirloin, $2.50 for the hash browns and $2 for the salad. As a price war was raging, initiated by Sparks’ move, we’ll use The Palm for purposes of comparison, which converts to $64.38 in 2011 dollars.

And from the Ruth Reichl story, which is a true mash note to the steakhouses of note, she lists the prices of ten steakhouses from 1994. Sadly, only from one does she include the prices of sides: Christ Cella, a venerable and now-gone Steak Row stalwart: $29.95 for a New York sirloin, $19 for shrimp cocktail and $9.75 for hash browns. That’s a 2011 total of $89.87.

And for another current example, perhaps more traditional steakhouse than 21, let’s visit the Palm again where we will, as Sam Sifton recommends, “Just ask for the steak after some Gigis and a crab.” The East Coast Gigi salad is $15.50, the crabmeat cocktail $19.90 and the Prime Porterhouse $58.00, for a total of $94.40.

Where does this leave us? (And please note that the omission of any steakhouse, historical or current, is not intended as a slight — I’m noticing that my two favorites, Peter Luger and The Strip House, are not included, so there’s that.) The rundown:

Longchamps (1938): $52.30

Jack & Charlie’s “21” (1956): $62.56

Sardi’s (1965): $58.34

Gage & Tollner (1965): $62.30

The Palm (1978): $64.38

Christ Cella (1994): $89.87

The 21 Club (2011): $73.00

The Palm (2011): $94.40

I was tempted, early in this examination of relative prices, to think that the steak dinner was impervious to the forces of inflation, that they could be thought of as a standard unit that keeps pace with increases in the cost of living, even a unit that could be extrapolated as a certain portion of a week’s wages. The data does not support this. In fact, between 1938 and now (referring to the Palm — it’s difficult to trust a prix fixe for these purposes), we’re looking at an (unscientific) increase of 57% — pretty steep. Though also note that the increase really gathers steam in the past twenty years, and that before that, the price was holding relatively steady for forty years.

Of course, as we learned from John Mariani, the steak dinner has changed. Maybe the broadening of the appeal of the steak dinner away from the exclusive province of sawdust and testosterone has enabled the purveyors of steak dinners to seek a more attractive profit margin. Or maybe this is a trend in restaurants in general. Or in life. But yes, your steak dinner costs more than your parents’ at your age, and more again than for your grandparents before them.

And you may be tempted, after reading this, to rush to your closest chophouse for a traditional meal, despite the encroaching expense. In took about three archival menus to render me famished. But remember that the prices quoted do not include tax or tip (or, heaven forfend, adult beverages), so prepare for sticker shock at the end of the evening. Perhaps better to hit the butcher and make a night at home of it.

Brent Cox is all over the Internet.

Historic “21” photo courtesy of 21 Club; Palm photo by Jmichcock, via Wikimedia Commons.