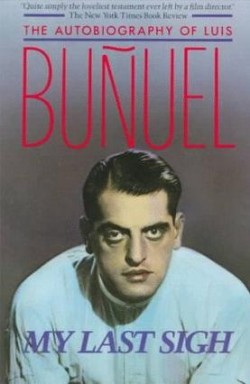

The Autobiography Of Luis Buñuel

by Anthony Paletta

How to sum up a Surrealist’s autobiography? I haven’t the slightest idea. Luis Buñuel’s just-republished My Last Sigh contains, as you might expect, few concrete explanations of anything, but countless provisional manifestoes, an index of cinematic inspirations of bewildering range, more anecdotes than any human has a right to own (he narrowly missed that orgy organized by Charlie Chaplin, but did dismantle a Christmas tree at another party attended by Chaplin — other guests were not amused), and a surprisingly elegiac tone of melancholy. This provides a partial overview, but what else? There’s the family’s pet, an “enormous rat” that accompanied them on trips in a birdcage. This was presumably toted by a servant, as the only thing his father, a “man of rank” would carry in the street was “an elegantly wrapped jar of caviar.” Or, while discussing a budding awareness of sex, the note that a friend “tried to experiment with a mare, but succeeded only in falling off the ladder.” And that’s just before age 10. It is, in any case, a riveting wander in and around Surrealism, cinema and the twentieth century itself.

Any thumbnail sketch of Buñuel’s career looks strangely bifurcated, given the span of nearly fifty years that separates his early work around 1930 (Un Chien Andalou L’Age d’Or) and the late masterworks of the 70s (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, The Phantom of Liberty, That Obscure Object of Desire). This of course leaves out countless superb works, but that’s what summaries do. For Buñuel, born in 1900, there was a distinct time before cinema — his peers in age are not Godard or Bergman or Antonioni but Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford, and Jean Renoir. His earliest cinematic experience? A cartoon about “a pig who wore a tricolor sash around his waist and sang.”

As he writes in Last Sigh: “It’s true though, that for the first twenty or thirty years, the cinema was considered more or less the equivalent of the amusement park — good for the common folk, but scarcely an artistic enterprise. No critic thought cinema worth writing about. I remember my mother weeping with despair when, in 1928 or 1929, I announced my intention of making a film. It was as if I’d said: ‘Mother, I want to join the circus and be a clown.’”

***

Buñuel’s village of Calanda, in Aragon, was a sleepy community whose sole product was olive oil. A rigid order of church and family ordered all of life; there, he comments, “the Middle Ages lasted until World War I.” The first automobile appeared in 1919; a purchase of a “liberal” landlord who later scandalized the community when he replaced his blight-stricken vines with American imports. Drums would beat without pause from noon on Good Friday to noon on Holy Saturday. See every complaint from anyone about the “stifling traditionalism” of their childhood since and contextualize accordingly. This upbringing proved the basis, unsurprisingly, for both his savage assaults on religion and order and his strangely affectionate taste for ritual.

Then a move to the comparative metropolis of Saragossa, where sidewalks were sheer mud, bells would toll continuously on death days (continuity!), and the “most exciting newspaper headlines tended towards ‘Woman Faints, Felled by Fiacre.’” Plenty was still very, very strange. That enormous rat was presumably still scampering around the birdcage. One Holy Tuesday, en route to beat the drums (again, some things never change) Buñuel ran into a “bottle of a cheap and devastating cognac known as matarratas, or rat killer” and proceeded to vomit during mass. Buñuel’s time for Catholic schooling was not long. On to the local public high school, “Reading Darwin’s ‘The Origin of Species’ was so thrilling that I lost what little faith I had left (at the same time that I lost my virginity, which went in a brothel in Saragossa).”

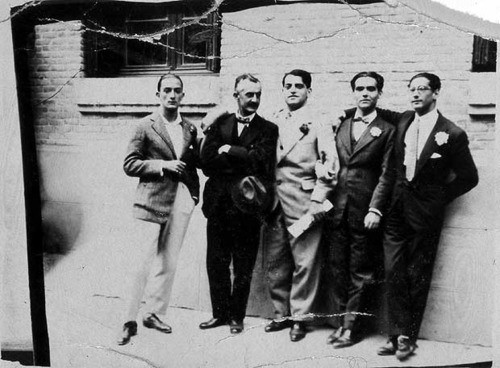

In Madrid, 1926. From left: Salvador Dalí, Moreno Villa, Luis Buñuel, García Lorca, and Jose Antonio Rubio Sacristán. (Via.)

A move to Madrid soon brought Buñuel into the company of García Lorca and Dalí (“we used to call him the ‘Czechoslovakian painter,’ although for the life of me I can’t remember why”). With the change in setting comes a reminder that, as a form, Surrealist autobiographies tend to offer perhaps the highest-voltage company of any kind.

It’s impossible to describe the daily circumstances of our student years — the meetings, the conversations, the work and the walks, the drinking bouts, the brothels, the long evenings at the Residencia. Totally enamored of jazz, I took up the banjo, bought a record player, and laid in a stock of American records. We spent hours listening to them and drinking homemade rum. (Alcohol was strictly taboo on the premises. Even wine was forbidden, under the pretext that it might stain the white tablecloths.) Sometimes we put on plays; even now, I think I could recite Zorrilla’s Don Juan Tenorio by heart. I was responsible for inventing the ritual we called “las mojadures de primavera” or “the watering rites of spring.” which consisted quite simply of pouring a bucket of water over the head of the first person to come along.”

This ritual, he notes, proved an inspiration for Fernando Rey’s drenching of Carole Bouquet in That Obscure Object of Desire.

The question that asserts itself with increasing intensity as the work progresses, and Buñuel moves to Paris is just who he didn’t meet in these years. Spanish dictator Prima de Rivera bought drinks for Buñuel and companions in a bar. Buñuel offered directions to King Alfonso XIII. He led Americans on tours through the Prado. He developed a knack for hypnotizing prostitutes (kicked the habit after one of them died a few months later). He found Picasso personally “selfish and egocentric”) and didn’t care at all for Guernica. While working with director Jean Epstein he was appalled by the whims of Josephine Baker. Epstein noted, “I see surrealistic tendencies in you. If you want my advice you’ll stay away from them.”

***

My Last Sigh (which was written with the assistance of sometime-collaborator and virtuousic screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière) naturally offers countless rambles and diversions. Buñuel loves bars, for one, and accordingly, “the subject of drinks, about which I can pontificate for hours.” His favored drink: red wine. But never drink that in bars. “To provoke, or sustain, a reverie in a bar, you have to drink English gin, especially in the form of the dry martini. To be frank, given the primordial role played in my life by the dry martini, I think I really ought to give it at least a page.” He does just that, not to mention offering his recipe here — as he also does in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.

A product of these gin-soaked reveries? The idea of casting two actresses in the lead role in That Obscure Object of Desire, for a start. And that’s not all on the topic of drink:

After the dry martini comes one of my own modest inventions, the Buñueloni, best drunk before dinner. It’s really a takeoff on the famous Negroni, but instead of mixing Campari, gin, and sweet Cinzano, I substitute Carpano for the Campari. Here again, the gin — in sufficient quantity to ensure its dominance over the other two ingredients — has excellent effects on the imagination. I’ve no idea how or why; I only know that it works.

Inspiration is not built on gin alone, however; there are also dreams.

During sleep, the mind protects itself from the outside world; one is much less sensitive to noise, smell, and light. On the other hand, the mind is bombarded by a veritable barrage of dreams that seem to burst upon it like waves. Billions of images surge up each night, then dissolve almost immediately, enveloping the earth in a blanket of lost dreams. Absolutely everything has imagined during one night by one mind or another, and then forgotten…

These dreams are frequently repetitive and familiar; falling off a cliff, facing an exam for which he’s unprepared, facing an audience for which he’s unprepared. (Even Surrealists, it turn out, have these dreams!) In one, a dead cousin reappears without explanation (reprise in Discreet). A church altar pivots to reveal a secret stairway.

And then his “waking dreams” which are a good deal stranger. He drugs the wife of King Alfonso XIII of Spain and, once she’s fallen asleep, “I slip into her royal couch and accomplish a sensational debauching” (inspiration for Viridiana here — also… uhhhhhh). In another, he gives Hitler an ultimatum to execute “Goering, Goebbels, and the rest of his cohort.” Unseen, he watches Hitler rage at this demand. He assassinates Goering, and then travels to Rome to give Mussolini the same ultimatum. “In between, I slip into the bedroom of some gorgeous woman and sit in an armchair while she slowly removes her clothes.” Of course.

***

The genesis of Un Chien Andalou, the short silent film he made with Dalí in 1929, is probably already familiar; from Buñuel’s vision of a razor blade slicing through an eye and Dali’s of a hand crawling with ants (what, haven’t you ever been involved in a collaborative project before??). Their only constraint, “No idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted.”

Filming was brisk, but, in fact, with Buñuel, it nearly always was; his films play with the imagination with wild abandon but not their budgets; as a practical filmmaker, Buñuel was more of an Eastwood than a Gilliam. “Dalí arrived on the set a few days before the end and spent most of his time pouring wax into the eyes of stuffed donkeys.” Around this time, Buñuel was introduced to the Paris surrealist circle, “at their regular cafe, the Cyrano, on the Place Blanche, where I was introduced to Max Ernst, André Breton, Paul Éluard, Tristan Tzara, René Char, Pierre Unik, Yves Tanguy, Jean Arp, Maxime Alexandre, and Magritte.” Man Ray had already praised Un Chien Andalou to the circle, and the premiere, soon after, attracted Le Corbusier and Jean Cocteau.

What followed was a heady period of determined Surrealism, containing “so many surrealist capers that it’s difficult to decide which to describe.” You can find out about those on your own. “For the first time in my life I’d come into contact with a coherent moral system that, as far as I could tell, had no flaws. It was an aggressive morality based on the complete rejection of all existing moral values.”

The following years involved dizzying shifts in occupation; work for MGM in Hollywood, a job supervising Warner Brothers dubbing in Madrid, tumultuous years during the Spanish Civil War (he advised García Lorca not to go to Granada); a job for the Republican Spanish ambassador in Paris. Work for the Museum of Modern Art in New York arranging Anti-Nazi propaganda (and also editing Riefenstahl prints). A move into Alexander Calder’s apartment; the sight of Leonora Carrington proceeding, during a party, to slip away to take a shower in her clothes and emerge dripping wet. More Warner Brothers dubbing in Hollywood (the note that he suggested the image of a disembodied hand moving through a library in Peter Lorre’s “The Beast With Five Fingers.” And then, in the space of 18 years, making 20 films in Mexico. Diego Rivera taking potshots at passing automobiles (Buñuel, too, loved guns. He relates first facing down bullies at age 14 with a pistol — Surrealists, early enthusiasts for armed deterrence).

And along the way, endless pronouncements.

On the press:

Reading a newspaper is more harrowing than any other experience I know. If I were a dictator I’d limit the press to a single daily paper and a single magazine, and all news would be strictly censored although opinion would remain completely free.

On blind people:

Now, like most deaf people I don’t much like the blind. One day in Mexico City I was struck by the sight of two blind men sitting side by side, one masturbating the other…. Jorge Luis Borges is another blind man I don’t particularly like…. Whenever I think of blind men, I can’t help remembering the words of Benjamin Péret, who was very concerned about whether mortadella sausage was in fact made by the blind. I find this less a question than a statement and containing a profound truth at that. Of course, some might find that relationship between blindness and mortadella somewhat absurd, but for me it’s the quintessential example of surrealist thought.

And what about Surrealism itself?

I’m often asked whatever happened to surrealism in the end. It’s a tough question, but sometimes I say that the movement was successful in its details and a failure in its essentials. Breton, Éluard, and Aragon are among the best French writers in this century; their books have prominent positions on all library shelves. The work of Ernst, Magritte, and Dali is famous, high-priced, and hangs prominently in museums. There’s no doubt that surrealism was a cultural and artistic success; but these were precisely the areas of least importance to most surrealists. Their aim was not to establish a glorious place for themselves in the annals of art and literature, but to change the world, to transform life itself. This was our essential purpose, but one good look around is evidence enough of our failure.

Needless to say, any other outcome was impossible.

Buñuel’s later decades take up, curiously, the least amount of space in the volume, although those, too, are packed with incident and interest. Recall, of course, Marshall McLuhan’s appearance in Annie Hall? Originally a role intended for Buñuel. All of it tremendous fun, but bookended, in this autobiography written, in his 82nd year, by a harrowing grasp of aging, at a point when Buñuel had not been to the movies in four years and stricken by repeat problems of health, was “only happy at home.”

It was in awareness of his own “Last Sigh” that he offered this, on the one thing that really matters: “You have to begin to lose your memory, if only in bits and pieces, to realize that memory is what makes our lives. Life without memory is no life at all, just as an intelligence without the possibility of expression is not really an intelligence…. Without it, we are nothing.”

You might also enjoy: David Bowie’s Forgotten, Campy Berlin Gigolo Movie

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, Metropolis, The Daily Beast, Bookforum, and The Millions on urban policy, historic preservation, cinema, literature, and board wargaming. Previously for The Awl, he’s written about Soviet architecture, the preservation of Brutalism, David Bowie’s campy Berlin gigolo film and the screenplays of Tom Stoppard.