The Sublime Sci-Fi Buildings That Communism Built

by Anthony Paletta

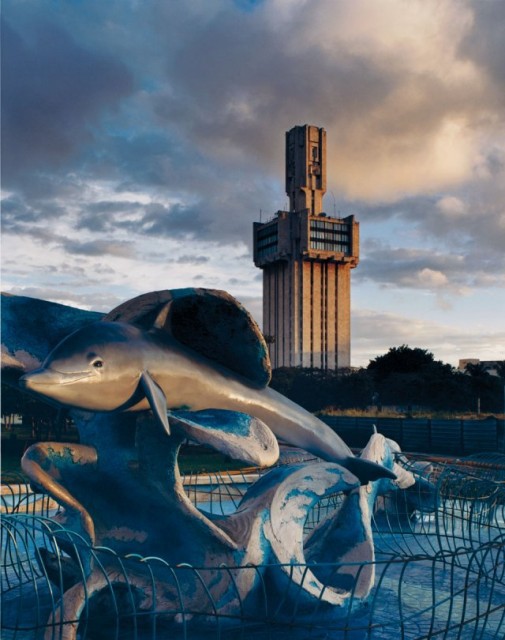

The House of Soviets in Kaliningrad.

Photo by Frédéric Chaubin, from “CCCP: Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed.”

The architecture of the Eastern Bloc — a conundrum of impossible complexity, or at least that’s what it looks like judging from the daily view of my collection of coffee table books. Yes, that’s right, coffee table books. The recent glut of art volumes devoted to Soviet architecture may be surprising to anyone who previously thought “Soviet architecture” had about as much to do with “art” as “Soviet leaders” had to do with “glamour.” Yet here is a whole bookshelf to contradict that view. There’s Taschen’s CCCP: Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed, Hatje Cantz’s Socialist Modernism, Monacelli’s The Lost Vanguard: Russian Modernist Architecture 1922–1932, Roma’s Spomenik (not, in fact, a sequel to Rango) and, the most euphoniously titled of them all, Jovis’s Modernism In-Between: The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia.

These are not your parents’ dour architecture monographs, complete with such entries as “On the problems of developing the center of Kishinev” or “Approaches to using the vernacular in Tashkent and Navoi” (real items from a 70s-era release) but are lavish, glossy, and handsome. One of these volumes was released in 2007, the rest date from within the last two years. What does this all mean? What have we learned from this publishing spree? Well, either quite a lot, or possibly nothing, but bear with me.

The 1975 Soviet film The Irony of Fate, a Russian favorite for Christmas season viewing to this day, boasts a Twelfth Night-like plot that turns on the anodyne similarity of Soviet housing. The narrator opens, mordantly, “In the past when people found themselves in a strange city they felt lost and lonely. Everything around was different: streets and buildings, even life. But now it has changed. A person comes to another city and feels at home there.” In a landscape of bland uniformity, “can you name a city that hasn’t got First Garden Street, Second Suburban Street, Third Factory Street, First Park Street? Second Industrial Street, Third Builders Street?” This similarity in design, not to mention the standardization of furniture and locks, results in our drunken protagonist deposited in the right apartment on “Third Builders Street”, but in the wrong city, and romantic comedy misadventures follow. (In fairness, It’s a Wonderful Life must look like a pretty odd holiday ritual to the average resident of Novosibirsk as well.) In any case, there’s no denying that most Soviet construction was oppressively dull and derivative; in this case, Soviet censors didn’t even seem to bother to try.

Milan Kundera wrote, in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, “in the realm of totalitarian kitsch, all answers are given in advance and preclude any questions.” Questions, as we have seen, such as “am I in the wrong city?” and “are you my wife?” but this is immaterial. Totalitarian kitsch, in the realm of architecture, poses innumerable questions once the core of the totalitarian has passed. Architecture in totalitarian societies unquestionably constitutes an exercise of power; the question stands how effective this exercise remains once that rule has passed, and whether the nature of a given totalitarianism is indissolubly bound up in the stone, concrete, and steel to which it gave form. Some particularly egregious symbols are demolished, but far more often, buildings are simply repurposed and assume some new identity. The Reich Chancellery was demolished, with excellent cause; but the Luftwaffe headquarters now houses the German Finance Ministry. Few today, outside of perhaps any especially melodramatic Greek circles, would think that this amounts to any sort of continuity of purpose.

Some wish to expunge the physical memory of totalitarian rule as fully as possible; others believe in retaining some memory of the humane strivings of these former socialist states, that would design and build a puppet theater, or a “children’s health resort basin” or countless other facilities for public recreation. These debates continue. There are, of course, far more buildings that many would like to see demolished, and this not because of the buildings’ latent symbolic power, but simply because they are godawful monstrosities. But, as you may have heard, money is not something in which the former Eastern bloc is generally much awash, and so they stand.

Up till now, though, we’ve been talking about the miserable mean of Eastern bloc architecture. The picture looks quite different when you shift your attention to the shining peaks of the style. Author Frédéric Chaubin, who wrote the Taschen volume, calls these buildings “aesthetic outsiders in an ocean of gray.” And it becomes far simpler to conclude that, all questions of the historio-political, post-syncretic mediatory, and polythechnic-institutional aside, that this cream of Eastern Bloc construction is simply awesome.

Let’s start with the most otherworldly. As Chaubin notes in his introduction to Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed, “Anyone’s first trip to New York always comes with a feeling of déjà vu, as if one were walking onto the set of a movie seen a hundred times. In contrast, there are vestiges of the Soviet Union that seem like backdrops to movies that never hit the screen, because they were never made.” This, if it seems possible, decidedly understates the visual impact of the architectural legacy of the later decades of the Soviet Union and associated states. Eastern Sci-Fi cinema, as superb as its product and settings often were, clearly neglected the treasures in its own backyard.

The architecture facility at the Polytechnic Institute of Minsk. Photo by Frédéric Chaubin.

The Druzhba sanatorium. Photo by Frédéric Chaubin.

There’s the architecture facility at the Polytechnic Institute of Minsk, a mass whose composition is so kinetic that it’s easy to suspect that its treads are simply below your line of sight. There’s the Druzhba Sanatorium, where hillside columns support a cog-like rounded center, teethed with oversailing balcony pods. The CIA and Turkish Military suspected it to be a rocket launcher; I suspect it to be fun. Or the Ukrainian Institute of Scientific and Technological Research and Development, for which there’s really no description other than it looks like a flying saucer landed square on top of a Kiev building and that the scientists rejoiced in the convenient extra lab space.

The Ukrainian Institute of Scientific and Technological Research and Development. Photo by Frédéric Chaubin.

The Yugoslavian monuments known as “Spomenik” are another incomparable Eastern entry.

Two photos from Jan Kempenaers’ Spomenik.

Created as war monuments, they resemble nothing that you’ve ever seen. Their style, intriguingly, was borne out of the difficulties of commemoration in post-war Yugoslavia. As Jan Kempenaers writes in Spomenik:

In multicultural Yugoslavia… the Second World War was a layered and ambiguous situation. Not only a war of liberation against the aggressor Nazi Germany, but also a civil war with complex oppositions between ethnic population groups who fought one another from different points on the ideological spectrum, such as the Partisans, the Ustase and the Chetniks. For this reason, the war monuments could assume neither a heroic or a patriotic guise. In other words, they had to be neutral enough to be acceptable to both victims and perpetrators. After all, once the slaughter was over, the former opponents had to collectively form the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia together. Hence the choice of a neutral, almost frivolous visual language, whereby the Spomeniks look more like sculptures in an open air museum than the usual war memorials full of military pathos and thundering cannons as were erected at Verdun or Stalingrad.

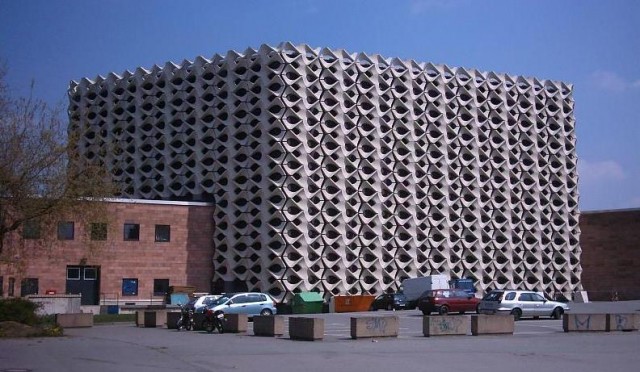

Then there’s the Chemnitz Stadthalle in the former East Germany, which boasts a honeycomb-esque latticework that seems designed for the easy ingress of DDR winged supermen.

The Chemnitz Stadhalle. Photo courtesy of Andreas Praefcke.

I once described the former Georgian Ministry of Highways as most resembling an abandoned game of Jenga, and I still can’t think of any other means to remotely hint at its wonderful frame. Or, turning somewhat back to earth, there’s the Soviet Embassy in Havana, a tropical campanile for the Brezhnev era.

The Soviet embassy in Cuba. Photo by Frédéric Chaubin.

Much earlier construction bears a closer relation to recognized international vernaculars, which is to say that it still often stands at the crisp edge of innovation in the 1920s and 1930s. The early Soviet state recruited from the cream of modernist architects; there’s Le Corbusier’s Centrosoyuz Building in Moscow and Erich Mendelsohn’s Red Banner Textile Factory in St. Petersburg, which are each striking.

The Centrosoyuz Building, in Moscow. Photo by Richard Pare, from The Lost Vanguard.

The Red Banner Textile Factory in St. Petersburg. Photo by Richard Pare.

Even more interesting is a similar realm of domestically designed constructivist architecture such as Ivan Fomin’s NKPS Building, a columnar block given raw energy through a sleek window-banded corner tower. Or the Gosprom building in Kharkov, a majestic multi-tiered wonder balanced vertically by glazed stairwell window columns and horizontally by a series of walkways staggered across intervening streets (also to be found in the decidedly non-sci-fi cinema of Eisenstein’s The General Line).

The Gosprom Building, in Kharkov, Ukraine. Photo by Richard Pare.

Or the Narkomfin building in Moscow, which resembles a more rough-hewn version of Erich Mendelsohn’s Rudolf Mosse Publishing Company building in Berlin, in which a modern-styled turret complete with ribbon windows is balanced by an opposite rounded corner — only without any windows, and giving way three stories from the top of the structure to the rectilinearity of the rest of the building.

Given the sheer size of the former Eastern bloc, it might seem not surprising that the area would have generated at least some architecture of consequence and yet you’ll find notably small sections on the Warsaw Pact or non-affiliated communist states in most architectural atlases or surveys released at a point when C.C.C.P. was more than a Taschen title pun. There’s little question that the planned economy was good at little, and still less, in the aggregate, at architecture, but recent publishing has made clear that it too hit breathtaking heights of experiment and form. No matter which airport you’re in, or how much Stolichnaya you’ve had, you’ll never mistake any of these fantastically distinctive structures for Third Builders Street.

Related: The Ugly-Beauty Of Brutalism

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, Metropolis, The Daily Beast, Bookforum, and The Millions on urban policy, historic preservation, cinema, literature, board wargaming, and comparably brutal topics.