San Francisco's Baffling Jejune Institute Gets A Documentary

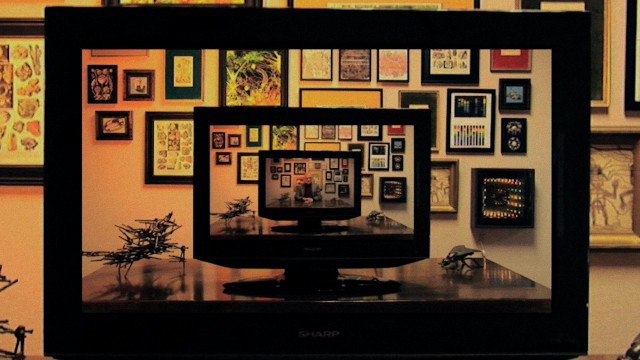

The toughest part of writing about San Francisco’s Jejune Institute “thing” was trying to describe it, something I attempted to do for this site twice. In a first piece about the citywide game, which was put on by a group called Nonchalance, I went with “[p]art public-art installation, part scavenger hunt, part multimedia experiment, part narrative story.” For the follow-up, I added “underground alternate reality game” to the mix. Both summaries missed the mark, partly because of my own inadequacies as a writer, but also a symptom of the project’s sprawling originality — it wasn’t like anything else out there, and that was part of what made it so fantastic. Thankfully, Spencer McCall went ahead and made The Institute, a 90-minute documentary about the project that neatly encapsulates what made this whole whatever-it-was so wonderful.

It premiered last October at the Mill Valley Film Festival, and has been doing the circuit ever since. It showed at Sundance’s hipper little brother Slamdance this January; highlighting the film in his column, Scott Foundas at L.A. Weekly perfectly summed up my feelings about the whole endeavor by admitting that “[r]arely have I felt so absorbed by a movie about people I found so incredibly annoying.”

Last week, I sat down with McCall in an eerily empty mall food court in San Francisco to chat about making the film. A bit of background about how the game started: Creepy cult-like signs scattered throughout SF urged unsuspecting people to head to the skyscraper located at 580 California in the city’s Financial District. From there, you’d head to the 16th floor and ask the receptionist for “the Jejune Institute.” He or she would hand you a key with some instructions printed on it, and down the rabbit hole you’d go.

Rick Paulas: What was your experience with the game before making the film. Were you a player first?

Spencer McCall: No, I wasn’t. I went to the cusp. I checked out 580 California. You know, word of mouth was going around, everybody was saying, “You got to go to 580 California. I can’t tell you what’s there, you just have to go.”

So me and my girlfriend went, did the whole experience in the Financial District building, went into the Induction Room, got the cards, and walked out onto the streets and were like, this is weird. This is just too weird. They’re probably following us right now. What is this? What is this? So we left. We didn’t even do it. And I put it out of my head for a little bit, but it was still there, like, what is this?

Yeah, just what is this thing trying to sell?

Right. I started to browse online to find out what this organization was, and started seeing terms like “alternate reality game” that didn’t mean anything to me. The biggest question to me was, why doesn’t this cost money? What is it marketing? What is it advertising? And no one knew. Absolutely no one knew where the money came from, or what the point of it was.

A little while later, a friend of mine named Gordo was approached by the Jejune people to lead this kind of street protest for them. They met him on the street and asked him to lead a protest, and he just lead this protest through San Francisco without really knowing what it was about. [Gordo’s story is in the film.] A bit after that, I got laid off from my job and was looking for work, and Gordo said these Jejune people might be looking for someone. So I met them, and they wanted to know my story, what I was about, what I was into, and they said we have a couple of promotional videos we need but we can’t tell you how they’ll be used. You just have to sign this NDA and do them. And they paid almost nothing. So that was kind of how I got behind the curtain a bit.

What were the videos?

Some were commercials for the whole experience, a couple were in-game videos like these quasi-false histories of this organization like where these people came from. And after The Seminar [the game’s closing Act/ceremonies], they left me with this hard drive that had about 700 hours of footage on it. Just everyone’s footage. Handheld, archive, security-cam footage of people entering the Induction Room. They hid a lot of cameras. A lot of photos. I was still unemployed at the time, didn’t have too much to do, so I just emailed Jeff and asked, “Do you mind if I start putting something together?” And he said, knock yourself out. Nine months later, I came back to Jeff with a cut.

I did the first two Acts as a player, but then my reporter instincts got the best of me and I started to interview Jeff and company. Which was great, but I was never able to enjoy the game after that point. And watching Act Four take place, I was kind of jealous of the people playing it.

I was too, a little, but not until I had gotten the whole picture of the experience. I’m not going to say they were crazy, but the players were going down this rabbit hole with no idea where it was going to lead. I’d say I’m more skeptical than that. But then, as I learned more about what this project was, and that the whole point of it was letting go of your skepticism, and releasing yourself from the confines of what’s real and what’s not, you could say I was sort of envious.

When is this going to get released?

We have interest right now. We’ve got distribution offers for iTunes, Netflix, online kind of stuff. We have one for theatrical. We don’t want to be cocky or exclusive or anything, we just don’t want to put it online and have it get buried. There’s like a million things on Netflix.

When you say “we,” does that mean [Jejune creator] Jeff Hull is involved?

I use the Royal We to kind of not sound pretentious. Jeff isn’t really involved, and that’s actually more by his design. He doesn’t want it to come off as it being a vanity piece. And I couldn’t agree more. Jeff likes the movie. It takes a couple little jabs at him, but he likes it. So, I guess when I’m saying “we,” I am generally just referring to myself. Doing a Gollum thing there.

When I was writing my articles, I found it pretty difficult to describe this multi-media super-sensory world with just words. So for you, using video, what was the process of telling this story that was hitting you in so many non-video ways?

That’s the thing. It was a story being told through multiple platforms, which was really cool to me. The fact that you could tell a story not just through TV and not just through a book, but all these interactive immersive elements coming together to give you a story. So, in that regard, turning it into a movie is almost sacrilege. That’s killing the experience. But obviously a big part of the experience was confusion and uncertainty and nuance in reality, so I wanted that to be in the movie too.

But, you know, I really just let the players tell their side of it. A lot of times, they were so deep in it they had a very esoteric perspective. It was very much “well, the Hollow Heads knew that Kelvin has intercepted the blah-blah-blah” and I had to keep going back and saying, “Wait, I don’t know what that means. Can you explain that?” So I kept on approaching the movie like I was showing it to somebody’s grandma. Is she going to get this?

When looking back through the Acts, they progress from being a unique but seen-before scavenger hunt thingy in Act One and Act Two, and then Act Four turned into this magical experience…

Act Four is very much like, this is very beautiful, this all feels so warm. But when you do that in a story it needs to be preceded and followed by adventure. It was preceded by it, but when people didn’t get that out of Act Five that was out of a sense of narrative expectations, in a way that a movie at the end of two-thirds gets really sad and everyone’s all bummed out and then you explode shit and everyone’s happy.

Sure, but that’s the difference between a movie like Die Hard and something like 2001, where you have this open-ended weird symbolic last section. Like, Act Five, I hated it initially. It was just an annoying weekend.

99% of people said that.

But looking back on it, it’s really tough… I certainly don’t hate it anymore. But it’s the argument between meta and straight storytelling, right? You can get the same out of both types. It’s just with straight storytelling you have to take the extra step to see that this means that, and this stands for that. But in meta it’s just, “No stupid, this is what it’s all about. This is what I’m telling you about.”

Did you ever see The NeverEnding Story? What’s cool about that is, the people of Fantasia need a human being to give a new name to the Empress. And the only way they can get someone to come to their world is to create a story that someone can immerse themselves in, they can only come to this world and save it if they believe that the story they’re reading is essential and necessary. The story doesn’t matter. It’s just the tool to get you to come together and open up your eyes. It’s not the Holy Grail; it’s the quest for the Holy Grail. But everything that the Holy Grail would give you, you could gather on the quest. So that was the message. And that’s not necessarily a new message. You know, “it’s the journey not the destination.”

Ultimately, then, the documentary is kind of the final draft of Jeff’s project. No one’s going to play the game again, it’s gone. This is what’s ultimately going to exist. When you were making it, did you feel any obligation to preserve something?

No. Not at all. I wasn’t making this to be the preserver of this ancient world. It was just to answer the basic, fundamental question of what story is this telling. Yeah, there is so much peripheral story crap, and links, and the B-Boys being connected to these delta particle drugs that were made by Eva’s father’s friend who went missing and created the polywater, and whatever. It’s like, no. That’s not… again, the story didn’t matter. I cut where it didn’t make sense to me.

What, ultimately, is your final impression of the game in general and what they did?

Which is actually really interesting is that most of the people who participated were, much like myself and much like people in the Bay in general, very secular people. I’m not a religious person, none of the people who participated in this game were. Which isn’t really surprising. But what a lot of these people got was this sense of spirituality, or a sense of something more going on in their reality. And who cares if that’s created by people instead of a magic thing? These people got this sense of congregation, and they came together. It was no mistake that Act Four was in a theological establishment. So that’s what’s really cool to me, is that you can believe in something more going on. You can believe in magic and you don’t have to attribute it to a God or whatever…

… or a corporation, or a movie…

… but at the same time, people love to say they’re spiritual but not religious, and this was definitely religious but not spiritual. Because it was all the tradition and story that religions have, but none of the necessity to believe in any of the magic. And I don’t know if that was really Jeff’s idea. His idea was to get people to stop looking at their phones, to explore the world they live in, not be afraid to go down an alley because they think it might be owned by someone. You know, don’t go robbing anybody, but explore it. It’s your city, too. That would be Jeff’s thing.

Mine would be just to question the media you’re presented with. I think a movie has the ability to make you open your eyes and linger and bounce around in your brain for awhile, but don’t take it too seriously. And if you do, be sure you really question it and get the answers. It’s like Jaws. If you’d seen the shark in the beginning, would it be that sharp or spooky of a movie? Probably not. You know at the end they do show the shark. I don’t think I ever showed the shark in this movie. But that’s the idea. Go find the shark yourself. You decide.

Previously: Last Chance: The Mysteries Of San Francisco’s Creepy Jejune Institute and The Perplexing Final Chapter Of San Francisco’s Jejune Institute

Rick Paulas is an Institute graduate.