Last Chance: The Mysteries of San Francisco's Creepy Jejune Institute

There was a slight chance we were being indoctrinated into a cult.

The night before, during a tough trivia night at the Pig and Whistle, my friend Michelle had scribbled a name and address on a cocktail napkin. “Go to 580 California Street, head up to the 16th floor and ask for the Jejune Institute.”1

“What is it?” I asked.

“I can’t tell you anything but that. Trust me, you’ll like it.” She saw me wavering. “It’ll take fifteen minutes. If you want to stop after that, you don’t have to do anything else.” And so with a few hours to kill on a rainy Saturday, my girlfriend and I went.

Which is how we found ourselves in this small office in a high-rise overlooking San Francisco’s Financial District. One wall was covered with framed photos, plaques, maps and artwork. Obscure scientific journals and odd trinkets sat on the shelves. An older man who looked extraordinarily like Terence Stamp in The Limey, minus the insane Rottweiler look, addressed us from the television. Broadcasting from a secret remote location, he explained the Institute’s role in “socio-engineering” and how various devices like telepathy and the bending of the time-space continuum will help mankind. (Think DHARMA from Lost.2) He told us to turn to our right, reach into the table drawer, and sign the consent form we’d find there.

“Do not read the initiation form,” warned the man. “I repeat: Do not read the initiation. If you do read the initiation, then do not tell anyone what it says. And do not follow the instructions.”

“What the fuck are we doing?” asked my girlfriend.

Following the instructions on that form, was what we were doing.

MASSIVELY IMPORTANT SPOILER WARNING: This is where, if you’re into puzzles, games, cults, scavenger hunts, multi-media entities or anything reminiscent — and you live or are vacationing in the greater San Francisco area in the next month (that is, before April 10th!) — you should follow the advice of my friend Michelle and just go without asking any more questions. Reading the rest of this will, ultimately, ruin it.

The directions that the man had so sternly told us to ignore led us on a wild afternoon: ducking past security guards, prowling down alleys, pushing aside metal lock boxes looking for codes, locating hidden bricks on ancient churches, peering over the balconies of private businesses and cracking passwords to listen to secret voicemails.

It was a game, but it was something more than that, too. It was a game of Nonchalance. Part public-art installation, part scavenger hunt, part multimedia experiment, part narrative story — yet even taken together, these terms don’t describe the project fully.

After my experience playing the game, I spent a few weeks obsessing about it before contacting Jeff Hull, the project’s creator. “What’s your take on this?” he asked. “Magazines have had a tough time trying to get a handle on what this is.”

A few inches north of six feet, Hull has a shaved head and soft melodic voice. He began his foray into multimedia projects a decade ago with the group Oaklandish, an artist-collective that specializes in outdoor film screenings, public art exhibitions and urban capture-the-flag games. “I had always been theorizing about narrative across media in an immersive way. In 2008, the opportunities presented themselves to produce this.”

The question is, just what is ‘this’ anyway?

Hull initially conceived of creating a simple multimedia art project. “There was this trail by my house I’d take my dog for a walk. The idea was [that participants] would gather there, tune into a radio broadcast that would walk them up the river and tell this story along the way. The experience would take a half hour total.” But some projects have a life of their own. “The universe just expanded. It became so much deeper than we initially conceived.” Turns out, he was producing an alternate reality game. “I didn’t even know what an ARG was at the time,” said Hull. “We were totally ignorant of it.”

An ARG is an interactive multi-media game that utilizes a combination of new-school tech (websites, emails, videos) and old school (live actors, flyers, sidewalk graffiti) to create a narrative for players to participate in. When I told a friend about Nonchalance, he said it reminded him of the David Fincher movie The Game. While Nonchalance’s wasn’t nearly as elaborate as the one found in that film — not once while I was playing did I have to break out of an open grave in Mexico, for example3 — it’s a pretty good illustration of how an ARG works.4

My first experience with an ARG came in 2001 after reading a post on a message board encouraging people to closely examine the poster for the new Spielberg film A.I..5 In the credit sea of producers and writers was one for Jeanine Salla, who was listed as the film’s “Sentient Machine Therapist.” A quick Internet search led to a string of fictional websites that unspooled the story of a murder that took place in the year 2142. Players who entered their contact information almost immediately began receiving emails and phone messages from the game’s characters containing clues to solve the mystery. The game was quickly dubbed “The Beast” by participants.6 But there were problems.

First, it was tough to emotionally connect to a project that was put together by the bottom-line hungry Hollywood machine.7 It ruins some of the fun when you feel more like a consumer than a participant. Another problem was The Beast’s nationwide scope. It only made sense that the studio wanted to attract as wide an audience as possible — this was an advertising campaign, after all — but the Beast’s broad geographic reach made it unable to make use of many real-world settings. A live event in New York would mean leaving out the West Coast and Midwest, etc. As a result, most of the narrative was confined to websites, that is, puzzles that can be solved from office chairs; and unlocking a hidden page on a website isn’t nearly as exciting as creeping down an alley, finding a box and removing it to reveal a password. Worst of all for The Beast was that, due to its attachment to the upcoming A.I. premiere, it arrived with an expiration date. It lasted during the spring and summer months of 2001. After that, anyone coming late to the party had to settle for message-board posts describing how cool that thing they missed was.

By contrast, the Nonchalance experience put together by Hull has a DIY texture to it, every piece of the project designed and, more or less, hand-crafted by Nonchalance or one of Hull’s artist friends. Instead of having the backing of a movie studio, this venture was almost completely self-financed. It also purposefully used well-defined local settings — walkable sections of San Francisco — to more fully blur the lines between reality and game.

And best of all, Nonchalance was built, to use Hull’s term, to be “perpetual.” I could enter the game fourteen months after it was debuted and still have much the same experience as the first person to ask the receptionist on the 16th floor for Jejune, please. Now, however, an end date has been assigned, and after a nearly three-year run it will be no longer after April 10, when the epilogue is completed.

The game was released in a series of Acts, chapters in an ongoing story. Think of it like seasons of The X-Files. (Except without the eventual and inevitable letdown.) If you were watching at home on a week-to-week basis, the end of the season was accompanied with a long and painful wait for the next one to start. In the same way, after Act I was released, players who solved it had to wait patiently for Nonchalance to design and release the second act. And when they solved that, they had to wait once again for Act III.

From the beginning, Hull and company rewarded the game’s earliest adopters and most obsessive players. In between acts, the group produced a series of “mini-episodes.” So, for example, in the interim between Act 1 and II, a handful of gamers were told to meet at a payphone for instructions. After completing the assigned task — dance like crazy on a public sidewalk — they received a map that allowed them to get a headstart on Act II.

The “mini-episode” between Acts II and III took the form of a rally held in San Francisco’s Union Square, put together by the Elsewhere Public Works Agency — one of the game’s fictitious groups — as a way to expose the horrors the Jejune Institute.8 The rally was attended by over 200 people, who witnessed members of the EPWA “scare away” that Terence Stamp-looking dude from the indoctrination video. So, while you can start from the beginning and play almost the entire game in a week’s time — just as you can watch all of The X-Files on Netflix Instant over a week — you won’t have the same experience as that first batch of players.

As the references to EPWA and a rally against a fictitious organization hint at, the point of an ARG like Nonchalance’s isn’t to just give a bunch of random clues that get players from point A to point B. That’s just a scavenger hunt. What makes an ARG different is the narrative layered on top of the clues: there’s a story being told.

In the alternate reality of Nonchalance, the story revolves around the warring of two entities vying for the minds of San Franciscans. There’s the science-heavy — most likely evil — Jejune Institute which may or may not be suppressing and controlling the thoughts of the city’s citizens, and the EPWA, an underground rebel group trying to dismantle Jejune. There’s also Eva Lucien, a mysterious woman who is somehow the link between the two. She went missing in 1988, her last-known appearance near Coit Tower. If my tone sounds hesitant, it’s because this description may not be completely accurate. You try deciphering a story spread across so many different platforms and with so many different characters.9 It’s dizzying.

In addition to Hull, another key figure behind the game was Sara Thacher. If Hull was the dreamer behind the project, Thacher was the one who ensured the dream machine ran properly. “We didn’t even think about beta testing before Sara got involved,” said Hull. Thacher has since moved on to the Go Games, but while she was still with Nonchalance, I accompanied her on a biweekly trip she took through Chinatown to make sure the pieces of the game were still intact.

“The story isn’t as important as the experience of doing it,” she said. “Talking about the project isn’t able to be done. You have to experience it.” She removed a large piece of white chalk from her Ziploc bag and drew the Nonchalance symbol (a slightly tilted rabbit head) on the sidewalk. “This is just to help let people know they’re on the right track.”

Thacher’s background made her a perfect fit for the unique project. A graduate of a local “structured art school,” she realized pretty quickly that she wasn’t into the standard, stuffy-museum path that her art degree was taking her. “The actual person-to-person interactions were the art,” she said. She went on to collect a MFA from the California College of the Arts in a new program called Social Practice, designing projects like “Walking a Mile in Other People’s Shoes” (in which Thacher physically walked a mile in someone else’s shoe before shipping it back, along with a personal letter) and “San Francisco Vacation Surrogate” (in which she toured SF for someone who couldn’t, attending events and visiting sites they wanted to see, and shipping them back letters, ticket stubs, postcards and journal entries describing the trip they could have taken). She got mixed up with Nonchalance after answering a Craigslist ad.

The third core member of the group has been Uriah Findley, who Hull knew from his Oaklandish days. Findley’s specialty is audio and video editing but he also designed most of the actual real-world items found in the game. When I first met him, he was carrying an ‘80s-style boombox that was accented with patchy artistic flourishes before spray-painting the entire thing gold.

While Hull was the lead writer of the Game Bible10, it was this core of three — aided by about 30 different freelance writers, artists and actors — who spent much of 2008 creating the project. But even when the pieces were in place, the hardest part was getting people to walk through the doors of 580 California Street. To do that they had to create “in roads,” bait to attract players. The group posted vague, mysterious flyers around San Francisco, started fictional eBay auctions and utilized a variety of sections on Craigslist to spread the word. “People thought it was a cult,” joked Hull. But soon enough, the people came. After that, it was all word of mouth. In early 2010 the group celebrated the 4,000th person to complete Act I.11

A few weeks after our first conversation, I went with Hull on a Nonchalance venture. We sat in his car, drinking coffee, and waited for Act IV in the game to begin.

In the previous few weeks, eight of the game’s most hardcore players had received a variety of postcards, emails and phone calls from game characters. These communications came embedded with seemingly nonsensical clues. Only when all eight players came together would the clues make sense. The day before, they had been sent the final clue instructing them when and where to meet. Hull motioned to a nearby alley, “They’re going to come out of there… at least, I think they’re going to come out of there.”

At this point, there was still plenty that could go wrong. Someone could have misheard a clue. Or they could have taken a left when they should have taken a right. Or someone might not have shown up, leaving the other seven with incomplete clues. Beta testing can solve only so many problems. So we waited in Hull’s car. And we waited. The silence gave him a moment to reflect on the future, and end, of these games.

See, this whole project, while being a public art installation and all of the other slippery identities contained within that, is also a business development project. Hull is marketing Nonchalance as a media production company with creative services, and these games are a calling card of sorts, a tangible product companies can use to decipher how best to use their services. So far, Nonchalance has completed a handful of client projects, including developing an ARG for Greenpeace and creative consulting for the Oakland International Airport. After the game’s conclusion in April, the group will focus on networking and trying to sell the idea that this, whatever this is, has some value to clients. “We’ve had this ‘If you build it, they will come’ attitude,” said Hull. When I asked him what the group plans to do if they can’t generate the business, he responded immediately, almost instinctively: “We have to.” There’s no other option.

Yet as I sat beside Hull, I could sense some uncertainty about the group’s future. What if all the past work had been for nothing? But then Hull’s eyes widened and he sat up in his chair, suddenly giddy, worries about the future wiped out.

“There they are.”

The first eight participants of Act IV emerged from an alleyway, a little behind schedule but still on course. Hull had once told me the grand mission statement of this project, “The Jejune Institute calls itself the Center for Socio-Reengineering, and that’s something that’s a little bit cheeky, but we’re pretty sincere about that goal. We want to reengineer the way people are interacting with space and with media and with each other. That’s our objective.” That mission was now working.

Eight people — strangers to one another before that day — were on a hunt together. They turned to their right, the wrong direction, basically aiming directly to where we were parked. I ducked in my seat. Then after a brief conference, the group changed course, moving left, the correct direction. They crossed the street and entered a labyrinthine mausoleum12 where the rest of the act would take place.

“My job here is done,” said Hull. His role that day was simply to make sure the eight got into the mausoleum, at which point the overseeing duties would be handed over to Thacher and Findley. Hull wanted to stay out of the players’ sight on the remote chance someone might recognize him, ruining the illusion of the game. Yet, instead of heading home, he idled in the parking lot. “I think there’s a spot on the second floor we can look down from.”

He turned off his car and we jogged up to the mausoleum’s second floor.13 “I have to hide from Sara,” he said. “She’d kill me if she knew I was in here.” From our perch we watched the eight perform the duties exactly as assigned. Hull watched raptly from over the railing, a creator beaming down at this new world he’d made.

Scheduled for April 10th, the game’s epilogue event will be a live socio-reengineering seminar, sponsored by the Jejune Institute. Seating is limited to 200 people, with priority given to players who have been through Acts I to IV. For those able to get in, Hull promises a magical experience. “We’re actually scaring ourselves,” he told me. “What we’re attempting right now we could have never conceived of two months ago.”

But after that day, people walking into 580 California Street and asking for Jejune will be greeted with looks of confusion and, possibly, calls for security. The doorway to the Institute’s world will be shuttered and locked, and our own world will be a little less magical because of it.

1 Pronunciation is key: It’s a soft ‘je’ sound on that second ‘j’, rhyming with the final syllable in Gerard Depardieu’s last name.

2 Or, better yet, go to the official website, which explains it much better than I could.

3 Unfortunately, I might add.

4 If you’re still having a hard time grasping this, think of one of those murder mystery weekends. (You’re probably familiar with these less because you actually participated and more because they were one of the go-to plotlines for late ’80s, early ’90s network sitcoms.) And then extend the timeframe in which the game is played. And the environment where it takes place. And the amount of ways you can receive information. And without having to leave a tip.

5 Most ARGs are part of viral marketing campaigns for various movies or TV shows. In 2007, the company 42 Entertainment famously created a series of websites “designed by The Joker” that led fans on a hype-building scavenger hunt through San Diego, the setting of that year’s Comic-Con, which ultimately culminated in unlocking teaser photos and audio clips for The Dark Knight. Almost instantly the photos and clips were uploaded to the Internet, so someone didn’t have to go through the actual game to get that reward, but there’s an argument to be made that going through the scavenger hunt in real-time was the reward in of itself. You know, journey v. destination stuff.

6 A number of these participants joined forces and created a massive Yahoo! group account dubbed “Cloudmakers” as a way to share information with one another. There’s a good psychoanalytical paper to be found in examining the collaborative aspect of these ARGs, but I’ll just settle for the following armchair observations: As of this writing, there’s an 81-page forum post on the website UnFiction.org devoted to the various sections of Nonchalance, helping gamers trade information about where to go and how to complete certain goals. While you’d expect the tone of an Internet forum like this to be more along the lines of “I did it first and here’s me bragging about it and spoiling it for you” the posts are actually gentle, almost-parental, nudges to help gamers who are stuck, always being mindful not to ruin the blissful experience that comes with solving a puzzle on one’s own.

7 Probably unfairly so, seeing as The Beast was created by an entirely different set of designers from A.I., the only narrative crossovers being that both take place in the future and the appearance of Salla, an extremely minor character in the film who was most likely shoe-horned in to connect the two projects.

8 If you can find the YouTube video of the event, or any number of photos from various news organizations, Hull is disguised in a blue hard hat and orange construction vest.

9 Not to mention that it takes place in a variety of locations. While Act I takes place in Chinatown, Act II takes place in SF’s Mission District, the “in road” being a 1-watt radio transmitter located at the top of Upper Dolores Park playing a 45-minute, NPR-sounding show, alerting anyone with the patience to listen as to what tasks they have to complete in the area. This second Act took about 6 hours to complete as opposed to the 2 hours spent on the first Act. (Needless to say, there was a moment that second day, sludging through the sporadic but constant San Franciscan rain and trying to break the codes with my then-girlfriend, that I didn’t think the relationship was going to last through the afternoon. And now that I think about it actually, if I were to look back on things through just the right prism, this could’ve easily been the inciting event for our eventual break-up.)

Act III, meanwhile, takes place in the Coit Tower park section of SF. From what I understand — we left before going through it; like I said, relationship on the rocks — this third act utilizes PDAs in a more straightforward way, allowing players to hold up their iPhones or whatever web-surfing doo-hickeys they have in certain positions around the park to view videos shot from that specific location showing events from the past, kind of like watching through a mini time portal.

Act IV is described a bit later in the piece, but I was mostly sworn to not reveal too many specifics. I will say it’s the first part not to take place in San Francisco proper and is the most “hands-on” section of the game. As such, I had a hard time seeing how the programmers were going to make it “perpetual” like the other parts, but they were certain they’d find a way.

10 The Game Bible being the basic construction and plot points of the actual story. When I asked Hull about his literary influences, he stumbled towards naming McSweeney’s and Kurt Vonnegut before finally settling on Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 as the main influence. The tilted rabbit head-shaped symbol that accompanies game locations is a direct descendent of the muted post horns of the Tristero in Pynchon’s novel.

11 Hull says there was about a 50% drop-off with each act, meaning that when the group debuted Act IV, about 120 people were ready to participate in it.

12 While I was sworn to secrecy about where this specific action takes place, there are enough clues in this piece for you to find it if you’re looking. So have at it if you’re one of those types.

13 While in the alcoves of the mausoleum, I pointed out to Hull the odd way the ashes are stored there: They’re in books. One person’s remains are stored in a book standing upright, surrounded by that person’s family, also in books. A large Italian family sat on a ledge like an encyclopedia of their lives. “I love that,” Hull said. “Everyone has a story.”

Rick Paulas is a writer living in Los Angeles.

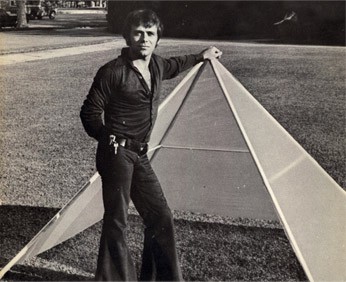

Top photo courtesy of The Jejune Institute.