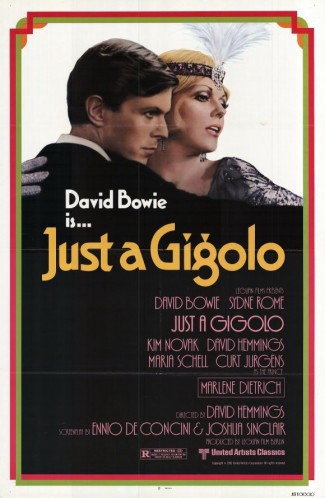

David Bowie's Forgotten, Campy Berlin Gigolo Movie

by Anthony Paletta

To attempt any ranking of David Bowie’s work in movies on a scale of strangeness seems a fool’s errand; there’s no computer on earth that can tally up respective curiosity points for playing both Nikola Tesla and Pontius Pilate, Andy Warhol and The Snowman, The Man Who Fell To Earth, and The Man Who Would Be Goblin King. That said, it’s difficult to find a Bowie performance more abjectly forgotten — and yet so wonderfully bizarre — than the Weimar-set 1978 black comedy Just a Gigolo. Perhaps, you ponder, it was just a cameo? Nope, he’s the star and the rest of the cast is filled out by — get this — Kim Novak, David Hemmings, Curt Jurgens, and Marlene Dietrich (in her last film role). It’s also alleged to have been the most expensive film made in Germany until that date. Still not ringing any bells? You’re not alone.

There are reasons why this film is obscure. It is, in the most charitable possible evaluation, a mess: Bowie has described it as “my 32 Elvis films rolled into one.” And yet life on that ever-dwindling island of not-on-region-one DVD films is a harsh fate for any film and particularly for this one, which is at least as interesting as its cast suggests and a good deal more. You don’t need to dig out the VHS player to watch Mick Jagger run an agency of gigolos in The Man From Elysian Fields — you shouldn’t have to do so to watch Bowie play one.

The late 70s and early 80s were a banner period for goofy-but-fascinating Weimar-era English-language international productions, movies like Bergman’s The Serpent’s Egg, Fassbinder’s Despair and Lili Marleen. Given a context in which sending Dirk Bogarde or Keith Carradine to West Germany seemed like a not-uncommon foundation for a production it’s little surprise that David Hemmings (who both acted and directed, now somewhat portlier than when he appeared in Blow-Up, and looking for all the world like a moonlighting Paul McCartney) was able to enlist considerable funding for this “highly-ironic, tongue-in-cheek” directorial project, including, it was rumored, $250,000 to induce the 77-year-old Marlene Dietrich out of retirement for two days’ work. Bowie was evidently interested in meeting Dietrich; as it happened, she was filmed in Paris, while all of his scenes were filmed in Berlin; their scenes were then edited together. Few things are ever quite fair.

And Bowie? Well, the basic details of his Berlin sojourn are no doubt familiar; trying to kick a mounting cocaine addiction and drawn by the stranded glories of West Berlin and energy of German music he moved to that city in 1976 and spent three years there: life in cheap Schöneberg, check; Iggy Pop as roommate, check; Low, a hit; Heroes, recently finished, also a hit. He agreed to star in Just a Gigolo as a favor to Hemmings (as well as an excuse to meet Dietrich), and no doubt lived a schizophrenic life during the duration of the shoot; how often have you donned Prussian military garb during the week and helped Brian Eno mix Devo’s Are We Not Men? We Are Devo on the weekend? (Another rumor surrounding the production is that Eno appeared as an extra; if he did, I couldn’t find him.)

The film’s international pedigrees begin at the title. A 1928 Austrian song “Schöner Gigolo, armer Gigolo” had already been redrafted into English in the early 30s as “Just a Gigolo” en route to recordings by Bing Crosby, Louis Prima, Louis Armstrong, and Irène Bordoni (hers for a 1931 movie of the same name). Naturally, Pynchon couldn’t resist the tune; Franz Pökler sings a riff, “A Victim in a Vacuum” in Gravity’s Rainbow. (You may remember David Lee Roth recorded a version far later, but that’s a story for another day.)

In any case, this title, in either language, plays out against the arrival of proud Prussian Paul Ambrosius Von Przygodski (Bowie; given the inflated length of the character’s name, we’ll dispense with it, like the Reichsmark, for the rest of the piece) at the Western front, where he reports to Captain Hermann Kraft (Hemmings). Bowie is (naturally) nonplussed by the carnage around him. He stands unflappable on the edge of the trench as Kraft asks:

“Would you like to come down here?”

“Is it absolutely necessary?”

“It is customary.”

Bowie consents to come down.

By a singular stroke of ill fortune, Paul reported to the front approximately two minutes and forty-five seconds before the end of the war, yet also about two minutes and fifty seconds before being knocked out in a shell blast. He awakes to find a sheet up to his nose, his head swathed in bandages, and a brass band playing “La Marseillaise.” Yes, there’s been a mix-up; David Bowie might be a chameleon but he’s never been French. The band departs in high bumptious indignation from the hotel room. From this point, Bowie’s character must struggle to get back to Berlin, which takes him quite a while as two years have passed during the title sequence, during which we see an assortment of footage that looks like it might have been too free-spirited for “Berlin: Symphony of a Great City” including a merry file of riders on extra-tall unicycles in front of the Brandenberg Gate.

This tale, of the delayed return from war, is nothing new. Don’t confuse this with that other film about combatants getting back late from the Great War whose title is borrowed from a song; that’s Laurel and Hardy’s Pack Up Your Troubles. Tonally, the similarities don’t end there though; when David Hemmings described the film as “tongue in cheek” he was clearly engaged in a bit of puckish Hemmings-like understatement; some of the film is wryly comic, some is blacky portentous, and some is straight-up slapstick. Bowie’s return to Berlin, cradling a pig, sees him immediately chased by a ravenous crowd (cue Germanic chase music).

Crowd: “He’s got a pig!”

Bowie: “Get your own pig!”

Before the crowd was overtaken with bacon dreams, we also had a glimpse of Bowie’s one co-written contribution to the soundtrack, the Weill-and-Brecht-like “Revolutionary Song” which we see sung by his sweetheart Cilly. The song is, not to put too fine a point on it, bad, but take a look for completism’s sake. It’s been speculated that Bowie’s only lyrical contribution was the series of “la-la’s.” The song was released as a single in Japan, somehow.

Back home though. The war years have clearly been rough, and Bowie returns to find his home turned into a pension and once-familiar rooms occupied by an assortment of Grosz-like lodger-grotesques. His aunt Hilda is disappointed with his return: “Oh my boy, if your father hears that all you’ve brought back from the war is a pig he’ll have another stroke of paralysis.” Bowie’s martinet father, clad only in military costume, hasn’t, of course, spoken a word since the surrender. His mother, good heavens! now works at the local Turkish bath.

His economic prospects are not auspicious. We’ve heard this story before also, from Alfred Döblin, and, of course, Bowie idol Christopher Isherwood. As Isherwood wrote in The Last of Mr. Norris, in 1935:

And morning after morning, all over the immense, damp, dreary town and the packing-case colonies of huts in the suburb allotments, young men were waking up to another workless empty day to be spent as they could best contrive; selling bootlaces, begging, playing draughts in the hall of the Labour exchange, hanging about urinals, opening the doors of cars, helping with crates in the markets, gossiping, stealing, overhearing racing tips, sharing stumps of cigarette ends picked up in the gutter, singing folk-songs for groschen in courtyards and between stations in the carriages of the Underground Railway.

As a credit to his imagination and that of the screenwriters, Bowie doesn’t do any of those things, but he does spend a stint carrying towels in a bathhouse and then serving as a walking bottle-advertisement. Think the Eat-At-Joes Man, only instead of sandwiched between planks encased in a huge bottle. Cue also the scene of attempting to enter the urinal in this get-up — here’s one of the slapstick interludes I mentioned. The prostitute lodger upstairs comments, “I think shame belongs to another decade. You shouldn’t be ashamed of your bottle either; it’s a wonderful hiding place until you’ve found yourself.”

Prussian Bowie has definitively not found himself. Prussian Bowie is drifting and lost. Prussian Bowie finds no solace in offered sex. Turning down the overtures of Cilly, he says, “You’re behaving like an actress, like some sexed-out, irresponsible immoral slut.” Captain Kraft (Hemmings) who Bowie hasn’t seen since the war, offers a glimpse of hope; he indicates that he will “show you such things as will change the philosophy of your life.” What Hemmings shows Prussian Bowie is an abandoned U-Bahn car in a tunnel, a scratchy Victrola, nascent Nazism, and an angry paramour named Otto. Otto: “Because of your rosy cheeks I know you think you’re pretty enough. Do you think you can jump into our bed?” No, this isn’t at all what Bowie was thinking.

Bowie comments to Cilly, “It’s just that I think I’m coming very close to my lifelong purpose.” “What purpose?” asks Cilly? “Bowie replies, “Well, I’m not sure yet, but people are taking notice.”

It may seem superfluous, having reached this point, to note that the film’s dialogue leaves a bit to be desired; its script was written in English originally but is a remarkable simalcurum of a cut-rate translation, with lines brimming with superfluous exposition, unnatural phraseology, or both. “To what do we owe this unexpected visit of our housekeeper’s socialist daughter?” is a perfect line for that segment of the audience who might have thought that singing lyrics like “When all we want is everybody free/The universe would be one brotherhood” in the street was merely a common day job for the indigent in Berlin, and offered no reflection of political beliefs. To hear Bowie offer lines like “I don’t think we should play around until the Kaiser returns” is a pleasure of its own though.

Moving on, Cilly receives a contract in Hollywood and skips town. Bowie finds himself at the burial of a deceased officer, which is interrupted by a gun-battle in the cemetery. He and the deceased widow (Kim Novak!?! 20 years post Vertigo, and looking sultry) seek shelter in what seems to be a mausoleum and, overcome by the tension, immediately screw on the floor. She orders, “Charge, Lieutenant, Charge! Mount! Attack! Victory!”

Bowie quickly becomes bored of being her plaything; it’s convenient that he’s had another offer. He meets Marlene Dietrich in her establishment, “The Eden,” suspiciously full of slim and dapper young fellows, where she offers him Dom Perignon and a new meaningful purpose. “Dancing, music, champagne; the best way to forget, until you find something you want to remember,” Dietrich mournfully but purposefully intones, and then on to practicalities. Dietrich: “I’m the head of a regiment of sorts… of gigolos.” Bowie, roundly bored, assents.

Those of you who expected some increase in sex in this point are of course bound to be disappointed, because 1. the movie by now is almost over and I don’t mean to give away much more 2. you should have known better, given that the genre of “gigolo” films is almost without exception an exploration principally of male alienation, not of well, coupling. Ask Richard Gere. Gigolo-in-Weimar-Berlin might seem a terribly heavy-handed theme for a film, and in ways it is; yet there’s something of merit in the dramatic conceit of voluntarily turning to self-sale in a society in which any almost any option smacked of meretriciousness. Here it seems like a frequently interesting angle on interwar Germany that’s struggling to get out of a clumsy script and a very unfortunate edit.

We can regret the bizarre editing of the film, which saw a 147-minute cut pruned by nearly 50 minutes for US and UK release. I haven’t seen all of the German cut; it unquestionably offers advances of continuity over the English-language versions, yet it too seems short of complete scrutability. If you want to have an extremely disorienting but vibrant adventure in non-linear viewing spend some time surveying the non-contiguous clips of the film in both languages on Youtube (here’s part 1 of the German and English cuts).

For all of the film’s countless flaws though, it’s simply too interesting, inadvertently, intentionally, or historically, not to watch, whether for the sake of Novak and Bowie’s cemetery romp, or Curt Jurgens having a chat with Bowie about screwing his fiancee while Bowie’s in the bath, or for Sydne Roman’s vibrant appearances (lovely star of Roman Polanski’s also-forgotten What?), or Bowie’s father’s metaphoric Junker enraged paralysis made literal, or a lavish dance sequence in a film-within-a-film, or for Marlene Dietrich’s beautiful performance of “Just a Gigolo” near the end of the movie (watch it in the clip above). Also, it’s far from Bowie’s finest acting performance but his natural demeanor, alien yet regal, does suit the part well. He had recently launched the “Thin White Duke” persona; here he’s a natural aristocrat. Oh, and I failed to mention the Greek chorus interludes of two elderly women opining on the passing political situation; think the German Statler and Waldorf in elaborate hats.

Bowie commented, during his sojourn there, that Berlin was a city “cut off from its world, art and culture, dying with no hope of retribution.” And yet he’s back there again in his latest single, “Where Are We Now?, starting off, “Had to get the train/from Potsdamer Platz/You never knew that/that I could do that.” You never knew that Bowie had uttered such lines as “I may be a gigolo, Fraulein Keisling, but I’m not a whore” either, and now’s your chance to catch up.

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, Metropolis, The Daily Beast, Bookforum, and The Millions on urban policy, historic preservation, cinema, literature, and board wargaming. Previously for The Awl, he’s written about Soviet architecture and preservation of Brutalism.