"Silly, Funny Stories About Really Serious Things": A Chat With Writer Jon Ronson

“Silly, Funny Stories About Really Serious Things”: A Chat With Writer Jon Ronson

by Elise Czajkowski

Bestselling British author and documentary filmmaker Jon Ronson has found his way into the weirdest corners of society. His first book, Them: Adventures with Extremists, found him searching for the secret elite group that many extremists believe rule the world. His subsequent books, The Men Who Stare at Goats (which was made into a movie) and The Psychopath Test, explored, respectively, the odder elements of military techniques and mental disorders.

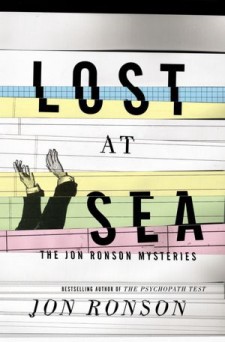

His latest book, Lost at Sea, which is out now, is a collection of Ronson’s magazine and newspapers articles from the last 15 years. Recently, I got the chance to chat with him about the journalism he’s written: the stories that went nowhere as well as the others that mysteriously took off.

Elise Czajkowski: So how did you start out writing about such weird things?

Jon Ronson: Well, I was living in Manchester in the north of England, and working with bands, and not making any money. The bands that I was managing were not flourishing, because it turned out I was a lousy manager. I took people’s potential and did nothing with it. And I was really young; I was only, like, 21, 22. As it happens, I wrote a movie based on one of the bands I worked with, which is about to start filming. So my past with bands has suddenly kind of come into life again.

But, anyway, to make ends meet I started just writing for the local listings magazine, like Manchester’s version of Time Out. And the stuff I was gravitating towards at the beginning was people who lived on the fringes of society and funny, absurd stories about the kind of crazy things that see us through. You know, belief systems that seemed kind of completely irrational to me. And I’ve got to admit, at the time, in my early 20s, I probably thought I was better than them. They were kind of nuts and I was, you know, sane and rational. But the older I get, the less I feel that. Now I feel completely on a par of irrationality with them. So that was it. I was just kind of drawn to those stories, but at the time, they were stories that didn’t really matter. They were just kind of the silly stories about eccentric people.

But then, a commissioning editor at Channel Four Television said, why don’t you take what you’ve been doing and do it about this Islamic fundamentalist in London called Omar Bakri, who says he’s not gonna rest until he sees the black flag of Islam flying over Downing Street and the White House. And I really liked that idea. Treat him not as a kind of monster, but as a human with absurd character traits like we all have. We did this kind of silly, funny story about a really serious thing. And, ever since then, that’s what I’ve kind of carried on doing.

How do you know what will make a good story?

I think about that a lot. There are ingredients, but actually quite often, when you don’t have the ingredients, it still ends up being good, and sometimes even better, so it shows you should never have too many hard and fast rules. But I think at best, it’s a real mystery. There’s got to be something that I don’t know the answer to that I really want to know the answer to. Like with The Psychopath Test. All these eminent psychiatrists believe that psychopaths rule the world. You know, that’s such a big thought. Is there a way I can try and really find out if it’s true? Can I become a professional psychopath spotter, and try and spot psychopaths in positions of power? So that was like a real mystery itself. And then sometimes the mystery is, well, why does this person believe this stuff? So sometimes it’s smaller mysteries. But it all has to be a mystery.

I always hope that there’s a potential for humor. But not patronizing humor. It can’t be condescending. If I find that I’m heading into a sort of condescending place, I abandon the story. But humor’s great. Some kind of absurdity is good. If the thing that the person believes or the situation I’m going to get myself in feels kind of absurd and unfolding. And I think best of all, if it’s a kind of silly, funny story but about a really serious thing. I think that that’s good. So, you know, The Psychopath Test is about mental health and The Men Who Stare at Goats is about war.

Have there been stories that didn’t go anywhere?

Yeah. The main one, the one that was most depressing to me really was [about] credit cards. I had a real sense, like a real prophetic, almost, you know — I’m trying to think of another way of saying ‘prophetic’ that’s even more grandiose.

Like Nostradamus.

Yeah, I had Nostradamus-like sense that things were going to go wrong in the credit industry. And I became obsessed with trying to tell that story. And you know, it wasn’t just me. When the banking system collapsed, every one said, “Oh my god, nobody predicted this.” But actually, loads of people were predicting it. Friends of mine were coming round for dinner and saying, “This is a house of cards.” In my “Who Killed Richard Cullen” story [in Lost at Sea, about an English man who committed suicide in 2005 after racking up enormous credit card debt], there’s lots of people of saying, “You know, this is really bad. This isn’t going to last.”

But I couldn’t do it. I spent three months and I just couldn’t do it. And the reason was because I kept on meeting people who worked in the credit industry and they were really boring. I couldn’t make them light up the page. And, as I said in The Psychopath Test, if you want to get away with wielding true malevolent power, be boring. Journalists hate writing about boring people, because we want to look good, you know? So that was the most depressing one. To the extent that I would like get up in the morning — I’ve never really told this to anyone, but I’d get up in the morning, I’d go downstairs to breakfast and I’d, like, look at my cereal and burst into tears. And then I’d think, it’s only like nine hours until I can sit down and watch TV. After three months of that, I was thinking, I’m actually getting depressed here. So I abandoned it. My editor in New York keeps reminding me that, if I’d carried on with the credit-card book, it would have come out exactly when the banks collapsed and everyone would have turned to me. But I just couldn’t do it.

Have any of the stories you’ve written really affected you?

I think “Who Killed Richard Cullen” really stayed with me. [It] gave me a whole different view on how the world works. Almost conspiratorial, because it sort of is a conspiratorial story about how the people at the top are coming up with kind of clever, almost invisible ways to manipulate us down below and keep us enslaved in their credit cards. So that story. I think The Psychopath Test, that whole book definitely did. I suppose it’s the stories that teach us that the people above us don’t always act in benevolent ways. Those are the stories stay with me the most.

I was really interested, in “Amber Waves of Green” — I think Jon Stewart wanted to talk about “Amber Waves of Green” but I just blahed on about superheroes. [The story looked at the lives of six people of different incomes levels in the US.] The thing that really interested me was the idea that at each income level in that story, people come up with kind of illusory reasons why they shouldn’t get any richer. So Franz thinks its fine to earn $200 a week as long as people talk to him respectfully, which is kind of an illusion, right? And then Dennis and Rebecca, [who] earn five times what Franz earned, said, “Well, if we earn more money then who knows, we might become sex and drug addicts, because people in our church have and it’s such a slippery slope, if you have more money.”

And then the woman [making $1.25 million a year] that’s going, “Well, I don’t want my own plane, because imagine what a nightmare it’d be to have your own plane.” So, all the way up, people are coming up with irrational illusory ways to say, “It’s okay that I’ve been forced into this position in life.” My brother told me actually that other people have written about this idea, that this need to feel respected is a really guiding force in people’s lives. And for Franz, it’s almost a way to keep Franz in his place, So that really stuck with me. And in fact, I’m going to write more about that. I think that’s a really interesting subject.

You interact with a lot of cult leaders and very charismatic people. Do you worry about being influenced by these people who professionally influence other people?

No, I sort of like it when I feel influenced by them. I like a story most of all when I feel like I’ve gone through some kind of change. And on two occasions, that change has happened in a way that I’ve changed for the worse. I didn’t realize it, and it was only when I was writing the book that I changed back again to how I’d been before.

One was in Them, when I really became a kind of paranoid conspiracy theorist for awhile, started thinking I was getting followed when I wasn’t, and all of that. And then the other time was with Psychopath Test, when I became totally drunk with my abilities to spot psychopaths everywhere. On both occasions I really kind of loved that. I’ve always thought, if you’re lucky enough to be able to write a book, you should really go through some kind of hell to write it.

There’s a lot of variety in the kind of stories you write. Do you have a favorite type of story?

I just love going to shadowy places. Like this story I’m doing for the Guardian, which I can’t tell you about, but I ended up in this really crazy housing project in a tiny town in Tennessee, and — I’ll tell you one thing about it. Every apartment in this housing project had a loud speaker, so the person downstairs at the reception could talk to everyone at once. And when I was there and that happened, I [was] just so elated to be somewhere where people don’t get to go, and people don’t get to see. It’s a kind of mysterious shadowy place, and yet I’m there and I’m experiencing it. I love that more than anything. Adventures into places where people don’t get to go. In Them, I remember feeling the same thing at a Ku Klux Klan compound. People were saying to me, it must have been terrifying. And you know, I had to be wary and on my guard, but more than that, I just felt privileged to be anywhere where people don’t get to go.

[Like] Phoenix Jones, my real-life superhero. He’s not in the hardback in America because Riverhead brought it out as a short e-book, but I’m sure it’ll go into paperback. I still worry about him, that he’s going to end up getting killed. It’s one of my favorite stories.

Almost all of the stories in Lost at Sea take place either in the US or the UK. Have you found a big difference between the US and the UK, in the types of stories and the people?

Not really. I mean the main difference is Americans do tend to be a lot more confident and outgoing and outspoken than British people. Which at its worst means you get more narcissists in America than you do in Britain. That’s the kind of downside of confidence. I’ve met some terrible American narcissists.

Haven’t we all.

Yeah. They’re like my least favorite sort of people. I really can’t stand them. But the upside is that Americans are kind of lovely, especially the more introverted, quiet ones. Other than that, I don’t feel there’s a huge difference.

Do you think being more well known has changed how people treat you?

There are upsides and downsides to it. Like, new doors open and then other doors close. I think they probably balance each other out. So for instance, people who don’t know who I am, that then discover that I have a connection to George Clooney. That helps. And I completely milk it in my introductory emails to them. I always say, my first sentence, “One of my nonfiction books, The Men Who Stare at Goats, was turned into a film starring George Clooney.” That’s definitely opened some doors.

Tell me about this movie that you wrote.

It’s a comedy about being in a band, and its very funny, I think. It’s called Frank. Michael Fassbender plays Frank, and there’s a character based on me called Jon, and it’s about their relationship inside the band. Jon is the keyboard character and Frank’s the singer, so it’s about the relationship between Jon and Frank.

You played the keyboard?

Yes, but not well. I could only play C, F, and G. Luckily the band I was in, all the songs were in C, F and G.

Have you written other fiction?

No, first time. At first, I just couldn’t get my head around it. You know, what we do, whatever happens at this table is our material. But in a movie, you go into a restaurant, you sit down, and there’s fucking nobody there. The restaurant doesn’t exist. It’s like a big white space, and that completely sort of fucked with my mind, because I was thinking, well, there’s nothing to tell me what is acceptable for this script and what is not acceptable. Like in journalism, what’s acceptable is what actually happened, and what’s not acceptable is what didn’t happen. But with fiction, nothing happened, so you have to make these kind of complete judgments on what would the character do that? And it’s like, you could say, yeah, of course the character would do that, because this character doesn’t exist, so he could do fucking anything. He can go up to space, he can do anything.

So that completely screwed me with me for about two years. This was like a five-year process. Then after awhile, these characters start to form, and you do start to think, okay, I know enough about [the characters] to sort of know what they would or wouldn’t rationally do in a situation. So the further into the process you get, the more it actually feels like journalism. Because the stuff you’ve written does exist and then that informs the rest of it. So the second half of the process was actually really similar to journalism and I really liked it a lot. I don’t know whether I could do it again.

It seems like you’re always working. Why do you think that is?

You know what, I asked Randy Newman the same question one time when I was interviewing him, and he said it’s because it’s how I judge myself and how I feel better. And because everything I’ve ever thought has already been thought by Randy Newman, then uh, I think that’s probably my answer as well.

Related: A Chat With Fran Lebowitz and How Not To Die Of Rabies! A Chat With Bill Wasik And Monica Murphy

Elise Czajkowski is a freelance journalist in New York City. Feel free to tweet at her with abandon. Photo of Ronson by Barney Poole.