A Chat With Fran Lebowitz

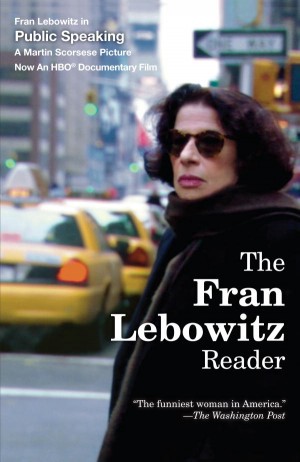

Since the 1970s, writer Fran Lebowitz has been one of New York City’s most important social critics. In 2010, HBO aired Public Speaking, a Martin Scorsese-directed documentary in which Lebowitz opines with characteristic trenchancy on everything from the touristification of Times Square to the concept of fame to her dislike of digital clocks. Last month, Random House released an audio book of The Fran Lebowitz Reader, a collection of essays from her best-selling titles Metropolitan Life (first published in 1978) and Social Studies (1981). I recently spoke to Lebowitz by phone, and we talked about New York and its various incarnations over the past four decades.

MATTHEW GALLAWAY: Was it a challenge to record an audio book?

FRAN LEBOWITZ: A lot of writers complain about it, which I don’t understand. Compared to writing, it’s like a vacation. I mean, yes, I found it to be tedious.

Where did you record?

A studio in a place called the Film Center, which used to be an out-of-the-way place, 9th Avenue and 40-somewhere, I can’t remember. But now, of course, it’s smack in the middle of the 8-billion horrendous tourists. The thing I most remember about it as being unpleasant was that during that weeks I did it, the temperature was like 150 degrees, so that I had to sweat through Time Square to the subway in this horrible, horrible weather. But the thing itself, it’s just kind of tedious.

Could you smoke in the studio?

No, no, no. You cannot smoke inside anywhere in New York City, I mean, any place that you don’t own or rent or whatever. I smoked outside. Which the horrible thing about that, other than being outside, is that it’s in the middle of this incredibly crowded neighborhood there.

Did it take you back in time when you were reading the essays?

Yes, but not in a nice way! I mean, truthfully — obviously — yes. I don’t read these books very frequently, and so it was incredibly disconcerting. I mean, it would not be so bad if I had written six more books, but since that’s not the case, I found it disconcerting. The two books are now one book — The Fran Lebowitz Reader — and it sells very well. It’s in its 12th printing. And just from my own experience of being in the street, the majority of the people who stop me and tell me they have just read it, they are people who are young, and I don’t mean just younger than me, I mean people in their twenties. So truthfully, while reading, I kept thinking to myself, “they have no context for this, I don’t know what this means to them.” I don’t really actually care that much, but it’s an intellectual problem. When I was writing, my focus was a kind of contrarian stance to the counterculture, but to kids now, it represents the counterculture, and so I just think it’s a different thing. I mean, I know it’s a different thing to me. It’s just that they don’t have a context for it, and even at the time, most people didn’t, especially the pieces that were originally written for Interview and ended up in the book. Because in the early 70s, the readership of Interview could fit in one room, so it was less an audience and more of a clique.

One thing that really struck me reading the books was the gay world you described: you reference backrooms, discos, coded bandanas, Jean Cocteau, poppers, the baths, the Westside docks and trucks, Ronald Firbank — I mean, who’s heard of Ronald Firbank now?

My point is that even then no one had heard of him! My friends had heard of him, but we’re talking about a couple dozen people. I really think that just there happens to be a vogue now for this kind of thing.

Are you saying Ronald Firbank is back?

Ronald Firbank was never here. What I’m trying to tell you is that it was always beyond the special taste. I mean, even in Ronald Firbank’s era.

In the documentary Public Speaking, you describe arriving in New York and falling in with a group of mostly older, gay men. Talkers and wits, masters of the double entendre. Your essays really resonate with that kind of banter.

Yeah, I think that’s true. But you’re among the very few people who would notice that. I’m happy you noticed, I mean, “happy” may be the wrong word, but, yes, because people don’t even know. The memories of people are very short. As we know, because otherwise we certainly wouldn’t still have Republicans in office. People don’t remember things that happened in their own lives. I have friends who are my contemporaries, okay? They lived through the same era I lived through. They were with me. And yet I’ll say something, and they’ll go, “No, I don’t remember that.” Partially that’s a result of the drug taking, but partially some people just accept what’s happening and keep going. This is maybe a good thing for life, but it’s a bad thing for art.

In the documentary, you mentioned what AIDS did to the gay audience that used to exist in the city. Do you mean actual numbers, or an aesthetic, or both?

So truthfully, while reading, I kept thinking to myself, “they have no context for this, I don’t know what this means to them.” I don’t really actually care that much, but it’s an intellectual problem.

It’s not that there’s an insufficient number of gay men, it’s that they’re different. The point I’m trying to make is that this particular generation tied on a mask. There was a break in the culture. But additionally, the idea — and not just the idea, the actual life of homosexuals — changed immeasurably because of the acceptance of homosexuality. And that was because of AIDS. No one ever says that. Or how AIDS caused gay marriage. I mean, it would never have existed. You could pretend to your family that you were straight, but you couldn’t pretend you weren’t dying. And also, people became scared, not just of AIDS, which was a sufficient reason to be terrified, but also because — and this is the other thing no one ever says — the way that AIDS spread, by which I mean the rapidity, which was caused by a level of promiscuity that never existed before or since. And I really believe that people made these kinds of bargains with themselves. You know, I’m not saying I have this on the record but from what I could see from the people I know who survived that era, it was like, “don’t kill me and I won’t do this anymore.” Also, most straight people never thought about gay people before AIDS, which is why I could publish this stuff, go on a national television show and never be asked about it, in the way you are asking me about it. They would focus on other things. And after AIDS, I think that [homosexual] people were afraid of a kind of official response to AIDS, like they would be arrested, or put in jail, all these kind of things, which are not unlikely things, by the way, and so they made up a lie. “We’re just like you. We are just like you, we’re exactly like you.” But of course, they were not exactly like straight people. They were nothing like straight people.

How so, exactly?

At some point in the 70s, I remember being in an S&M; bar, I can’t think of which one, but in a bar with a friend of mine, a guy. Women were not allowed in this bar, so I had like a special dispensation. I was there as an anthropologist, let me assure you, and I said to him, “If straight people knew what was going on in here, they would send the army in.” I really believe that. It was a way of life for a relatively brief period of time that was stopped by AIDS, and it never came to public knowledge, because it was kept hidden. And it was hidden because people were afraid, and then these people died. I mean, there cannot be many who did not die, and those who were left just made this thing up. “No, we’re just like you, we just want to get married and have children.” And now gays are just like straight people. They’re just like them, or largely like them. The difference between gay people and straight people now has more to do with gender than with sexuality. Men are men whether they are gay or straight. And so, basically, I mean, to me, to see all these gay people with children, I can’t get over it. I think, “It’s unbelievable that you will do this when you don’t have to.”

You also reference a kind of lost era of cultural mentorship, where older gays would take the younger ones under their wing and bring them to the ballet and the opera, give them books by Ronald Firbank and so forth.

I mean, in a certain way, it depends where and when you were. This was more true in New York than San Francisco. In San Francisco, you had — how should I say this — a very “lively” scene. You didn’t have to be very smart, let me put it that way. In New York, being gay was not enough. Here, there was a hierarchy that had to do with intelligence or with a certain kind of cultivation. And partially this was caused by the invisibility of homosexuality in the culture. There was just no awareness of it. It just didn’t exist, but it also operated kind of like a secret society. And so part of the older men taking younger men to the ballet, part of that was — If you want to call it — mentorship and part of it was just seduction. So some of what you say was true, but not in the nice way you put it. There was a lot of hierarchy. Drag queens, for instance, who now are embraced in every living room in America, were generally considered very low on the social scale. There was a lot of contempt for drag queens, not all, but there was a certain amount of contempt, and it was considered to be a kind of a trashy thing to be a drag queen. Or to be a hairdresser — or other professions that were kind of conventionally gay professions at the time, like if you were a choreographer. Gay hairdressers were called “hair benders” and “hair burners,” and they were really looked down on because it was a “stupid” profession. By which it was meant a profession where you didn’t have to be smart, a lower-level profession. I also cannot stress enough to you how minute this world was. When I talk about it, it makes it sound like some sort of global thing, but it was very tiny. It was tiny here; and in every big city, there were similar scenes. But there was a big difference between cities, and certainly between a city like New York and a city like San Francisco.

I saw a documentary a few years ago about the Cockettes in which someone describes how, after the Cockettes arrived in Manhattan from San Francisco, they were hanging out one night in a bar and Candy Darling swept in and was just repulsed or disgusted by these “dirty hippies” and so she swept right out. Which I mention because it seems to epitomize the kind of hierarchy you’re describing.

That’s right, and, yes, I remember the Cockettes because I was an usher at the opening of the Cockettes. I desperately needed the money and I was supposed to be paid $90.00, which I never got, but among the people I showed to their seats were Gore Vidal and Angela Lansbury. The story is that someone saw the Cockettes in San Francisco, someone from New York. I can’t remember who, it might have been Truman Capote, someone like that, and he said, “You’ll see how brilliant they are.” And they came to New York. They were in a theater on Second Avenue, I can’t remember what it was called. There was a lot of hoopla about their arriving. In fact, I went to the airport to meet them in a bus. A press bus went from all the little, underground magazines. And until they performed, everyone loved them here. They were funny. The idea was that they didn’t try to look like women. Which Candy did. I mean, Candy was often mistaken for a woman, although really, to me she wasn’t a woman, she was like a big guy. The Cockettes had beards, okay? And so, that was the thing that was witty about the Cockettes, in my opinion. But their show was really terrible. And we had Charles Ludlam here. He was really brilliant! There were really brilliant people doing things like that here, and so the Cockettes, I think, the opening night was the only night that they performed. You never saw people turn so fast in your life. As everyone came into the opening, there was all this anticipation, everyone was going to love them, and within 20 minutes, it was over for the Cockettes.

If you were a teenage kid right now looking for some place to move, do you think it would still be New York City?

I don’t know. People are not so isolated anymore. Because of the Internet and because of the popular culture in general, where people actually are is certainly a lot less important than it used to be. There’s no question that geography is fast disappearing in a certain way. The New York that I came to doesn’t exist anymore. The little town I left is still there, but it’s as changed as New York is. So, it’s really impossible for me to imagine. There’s not the same need to go to cities as there used to be for some people, depending upon whether or not you like to live in cities, which I do. People don’t have to escape so much anymore. It’s not as restrictive to live outside of the big city now. There’s not the same kind of convention anywhere. It’s not that there are no conventions, but they’ve changed. It used to be that small towns were suffocating because everyone knew you and everyone was watching you, but that really doesn’t exist anymore, even in small towns. People don’t even know who lives next door to them. I hated being watched all the time as a kid. I really couldn’t stand it. But people aren’t watched like that anymore. No one cares.

Do you think it’s that nobody cares or that we’re too overwhelmed by the need to scrape out an existence?

It was shocking, especially because we were the only generation that thought sex was really good, like vitamins. We thought that about drugs too, okay? Sex was really good and the more sex the better. It was helpful. Like now, the way people think of bike riding, which I think is a childish activity.

Well, I think people always need to make money. There was not some utopian era where they gave you everything. But values have changed so much. Standards and values, everything’s changed immeasurably. It is as different a world as if we’d all gone to live on Pluto. So it’s really hard to make these comparisons. Or it’s inaccurate to make them is more what I would say. I don’t know what it’s like to be young now. I can observe things. But the generational observations that you make from this distance cannot help but be wholly inaccurate. It depends on where you start, and that’s what I keep telling my friends, my contemporaries. They say things like, “Well, kids now, they’re constantly texting and constantly on the Internet, and they don’t have conversations.” Or “they don’t have friends, they think a friend is someone they meet on Facebook. They never see their friends. They don’t know these people.” And what I would say to my contemporaries is that these kids’ definition of a friend is completely different than theirs. To me and my generation, it does not seem like a friend. To kids, it seems like a friend. They are completely different than we are in that way, completely different. And you see middle-aged people who are half in, half out. Like Anthony Weiner, the thing that happened to Anthony Weiner, I believe, would not have happened to someone older or younger than Anthony Weiner. He was young enough to use this technology, but too old to know how to use it correctly. Someone my age would not have used it in that way, I believe, and someone younger wouldn’t have made the mistake he made.

You don’t think politicians will have sex tapes in the future?

You mean people who are now in their twenties? They won’t care. People who are in their twenties will have already done this stuff, so there’s now a record. When those people are old enough to be in charge of things — which by the way I don’t ever want them to be in charge of things, and luckily, I will be dead when these people take over — everybody will have that vulnerability. When everybody is vulnerable to something it’s not a weapon. It’s like being gay. It used to be you could blackmail people, and now I would say no one cares. It’s hard to imagine an environment in which you could blackmail someone about being gay. It would have to be an environment of intolerance. Like the right-wing Christian preachers who tell everyone to hate people who are gay and then they turn out to be gay. So they’re vulnerable, but unless your profession is hating other people, you’re not really a candidate for blackmail anymore.

You’ve described having a three-decade bout of writer’s block. Do you ever worry that it might be permanent?

No. I don’t think that. Other people may think that, but I don’t think that, and luckily my concern about what other people think has never been that high. By the way, this is one of the things that I would not blame other people for thinking. But I do not believe that, and no one will ever accuse me of being a cockeyed optimist.

I’ve read about other artists and writers who lived through the worst of the AIDS epidemic and felt like they had to take a break from their art. While reading your book, I wondered if that might have been the case with you, because the world you described was essentially obliterated.

It is exceptionally charitable that you call these 900 years “a break” but I’ll take that. And yes, it was very shocking to live through. It’s always shocking to young people when their contemporaries die. Even in a war, it’s shocking. I mean, as a soldier. It was shocking, especially because we were the only generation that thought sex was really good, like vitamins. We thought that about drugs too, okay? Sex was really good and the more sex the better. It was helpful. Like now, the way people think of bike riding, which I think is a childish activity. I know people now think the bike is a sign of virtue and I think it’s a toy, but we said sex was good for you and it turned out to it could be bad for you. Really bad. And yeah, people became terrified, of course. People were “terror-stricken” is the term I would use. And because when you look at it in retrospect, like all things you look at in retrospect, it seems very linear. The great thing about history is that it’s in the past and people have time to compile a narrative, but that’s not how it seems when you are living through it.

Except you claim that people don’t want to acknowledge this shock and terror now, as part of the narrative.

It’s because there are hardly any survivors. This leap was made that was… I wouldn’t say “orchestrated” because there’s no way anyone could have imagined what would happen, but the behavior… Now look, when I say the “behavior,” I don’t mean the virus, okay? Because one thing that people really quickly forgot about AIDS is that it’s a virus. I did not forget this. I argued with the people from ACT UP and with all those people who made a kind of political activity out of something because they were afraid that the other side would make it into a political activity. I was always fighting with them and saying, “You are making a metaphor of a virus, which is what you were afraid that straight people were going to do.” But it was a virus. It still is a virus, like the flu or like a million viruses. So, I think that people stopped talking about it because there weren’t that many survivors, and because this big lie took its place, and this big lie was invented by people, not as a defense mechanism, but as a defense. Ronald Reagan was the president. Now he’s being looked upon as Santa Claus, but he was horrible, really horrible. And not just Ronald Reagan, but the world was made up of more Ronald Reagans than of anyone else, and so gay people were afraid and they made up this big lie. You know, “No, I haven’t had sex with 40,000 people in dark trucks, I’m just like you.” And so they didn’t invent the virus, but the spread of this virus, the rapidity at which it spread, of course it was caused by this promiscuity. Of course it was. It’s the same thing with a regular cold virus. If you’re alone in your house with a cold, no one’s going to catch it. If you go into a subway car and you sneeze on everyone, the subway car’s going to catch it. So there’s this blank space in history where the story breaks. In every kind of documentary or anything written about at the beginning of AIDS, they always show you that piece in The New York Times, someone in their house, Fire Island Pines, reading this headline. But that’s not how it was. And they show it because they don’t have time to explain, and five minutes after that everyone’s dying, and then two minutes later, everyone’s getting married. Okay? That is just not true.

The Awl is read by many people in the 25- to 35-year-old set. Anything you’d like to say to them in parting?

Well, when you get the power, if that ever happens, please change these stupid smoking laws. That’s my main message to them.

This interview was lightly condensed and edited for purposes of clarity.

Fran Lebowitz will be appearing at Town Hall on October 20 in a discussion about politics with Frank Rich. For a full schedule of her appearances, please visit her events page on Facebook.

Matthew Gallaway is the author of The Metropolis Case.