Quit Your Job (But For The Right Reason)! A Chat With Writer Jami Attenberg

Quit Your Job (But For The Right Reason)! A Chat With Writer Jami Attenberg

by Michelle Dean

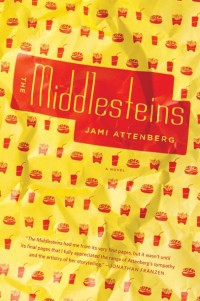

Jami Attenberg’s The Middlesteins, which hits bookstores today, tells the story of a Midwestern family whose matriarch is binge-eating herself to death. There’s a lot of talk about the obesity crisis in the country, but it tends to happen along one of two set tracks: either accompanying stock footage of headless fat people, or else coming from sinewy trainers barking at the imagined laziness of their frightened charges. It’s fair to say that people are ready for another kind of story, and The Middlesteins has the potential to fill that gap. It isn’t a polemic about the sagacity of good nutrition, or about personal foolishness. It’s about how and why people imagine themselves not to have enough and, in the absence of knowing what it is they’re missing, replace that with food.

If you can’t already tell, I think The Middlesteins has deserved the advance buzz it’s received. It has the potential to be breakout hit for Attenberg, but it’s actually the Williamsburg-based writer’s fourth book. Like many of us trying to make a living by our crappy laptops, she too once had a “real job,” and then quit to write full time. Recently, she and I emailed to talk about what it was like to give up a steady career to write books (spoiler: bumpy), the lure of vices, and even what we should all do about the endless gender-and-literature debate.

Michelle Dean: While I’m desperate not to jinx you, the excellence of The Middlesteins, paired with the pre-publication hype, makes me feel like it’s going to be a breakout hit for you, your first big bestseller. But it’s your fourth novel, which got me to thinking. I think a lot of people would love to do what you did, which is leave a “regular” career to write books, but it seems like your ride into this career has not been without speedbumps. How would you describe your path to being a “professional” writer?

Jami Attenberg: Thank you for thinking that! I am keeping my fingers crossed. Honestly, my first three books did not do so well, sales-wise, so it won’t take much for me to feel like this book is more of a breakout.

Anyway, I don’t recommend you go all in to a creative-writing career like I did unless you have nothing to lose by doing so. I don’t have a family, for example, no future college educations or mortgage to consider. The only child I have to take care of is myself. For the past few years in particular my attitude has been: I’m already broke, what’s wrong with being a little more broke? You sort of just get used to it. You watch everyone around you move forward in their lives in traditional ways, and you accept that you will not be on the same path, especially if you’re a single person, which I am. You just have to give into it, or give up. It’s not for everyone.

I had certain career opportunities that I abandoned along the way. The last long-term job I had was a decade ago, working for HBO, developing interactive content for “Six Feet Under” and “The Sopranos.” There was a lot to like about that job but it never seemed to satisfy me. I had a really strong desire to tap into my own voice, which is hard to do when you’re working on someone else’s vision.

Oh, I didn’t know you’d worked for HBO! But I do wonder often about people in those quasi-creative-class careers, don’t they just feel jealous all the time that they don’t get to self-express, use their “voice” as you put it? When I was a lawyer I at least was in a wholly different world.

I’ve since gone on to freelance in advertising for the last decade, a few months here, a few months there, and I can’t tell you how many creative directors have said to me, “Oh, you’re a real writer,” as if what they do is not writing. And then I’ll be like, “How’s that house in the Hamptons?” And they’ll say, “It’s magnificent.” I don’t know. We all make our choices.

Anyway, when you say you weren’t satisfied… do you mind unpacking that a little? I mean, I started out asking about career stuff because to me there’s an analogy to what happens to Edie Middlestein, the matriarch, in this book. The idea of dissatisfaction was a big part of Edie’s psychology in the book. It led her to binge-eat, to self-destruction. Obviously that’s not where you went with it. Is that a fair analogy?

When I worked for HBO — and I’m sorry, HBO, that I keep bringing your name up, I like your programming a lot! — I was definitely engaged in some self-destructive behavior, drinks, drugs, food, all of that. Though I didn’t go to Edie’s extremes. And it was, in part, because I was dissatisfied with my creative life.

But I don’t even know if I recognized that’s what it was at the time. When we’re in the middle of self-destructive behavior we sometimes don’t recognize we need help, or at least need to change our behaviors. I don’t think Edie Middlestein fully knows she’s in trouble until she’s in too deep.

Yeah, the thing about those vices — drugs, the Hamptons (people kill people there! Just watch “Revenge”!), or in Edie’s case — food, I think, is that they are, like, ersatz risks. Placebo risks. Something like that. It gives you a lull, or a break, from the boredom, but it’s more like treading water than swimming away from the actual problem.

But some people are, you know, happy treading water. All they’ve wanted to do their whole lives is tread water. I felt like the son in your book was like this. He married early, he got what he needed, and his own dissatisfactions are at best vaguely held. Am I reaching, there?

It’s not treading water if it makes you happy. A life that is different from my own — or yours, for that matter, since the both of us live here in New York and are trying to make it as writers — is not boring or simple or lame or a waste of time, if it makes that person feel happy and fulfilled. I don’t think he’s dissatisfied. I think he’s probably the most satisfied out of all the characters. All he ever wanted — a house, a wife, two healthy kids — he actually has. We are only ever as insignificant as we feel.

Well, one strength of your book, I think, is that even though you are a New York Writer and use social media and are therefore some kind of exalted media figure, you are very perceptive and non-judgmental about people in the middle of the country. You’re from there, right?

I’m from the suburbs of Chicago, yes. I was born and raised there and went to high school there and then fled there as soon as I could and went East to college. But my parents still live there, and I really love the Midwest and feel at ease whenever I go home, although when I was growing up, as I said, I couldn’t wait to leave, but I blame that entirely on my early physical development. It took me years to recover from that.

Also, I drive cross-country a lot, usually once a year, and have spent a lot of time in different cities and towns all over America, and I am thoroughly in love with this country of ours. I like talking to people a lot. I like how when I go to different parts of the country people usually pay attention in conversations. Like, they ask a question and they really want to hear the answer to it. I miss that in New York sometimes. People are more distracted here than in the rest of the country. Also, I like the desert, and trees, and mountains, and farms, and the sky. Wide open space. There’s a lot going on out there in America.

One of the other connections your book has to the Midwest, and to literature about it, is a blurb from Jonathan Franzen. Which came at an interesting time, if I recall correctly.

That blurb from Mr. Franzen was extremely helpful, and also it was a delightful surprise, as I have never met the man. My understanding was that my book was just sitting in a stack of galleys that he’d had for more than a year because he is a busy person, and he took them all on a plane when he was traveling, and I just got kind of lucky that it all worked out. It was very generous of him.

I actually hadn’t read The Corrections before I started writing The Middlesteins. When I was about halfway through writing the book I was chatting with another writer, Joanna Smith Rakoff, and I was telling her about what I hoped to accomplish with it, and she suggested I read The Corrections. And after I did, I went back to the beginning of my book and completely restructured it. I mean my structure is nothing like The Corrections, but seeing how he can make a smaller story be so much bigger was extremely instructional to me. I definitely felt like when I was writing my book I was in a kind of conversation with his book. And so for him to hear that conversation a year or so after the fact was sort of what you really hope for when you’re making art. And that you get to be a part of it, even if it only lasts for a moment.

Well, I hope you get more than a moment! But it’s interesting that you bring up the question of conversation, because we seem to spend an endless amount of time, lately, talking about how certain kinds of novels — novels by and about women — get cut out of The Conversation, the allegedly “serious” one, not that there’s only one but you know what I mean. Do you think about that at all, for The Middlesteins? Like what it might be a part of, and what it might not?

I think every writer, female or male, wants to be taken seriously. But obviously it’s sort of ridiculous that after publishing four books that I would even have to be asked that question. At what point can we just reframe the discussion? What if you and I together, at this moment, decided that no woman would ever be asked that question again? What if we just willed that change into existence? Let’s both close our eyes and think real hard about it and see if we can make it happen.

And if that doesn’t work?

I feel sort of hopeless about it, in that case.

Related: Quit Your Job! A Chat With Actress-Turned-Pot-Farmer Heather Donahue

Michelle Dean writes in a lot of places, now. Follow her on Twitter.