Quit Your Job! A Q&A With Actress-Turned-Pot Farmer Heather Donahue

by Michelle Dean

Heather Donahue, best known as the actress from The Blair Witch Project, has written a book. Now this happens all the time, the once-famous-people-writing-books thing. And often the result is some cookie-cutter “memoir” of which the kindest remark you might make is that it has paid some deserving freelancer’s rent for six months. But Heather Donahue’s story caught my eye, regardless, because her book, Growgirl, was said to be about her quitting acting to grow pot. Medical marijuana, of course, all sanctioned by California law, but pot nonetheless, and, being self-interestedly attracted to stories of people who do about-faces in their careers in their early 30s, I was intrigued.

I’m not sure what I expected, but

Growgirl is pretty wonderful. Donahue is not only a funny, sharp, endearing narrator, she’s downright wise about the experience that is, literally, torching a previous life. (Donahue burned a lot of her leftover Hollywood things in the desert before heading north to start her new business.) As a bonus, I learned a hell of a lot I didn’t know about pot. Here we talk about the “lady zeitgeist,” making peace with “tit whiskers” and the waves of fear that come with Quitting Your Job.

Michelle Dean: At the outset of your book, you write that, “I’m sure somewhere on the cover of this book will be the words The Blair Witch Project, and believe me, I will have tried to prevent that.” Plainly, you lost that battle; the movie is on there. How do you feel about that?

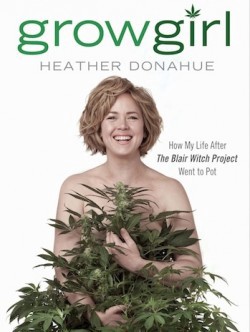

Heather Donahue: My publisher’s first idea for the book cover was basically a reenactment of the Blair Witch confessional scene with a pot leaf on my face. Which felt, um, wrong. So we worked from there. I offered the idea of me, naked with a pot plant, thinking that there was no way they were going to go for it.

As far as books that have their author on the cover go, I like it. I like that it’s nudity, because it’s a very naked kind of book, but it’s a sort of desexualized nudity. It’s a little bit Eve, a little bit Green Tara and a little bit Dove ad. The photographer, Michele Clement, got what I was trying to do and I love the photograph we ended up with.

I just never thought of Growgirl as the kind of book that has its author on the cover. The only book of that ilk that I own is Dolly Parton’s autobiography, because she is awesome. It was more than a little heartbreaking to see the cover mock-up and think, I probably wouldn’t pick this up in a bookstore. At some point, I just let it go and started hoping hard that word of mouth will make up for it.

Oh my god, that first cover idea is kind of horrifyingly smart in a crass marketing way.

The first cover idea is good if we’re talking about a brand, rather than a person. A brand doesn’t evolve in the same way that a person does.

Part of me thinks that I should have written Growgirl pseudonymously and then there would have been no possibility of packaging it as a non-celeb celeb memoir. But then it wouldn’t have really been my story.

The Blair Witch Project continues to repeat on me like cucumbers or chili. I understand why it ended up in the subtitle. I understand why it’s the initial focus of the press coverage. It’s such a weird thing, in terms of its effects on my life: not bad, not good; just big.

Your Dove ad analogy strikes me as apt. Not just because the visual cues are the same, but also because it represents the kind of tightwire you have to walk. You want people to read the book (or feel better about themselves) so you have to sell it. But there are all these pre-set ideas about what kind of things sell that are hard to overcome (i.e., books with their authors on the cover), and some of them end up misrepresenting your work. Because I wouldn’t call your book a Dove ad, either. It’s too raw for it.

I agree that the book is much, much rawer than a Dove ad, but in some ways it’s also more innocent — less concerned with branding, but more concerned with empowerment. One of the big narrative drivers for me is the tension between binary pairs: legal/illegal, public/private, revulsion/attraction, etc.

I understand that a lot of people wouldn’t have that money. I understand that it’s a privilege to change a life. But I also understand that what really changed my life was my decision to write every day, which cost nothing.

Some people have commented that some of the more revolting physical stuff [in one sequence, gastrointestinal issues result from the excessive consumption of energy drinks; in another, she worries about hair growing on her breasts, dubbed “tit whiskers”] is gratuitous, but I would suggest my preoccupying ideas in Growgirl are around identity — and that to get to identity we have to go through the body. As I was all up in my cozy little forest chrysalis, I started to realize how I’d started to become charmed and almost impressed at my body’s adaptations, the attractive ones of losing weight and toning up from all the farm work, and also the revolting ones of callouses and blisters and burning and peeling. Having a good relationship with my body, tit whisker and all, had maybe the most significant effect on my overall happiness. That was why I chose to be naked on the cover, that’s why I chose to be completely naked at the shoot, even though you wouldn’t be able to tell. I was also 165 pounds and a size twelve at the time of that shoot. I think I look pretty fucking lush.

I love that “tit whisker,” which is one of the metaphors that opens the book. I mean, talk about a bodily experience women are afraid to talk and be whimsical about: hair growing on areolae is definitely still in that category. Women are only allowed to talk about their bodies, it seems, to the extent it can be commodified and resold, like the Dove ad.

Ah yes, anal bleaching is okay, but tit whiskers are verboten. So it goes. At the risk of sounding all women’s studies-y, I think the commodification of ladybodies has been more disempowering than any other financial, or social restrictions, because how can we be strong and steady enough to exercise our power when we’re frittering it away by wrestling against our own skins? And really, fuck that. As I teeter on the brink of middle age, I feel better than ever. I am acutely aware of my declining fuckablilty, and my initial struggle with that has largely passed and given way to a softness and humility that has made me fearless.

It fits into a certain tradition of these books, and so I have to bring this up: are you an Eat, Pray, Love fan? I think your quest differs considerably from Elizabeth Gilbert’s, don’t get me wrong, but there’s an analogy here that’s inescapable: media-driven job, longing for something with more spiritual/meaningful calories in it…

I think it’s funny that you’re the first person to bring up Eat, Pray, Love, because I think that book gets a bad rap (phenomenal success will do that to a media nugget, I should know!) and I think Growgirl does have a few things in common with it. Fundamentally, they’re both seeker books. I didn’t have money going in, so doing my travels in other countries was out of the question. I had to get domestic, and I think it served me at least as well. I think the other thing the two books shared is a flawed and chatty narrator who is sincerely trying to answer the question, “How to live?” and willing to fail and fail again.

I can only really talk out of my ass about Eat, Pray, Love. I’ve only leafed through it, and when I did so I could tell my seething jealousy of the money would interfere with my being able to internalize whatever the book might have to offer. I mean, you write in the book about coming from a working-class background, so the class thing isn’t invisible to you, but I wondered if you had any thoughts about that aspect of it.

There’s nothing like growing up in a working class family where your dad up and loses his union job after 30-plus years and everything that he raised his kids to believe about dreams and hard work and freedom has turned to disillusionment, unemployment and debt. Witnessing that first hand in my family, and seeing its effects only made me want to work harder, but not to line the pockets of some abstract mystery douches, that was what I wanted to avoid at all costs.

When I made a little money from acting jobs, I never left the apartment I moved into when I first arrived in LA and was working as a temp. I stayed there for ten years, until I moved to Nuggettown, because it was rent controlled. That’s a reason I still had something left to get my growroom going. I understand that a lot of people wouldn’t have that money. I understand that it’s a privilege to change a life. But I also understand that what really changed my life was my decision to write every day, which cost nothing. My decision to meditate, even if only for 15 minutes. Those two things have a bigger daily effect on my day than anything I’ve ever bought or rented. They were the seeds of the bigger, more systemic changes. And really, anyone can do either of those things. A little silence goes a long way. And laughing.

Do you like “Enlightened,” too? That’s the other thing your book reminded me a lot of.

I love “Enlightened.” When I first saw it, I got goosebumps because I thought, holy shit, this reminds me of my story too. It’s time. The lady zeitgeist is afoot and not a moment too soon. Did I mention that all the marijuana plants are female too?

I agree with you that a lady zeitgeist is afoot, but there are times when it comes all the way back around the bend and bites us in the ass. I mean, it’s not an unqualified boon, in other words. Exhibit A: you talk in the book, a lot, about the skepticism you held of the woman you call Cedara’s Mama Earth stuff. I found your distrust of it so refreshing and true-feeling; like you say, no New Age bullshit, you’re determined to earn your meaning.

But it did put you in opposition to the “pot wives,” the young women who are, as you put it, “like Beverly Hills trophy wi[ves] with more body hair.” On some level you were frustrated with them for sort of sublimating themselves into supporting their “pot husbands.” Is that fair? I know you told the New Yorker and Reuters that one of them heckled you at a reading.

On the one hand, I was frustrated with the “pot wives” and on the other, I was jealous. Here I was, with all my independence, trying to find my place in the world, and then another, and then another — and there they were, at ease, relaxed, being taken care of. God just typing that, “being taken care of” sounds so nice for a change. Some people have suggested that the treatment of pot wives is misogynistic, but I think just because something is anti-feminist doesn’t necessarily make it misogynistic. In the evo-bio sense, the pot wives had a very clear job to do, to nurture, to nourish, to support, and there are times when I wish my life was like that. There are times when I wish I would have just married in my twenties, had kids and a husband, maybe a house. Is that what you mean about it biting us in the ass?

People have called Growgirl a book about me trying to “find myself.” This feels like a colossally oppressive pile of bullshit to me. I would suggest that I’ve known exactly who I’ve been at each step along my way…

Yes, I was heckled by a pot wife at the Humboldt HempFest. She told me to shut up because I sucked. But how could she not get defensive? I was basically critiquing her choice and reducing her to a checklist. Granted, she could probably check off every single item on the list, but is that fair? The pot wives brought my own questions about my choices into sharp relief. I would have been tempted to go the pot wife route, if I’d seen any 40-year-old pot wives.

The idea of gender intrigued me while I was growing, because my first round grew green testicles under stress. And it struck me that I too, was growing testicles as an adaptation to stress. That I was becoming a sort of social hermaphrodite, capable of competing in a male-dominated field — but at what price? It’s taken me a long while and a lot of sitting to recover my softness, and I still have to remind myself sometimes that there’s strength in that.

What I meant was something like: it seems to me that whenever we get too sure of what women “are,” that’s when feminism of any kind ends up failing us, because all of a sudden you have to be a certain way to qualify for ladyness. And it’s never a compromise: you have to be independent, or you have to be a nurturer. Full stop.

The growing of plant testicles in response to stress is an interesting analogy in that sense, because I can see people wanting to step in and object that toughness bears no specific relationship to testicles.

I absolutely agree with you: When we get too sure of what women “are,” feminism ends up failing. I think this is partly because if we stop talking about what women “are” we don’t need feminism anymore.

I think adaptability is very different from toughness. I mentioned the plant balls more as an example of adapting to stress, how if you adapt to become everything to yourself — it’s hard to remember to need. I think of it as softness, because you’re basic position has to be softness, ease, to be responsive to change.

Well, and as to adaptability, do you ever think about going back to acting? Do you ever regret the “scorched earth” approach” you took to it?

I’ve never thought about going back to acting, but I do enjoy the performance aspects of book tour. And I loved being in the band that I write about in Growgirl.

I came to acting from a love of telling stories; it’s how I understand the world. In that respect, I haven’t changed jobs, I’ve just dug to the core of what I really wanted to do, and, with Growgirl, have finally put something in the world that I’m really proud of and want to share. I love collaboration, but I love that writing a book is not really a collaboration. It’s nice to have something (finally!) about which I can say: this is mine

Sort of an aside: People have called Growgirl a book about me trying to “find myself.” This feels like a colossally oppressive pile of bullshit to me. I would suggest that I’ve known exactly who I’ve been at each step along my way, but I’ve also known that to assume a stable self would have just been to resist change and thwart whatever I was becoming. Why would I do that? That’s not a rhetorical question.

Well, and you ended up leaving pot farming, too, because it was too hard, which I kind of liked. I mean, we’ve talked about Eat, Pray, Love. One of the things that I resent about the cultural narrative attached to it is that it implies that if you just “go after your dreams” everything will, in the end, turn out okay.

Of course everything won’t, in the end, turn out okay. It will turn out very not okay at many, many points in your story. And sometimes it will turn out so great you think your head might just pop right on off. The gut compass is kind of a pain in the ass that way.

I didn’t quit pot farming because it was too hard. Writing a memoir is actually a whole lot harder in a lot of pretty fundamental ways than growing pot. I quit pot farming because I decided I was going to write Growgirl and felt that for the safety of myself and the community, it would be better if I got out. I also fell in love with “Uwe,” who was deathly allergic to cannabis. Weird, right? I like to think of weird shit like that as fate, it helps move my story along. Another reason I quit was because I knew it was hard on my parents, worrying about my safety all the time and feeling like they had to lie to people about what I was doing. I didn’t think that was fair.

You’re right: My formulation of “hard” was clumsy. What I meant was something more like: ultimately whatever benefit you were drawing from it, it wasn’t enough to outweigh the burden.

I really liked the passage towards the end you had where you write that “One thing I will miss about this job is that it was really clear what I was supposed to be afraid of: getting caught. It’s a deep and ever-present fear, but it’s also pretty simple, and it keeps other vaguer and more slippery ones at bay.” I thought that was fantastically smart, and at the same time, it made me wonder if it’s the right approach, to keep your psyche away from those questions. It is definitely the Buddhist/mindful one, at least I think so. And yet the act of writing a memoir is diving right back into them, isn’t it? Or was it for you?

I think your new formulation of “hard” is more apt. And also a pretty good metric for when it’s time to let go of something: job, town, boyfriend, cheese.

The work did put the more existential worries to the side in the sense that they were more abstract, and weren’t the triggers. It’s just that they weren’t what triggered the fear tsunami, the more immediate and visceral fears were. Of getting caught, of spider mites, etc. The abstract stuff just compounded those more immediate and realistic fears until it hit critical mass and imploded, then passed. The repeated experience of those terror tides made me more skillful when I finally put on my authorial captain’s hat. Is that a heavy-handed metaphor? Yeah, probably — but it’s also the most concise way I know how to put it.

My garden was a metaphor to a sometimes irritating degree. As goes the grower, so go the girls. [“The Girls” is how pot growers refer to their marijuana plants, who are, remember, all female.] A dog reveals the heart of its master, too. The Girls and the dog were my mirrors, every step of the way. I lost my ability for fiction, thanks to them. When I was fucking up, losing my equanimity to chaos, they let me know instantly.

Interview condensed, edited and lightly reordered.

Michelle Dean writes in a lot of places, now. Follow her on Twitter.