The British Invasion... Again: After The Battle

The British Invasion… Again: After The Battle

by Robert Sullivan

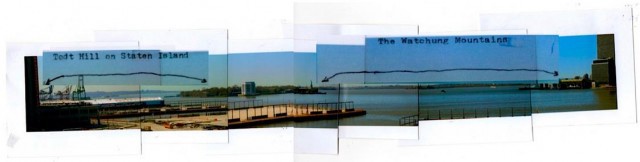

The final installment in a seven-day series exploring how the trail of the Battle of Brooklyn would pass across modern-day New York. Shown in photo, the Watchung Mountains.

It’s over. The Battle of Brooklyn is done, or at least it was on this day 236 years ago, with the Americans momentarily out of reach of the British, having evacuated to the island of Manhattan.

The British were shocked. “In the Morning, to our great Astonishment, found they had Evacuated all their Works on Brookland and Red Hook, without a Shot being fired at them,” a soldier wrote. Earl Percy wrote to his father, the Duke of Northumberland, from Newtown, a village in Queens, which the British now controlled, saying a British victory was at hand. “They feel severely the Blow on the 27th & I think I may venture to assert, that they wilt never again stand before us In the Field. Every Thing seems to be over with Them, & I flatter myself now that this Campaign will put a total End to the War.”

On the other side of the East River, a minister in Manhattan watched the Americans came ashore, out of breath, bedraggled, their spirits transformed, after only the first battle of what would be a long war.

He wrote in his diary:

In the morning, unexpectedly and to the surprize of the city, it was found that all that could come back was come back; and that they had abandoned Long Island. … [I]t was a surprising change, the merry tones on drums and fifes had ceased, and they were hardly heard for a couple of days. It seemed a general damp had spread; and the sight of the scattered people up and down the streets was indeed moving. Many looked sickly, emaciated, cast down, &c;,; the wet clothes, tents, — as many as they had brought away, — and other things, were lying about before the houses and in the streets to-day; in general everything seemed to be in confusion. Many, as it is reported for certain, went away to their respective homes. The loss in killed and wounded and taken has been great, and more so than it ever will be known. Several were drowned and lost their lives in passing a creek to save themselves. The Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland people lost the most; the New England people, &c;,. it seems are hut poor soldiers, they soon took to their heals.

The invasion of Manhattan was imminent. Washington was not feeling good about it. He wrote to the president of Congress: “… with the deepest concern I am obliged to confess my want of confidence with the generality of the troops…” By the end of the war, his feelings would change, but right now, he despised the militias.

After the Battle of Brooklyn, there was another end-of-summer rainstorm, lightning killing American soldiers in camp. And then fighting begins in Manhattan, British troops landing at Kips Bay, on September 15, just below what is today the U.N. There will be a battle in what is today Central Park, where the British, thinking they’re winning, use a fox hunting call (indicating that the fox was about to be caught) to insult Washington, and Washington, a fox hunter recognizes it, after which the British lose. A friend of mine spent a year or so walking and looking around before he could see the outline of the valley in which this battle took place, in and around McGowan’s Pass, but now he swears he can see it. Eventually, George Washington moved his headquarters to the Bronx, at the Morris mansion, Washington Heights, a house Bob Vila once visited, on a campaign through the area.

As fall came, action went up in to Westchester — the Battle of White Plains — and then back into upper Manhattan, near Mount Washington (the mount was already named for Washington in 1776). At last, the British pushed the Americans out of Manhattan, at which point the American fled Fort Lee, raced down through Hackensack, burning bridges behind them. They crossed the Meadowlands, and then got to the Delaware, which they also crossed, General Glover once again taking all the boats from the British side and carrying them over to the American side, in case.

And so we are poised, by Christmas, for the Crossing of the Delaware, and then, 176 years later, for the first reenactment of the Crossing of the Delaware, begun by a theater impresario, history buff and inventor of the Smellodrama, St. John Terrell. The crossing is reenacted every year, as it is in this video, in which Washington is played by a local police officer. (I saw this particular Washington play once, though “play” does not seem like the right word as the reenactors refer to themselves as “living historians.”)

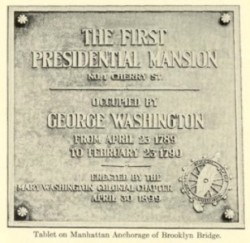

After crossing the Delaware, Washington will bring his troops back within striking distance of New York City — oh, how he wants to take the city back, even though his allies, chief among them the French, really don’t think he should bother. When he comes back into town, he rides his white horse down Broadway — that’s the kind of guy he is — and a year later, sets up in the first White House, on Cherry Street, now beneath the Brooklyn Bridge. There used to be a plaque but I can’t find it anymore.

The key to the winning of the war, from a geologic standpoint, is the Watchung Mountains, pictured at the very top. I don’t want to go too deeply into it here; you could read a book about it. But I will say that you might not have ever noticed them before; that they are mountains even though you don’t think they are and that geologists who study the history of American warfare see them as more than significant, especially since Washington set up camp behind them, in Morristown, New Jersey. “Washington’s choice of winter quarters at Morristown behind those natural redouts was a stroke of genius,” wrote the geologist Bradford Willard in a 1963 essay entitled “Geology and Wars: A Neglected Factor in Wars Within the Continental Limits of the United States of America.”

Something that bothered Washington throughout the war was the presence of the prison ships that the British kept in the East River, filled with Americans that the British had taken prisoner. The people on the ships became known as the Prison Ship Martyrs after the revolution; all told, an estimated 11,000 men and women were left to die on the British prison ships in Wallabout Bay, the cove off today’s Brooklyn Navy Yard. The first prisoners put on the prison ships were the survivors of the Battle of Brooklyn, and after that various prisoners from all over, as well as, presumably, citizens who refused to take a loyalty oath. More people died on the prison ships than died in all the battles of the entire Revolutionary War.

If you were an officer, or had any economic wherewithal you could buy your way off the prison ships. If not, you died there. Many are thought to have been black slaves who fought on the American side (even though the British offered them their freedom if they fought for the British side); others were average soldiers, as well as sailors taken off privateers. In the early 1800s, when businessmen raised money to build the statue of George Washington that now stands on Wall Street, Tammany Hall asked why there wasn’t a monument to the Prison Ship Martyrs, as the bones were still washing up on the shores of Brooklyn for many decades after the war.

Today the bones are interred at Fort Greene Park in a crypt, beneath the beacon-like obelisk designed by Stanford White, put in place after Walt Whitman began a campaign for a monument. Every year, there is a ceremony there, commemorating them. I have read recently that there also will be a beacon on the top of the new World Trade Center tower. It is the part of the building that will bring it to a height of 1,776 feet. On September 11th, 2001, people in the area of Fort Greene Park went to the top of the park to watch the old World Trade Center towers as they burned and eventually collapsed. It seems to me that some places are always important to us. We go to certain points in our home landscapes over and over, to help us strategize, to find protection, to try to find a way to understand.

Previously: The Landing In New York, Scouting Old Locations, The General And The Moose, The Battle Begins, The Mystery Of The Missing Marylanders’ Graves and The Amazing Evacuation

Robert Sullivan is the author of a several books, including Rats, How Not To Get Rich, and The Meadowlands. His newest book My American Revolution will be published Sept. 4 (next Tuesday!) and is available for preorder.