An Analysis of the Thomas Kinkade Calendar for May and June

by Drew Dernavich

Well, this is awkward. But before we start, let me say: R.I.P. Thomas Kinkade, who died last month. While all of the circumstances surrounding his later life and sudden death may never be fully known to the public, it’s clear that he was carrying some demons in addition to his talent and ambition. It’s also clear that his painting had become an effective way to mask those demons. Thomas Kinkade the Message was supposed to be the proxy for Thomas Kinkade the Man, but Thomas Kinkade the Marketer overruled them both. But while he’s gone, his monthly calendar is still a thing, and so, yes, this column is still a thing.

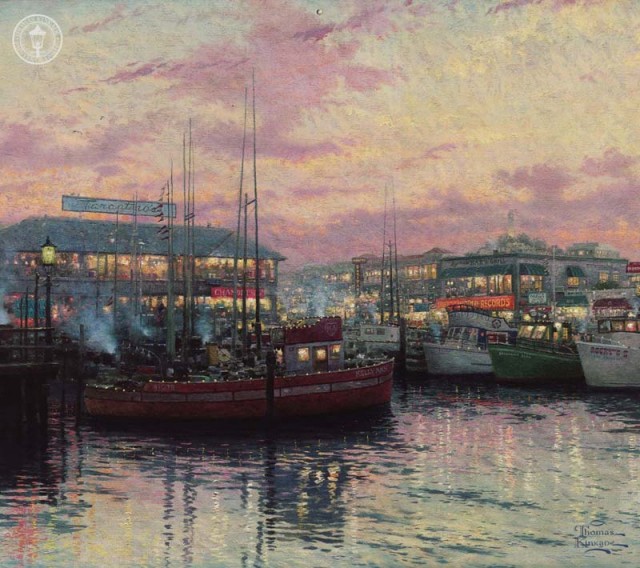

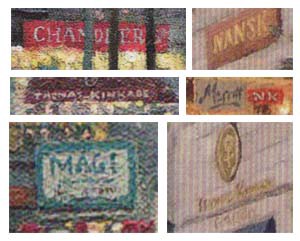

May and June are similar months, thematically: they’re about commerce. It’s interesting, whenever Kinkade “shares the light of faith and hope” he goes all gauzy and superficial, but he’s remarkably direct when it comes to painting a scene of business. So here we have San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf and Carmel’s Ocean Avenue, and in both we have the typical just-after-a-gentle-rain shimmer and the “golden hour” pre-sunset sky (one looks like it has been copied and pasted from the other), but your eyes are mainly directed to what could be called “sharing the blazing light of retail.” Will we ever discover that ConEdison or Pacific Gas & Electric were his investors? Many of the stores bear the names of his family members, his wife Nanette (also NK and NANSK) and daughters Merritt and Chandler, and in both paintings we see — wait for it — a Thomas Kinkade retail store. Why, we never knew! It must have crossed Kinkade’s mind to create an infinity mirror effect, depicting his Carmel gallery pictured in a Carmel street scene hanging on the wall inside the Carmel gallery, and on and on. It’s likely that the bristles were not small enough, not that the ambition was not big enough.

To top it off we also see a man intended to be Kinkade himself doing “plein air” painting, as well as the name of the company he founded, MAGI (Media Arts Group, Inc.). Can we say the demons are in the details? There’s a theory that Jackson Pollock cleverly disguised his full name inside “Mural,” one of his essential paintings, highlighting the notion that behind the wild abstraction there is still a conventional structure to his work. To me, the gesture seems dubious at best, but the link between our “humble” illuminator of light and the man whom he condemned as creating a “culture of chaos” is interesting. Chaos is as chaos does, right? Even Michelangelo, who famously carved his name across Mary’s sash so that everybody would know the Pietá was his work, didn’t write “check out my other work” or “I’m available for commissions!” Commerce is as commerce does. The spotlight of self-promotion shines above Kinkade’s fuzzy landscapes like the Bat-Signal. It’s the thing that grounds his work squarely in the modern era he claimed to detest.

Speaking of commerce, the choice of Fisherman’s Wharf is an apt one as a metaphor for Kinkade. Economic and technological changes have meant that the wharf is no longer a hub for fleets of fishing boats, but is a lovely tourist magnet with romanticized remnants of bygone eras. Sound familiar? When you order fresh fish at a restaurant, you may get either freshly caught fish or, wink-wink, freshly defrosted fish. But it’s, you know, fresh enough. Kind of like how a mass-produced canvas print of a Kinkade painting, if dabbled on by a “master highlighter,” can still be considered an original, or at least original enough.

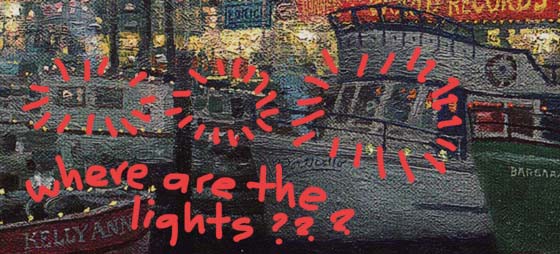

And I may be wrong, but I think I noticed an error in the wharf painting as well. There is a boat in the middle that appears to not have its lights turned on. What happened? Is there a dark subplot here? Are there teens playing strip poker inside? Is this the home of the scoundrel who removed all the humans from the painting? Did Kinkade run out of the color 80-Watt Fluorescent? Disappointingly, this is only oversight and not intrigue. We know that in Kinkade’s fantasy world the light, whatever it meant, had to be coming out of everything and everywhere all at the same time. He never was able to break out of that world. Maybe the more apt metaphor is not Fisherman’s Wharf, but Alcatraz.

Previously: January, February, March and April

Drew Dernavich is a cartoonist for the New Yorker magazine (not that cartoonist — the other one) and the co-creator of the cartoon improv show Fisticuffs! He is on Twitter.