An Analysis of the Thomas Kinkade Calendar for January

An Analysis of the Thomas Kinkade Calendar for January

by Drew Dernavich

“Formulaic.” “Schlocky.” “Tremendously successful.” These are some of the epithets that are routinely directed toward painter Thomas Kinkade by the cultural elitists in the current art and media establishments. But has anybody really taken a deep look at Kinkade’s work? You can dismiss his work as cheesy sentimentalism, but hey — can you name any other fine artist who has so thoroughly dominated the intellectual territory between Lids and Things Remembered? I didn’t think so. In an effort to plumb the complexities of Kinkade’s work, each month I’ll be discussing a page from his 2012 “Painter of Light” calendar. Let’s start with January, the month that Kinkade — slyly — has chosen to lead off with.

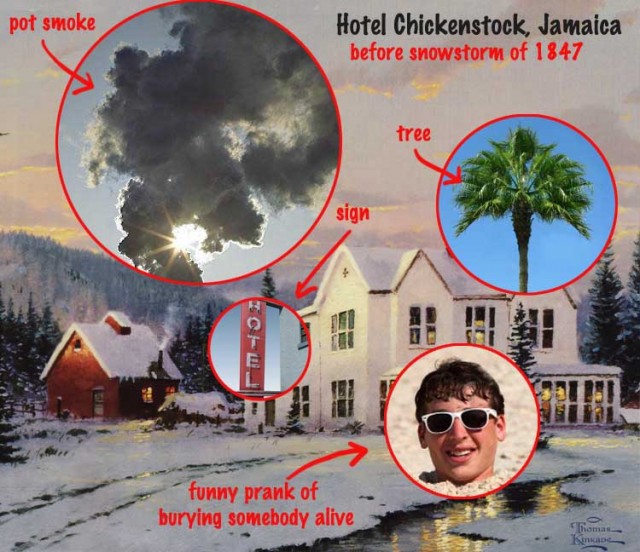

At first glance, January’s painting looks like a clichéd Currier & Ives-type ripoff: a sleepy New England cottage on a peaceful winter day. But this is no cliché. If you look closer you’ll see that this is, in fact, a scene from beachside Jamaica, specifically, the legendary Hotel Chickenstock, in the aftermath of the deadly July snowstorm of 1847 which killed thousands. Kinkade here has captured this disaster in all its horrific detail, despite the fact that absolutely no historical records of this event exist. A naïve critic would say that he has whitewashed all humanity from the picture, but this method is exactly how Kinkade invites us to participate in this human tragedy: by choosing not to paint a single person in the frame. No footprints, no tiny silhouettes, no stray fast-food wrappers — nothing anywhere to remind you of an actual human being.

Kinkade lets the painting do the storytelling, but I’ll give you some clues about the sources he’s drawn on for the imagery. Here I’ve taken photographs of the actual location and superimposed them on top of the painting. As you can see, the artist is not interested in sparing viewers’ emotions. The snow has stripped the hotel sign from the side of the building and flattened the palm trees into triangle shapes. Wintery weather has covered both the beach and the beachgoers, turning the shoreline into a graveyard. A young man whose drunken vacationing friends buried and left him to die in the sand, which is a hilarious prank, is now left to die in the snow, which is still pretty funny but less so. And with the musicians in a deep freeze, the volcano-like cloud of marijuana smoke which daily poured out of the recording studio next door was reduced to a wisp. This was the day that reggae music died (it came back again, as you know, so no worries).

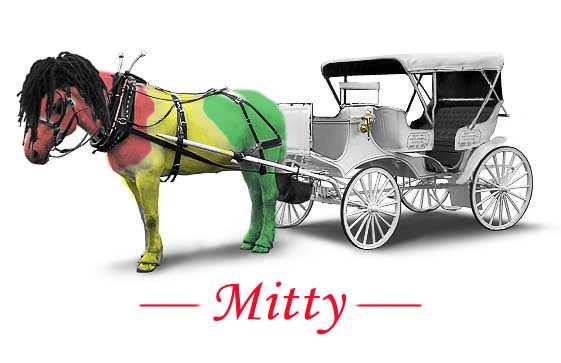

Lastly, Kinkade’s meticulous eye for detail is nicely in evidence here. The tracks in the foreground belong to the taxi carriage pulled by Mitty, the last of the island’s natively Rastafarian horses (the covering up of hoof prints being, again, Kinkade’s loving tribute to life). Everybody loved Mitty, but Mitty did not survive the storm. And this is a clear allusion to faith: the line “It was then that I carried you” from the “Footprints” poem was inspired by what everybody in Jamaica had said at one time in his or her life: “I was so insanely high from smoking weed and grooving to rocksteady rhythms all night that I must have blacked out, but when I saw those tracks it was then that I realized that somebody must have tossed me in Mitty’s carriage and said ‘take him to the Hotel Chickenstock.’”

Are you a Kinkade admirer yet? If not, there’s still time — we’ve still got eleven months to go.

Drew Dernavich is a cartoonist for the New Yorker magazine (not that cartoonist — the other one) and the co-creator of the cartoon improv show Fisticuffs! He is on Twitter.