When Exactly Did It Get Cool To Be A Geek?

When Exactly Did It Get Cool To Be A Geek?

by Jane Hu

In the final episode of “Freaks and Geeks,” the Freaks group leader Daniel Desario accepts an invitation to play Dungeons & Dragons with the notoriously geeky A/V club. Surprised by Daniel’s warm receptivity to the game, the Geeks wonders what this means for their future status. As Bill puts it: “Does him wanting to play with us again mean he’s turning into a geek or we’re turning into cool guys?” Sam answers, “I’m going to go for us becoming cool guys.” It’s a nice ambiguous note on which to end the show.

Outside the universe of “Freaks and Geeks,” a similar drift has occurred. Geekiness has accrued cachet, and geeks are becoming the cool guys. In an interview about the comedy web series “Geek Therapy,” actress America Young observed: “We started talking about how geek is ‘in’ now. Everyone, all of a sudden, was proudly waving their geek flag. How cool is it that traditional high school status had been turned on its head?”

An interesting thing about the name of Paul Feig’s show: When the words ‘freaks’ and ‘geeks’ first came into circulation, they were interchangeable; to be a freak was always to be a geek: an aberration, a spectacle, something to be gawked at. That said, who is and who isn’t a geek has been contested since the word’s first printed appearance, in 1876, and up through today, when the borders between ‘geek’ and ‘nerd’ are continually getting drawn, redrawn and then redrawn again. But if ‘geek’ always used to mean ‘freak,’ when did the two groups become (as suggested by Feig’s show title) separate, even opposed? And when did that magic moment occur when it became okay, even cool, to be a geek?

***

‘Geek’ makes its first printed appearance in F.K. Robinson’s Glossary of Yorkshire Words and Phrases with this definition: “Gawk, Geek, Gowk or Gowky, a fool; a person uncultivated; a dupe.” Parked there between “gawk” and “gowk,” geeks have always been, like freaks, positioned as a spectacle. Indeed, as everyone who loves Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love knows, for the first half of the twentieth century “geek” was used to describe carnival sideshow acts and circus freaks: specifically, the sort who bit the heads off live chickens. The performance of standing in front of a crowd, biting off a chicken’s head might be seen as the original — and quite explicit — embodiment of the notion of geek as other: no one asked those geeks if they wanted to maybe go out for coffee later, either. As Stephen Shiff notes in a 1995 The New Yorker essay

(sub. required) — the essay’s title “Geek Shows” a clear play on ‘freak shows’ — geeks of the time were sometimes even more marginalized than freaks, who “had been reduced to their spectacular status by terrible accidents of birth, whereas the geek’s calamity was entirely voluntary.”

Freaks and Geeks.

Freaks are Geeks.

Freaks = Geeks = Ultimate Outsiders

The beauty of Feig’s title for the show is how it puts the words on two opposite sides of the see-saw: opposed but on the same platform. As the show’s final episode hints at, freaks aren’t all that different from geeks, and both can be cool. But to pose freaks and geeks as cool is to move them from the outside to the very most inside — to the cultural and social center to which every normal person should aspire. As a phrase, ‘cool geeks’ is a contradiction in terms. But that’s not saying much. Since the meanings of ‘freaks’ and ‘geeks’ started to diverge in the 60s, the interpretations of ‘geek’ have grown hopelessly muddled.

Throughout the 80s, geeks became to replace other derogatory terms such as ‘square’ and ‘egghead.’ Geeks became detached from freaks only to enter other semantic wars, such as the one fought between geeks and nerds — one that seems (perhaps in principle) irresolvable.

An attempt to parse out the connotations of ‘geek’ and ‘nerd’ tosses one into a whirl of disputes (many of them rigorous and turning on subtle discrepancies). But for the most part, geeks have been associated with expertise, while nerds are afflicted with social ineptness. While some militantly police the borders between ‘geek’ and ‘nerd,’ others don’t observe the difference. Geeks and nerds tussle over who has claim to the always-expanding, ever-powerful tech culture (a group once seen as a hyper-specialized subculture, but who have come to increasingly define Culture, with a capital C, at large).

Throughout the geek v. nerd debates, many have maintained that be you geek or nerd, either way you just can’t be cool. As Steve Lohr, a New York Times technology columnist, writes, “a geek suggests a person with special expertise, while nerd suggests social ineptness. And neither are cool.”

“Special expertise” leads one to consider the myriad of geek subcultures: computer geeks, anime geeks, coffee geeks. Of course, being that he’s a journalist with specialized expertise in the topics regarding technology and innovation, the inference here is that Lohr himself might be something of a geek.

Then there’s “Freaks and Geeks” creator Paul Feig, who despite being a millionaire with a series of Hollywood successes to his credit, would be the first to assert his own uncoolness, as he did during this interview with a writer from The Guardian:

“Oh, I’m very nervous. I mean, you just don’t know, do you?” he frets, his dapper three-piece suit, lavender tie and matching pocket handkerchief unable to conceal his jitteriness. “I’m fighting against LA’s tyranny of the casual,” he says of his attire, with self-mocking defiance. But the reviews of Bridesmaids have been amazing, I say. He counters by reciting criticisms he claims were sprinkled through the praise (despite a thorough search later, I cannot find a single one of them).

As if all this weren’t enough to give his publicist a heart attack, Feig launches into a theory about why he’s “a failure.” This leads to him recounting the days “when I couldn’t even get a TV pilot made!” with such eagerness that one might think he was still a jobless hack, as opposed to someone involved in the best American TV of the past decade, including cult teen drama “Freaks and Geeks” (which he wrote), “Arrested Development,” “The Office,” “30 Rock,” “Bored to Death” and “Mad Men” (all of which he did directing stints on). “Well, it’s nice that people keep giving me a shot,” he concedes.

I, for one, think Feig’s claim to being “a pretty feminized geek” is utterly cool. But who am I to say? I’m just another geek.

***

But somewhere along the way, just like Feig, “Freaks and Geeks” itself became cool. These days, the short-lived production is a cult classic often invoked to signal one’s (arguably geeky) devotion to a once marginalized outsider, and underappreciated television series. The show’s a 9.2/10 rating on IMDB is just one marker of the wide admiration it now enjoys. The geeky show got voted Most Popular, and as it did, Feig’s show, as a cultural artifact, became one more example of how what’s geeky pivots on a hinge that swings between cool and un-cool so effortlessly that it’s often difficult to pinpoint which side our allegiances should lie if we are to remain at the popular kids’ table. Insiders are cool because they know something about the outside of the mainstream: this places them inside the inside, at the heart of cool. Geeks specialize and obscurity is often an indicator of their success. They know more. They know earlier. Hence they are cool.

It’s hard to pinpoint who was the original cool geek, but chances are this eminent First One had something to do with the Internet and, by extension, the information boom: Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Sean Parker (now forever represented in my mind as a particularly manic Justin Timberlake). Geeks are characterized by a drive and enthusiasm that, as set against the slacker culture of Feig’s Freaks, has returned as being incredibly powerful. And cool.

A 2010 Wall Street Journal article titled “How Steve Jobs Made Geek Culture Cool” claimed:

But these days, we’re all geeks. Everyone’s got an iPod, an iPhone or an iPad, and it seems the whole world eagerly awaits to see what Jobs will do next. […] Geek culture is a new counterculture — a world full of amazing products and films, music and games for people who are proud to be nerdy and square.

Being always one step off and one remove from the crowd is to the geek’s benefit. Being a geek affirms one’s sense of individuality — one’s special status — through being different. If the rest of the world is catching up, then the true geek is only going to try a little harder to be the first to adopt.

Geeks push envelopes. Slipping from the OED’s definitional radars, the current-day geek contains multitudes. The ‘cool geek’ can be intelligent and athletic. He can fix your hard drive, while holding a perfectly sociable conversation. These days geeks can even, goodness forbid!, be sexy. If power, which Kissinger assured us is the ultimate aphrodisiac, is sexy, then Silicon Valley geeks possess a lot of it. Having lots and lots of money probably doesn’t hurt either.

Popular entertainment has capitalized on the connections between geekiness and desire through television shows like “Beauty and the Geek” and “Geek Love.” That first show, a reality show promoted as “The Ultimate Social Experiment,” spins upon the logic that the possibility of romance among beautiful females and geeky males is a social challenge. Watching these figures move on your television screen, we’re supposed to wrinkle our brows because, yeah, beautiful people just don’t look like they belong with buttoned-up brains. But just as “Freaks and Geeks” once did, these shows strive to reconcile two socially and visually disparate groups.

Remember that first-ever, 1867 printed mention of ‘geek,’ which paired ‘geek’ and ‘gawk’? That definition shows the word literally emerging from a function of sight: “Gawk, Geek, Gowk or Gowky.” The geek evolves from the gawk to become the awkwardly gowky. The Cool may be the Beautiful (or at least the conventional idea of what that is), but they still see themselves as the physical antithesis of the Geeky, the to-be-gawked-at.

***

Equating seeing with knowing leads to mistaking seeing as knowing. In “Beauty and the Geek,” beautiful women struggle to reconsider their first impressions of gawky awkward men by recognizing the beauty inside the Geek. If we cut the link between seeing and knowing, what’s Beautiful and what’s Geeky no longer looks so clear-cut. What if we shuttle sight to the side? What if we try to see what’s on the inside? If on the Internet nobody knows what you are then they don’t know what you look like. When physical embodiment can be obscured, or misrepresented, or even cease to matter, we’re forced to reorient our communication tactics. (The trope of geek chic glasses conveniently emphasizes the sacrifice of visual clarity in the accumulation of knowledge.) If geeks are notoriously awkward in person, they are equally notorious for their fluency in the impersonal science of mediated, wired technology.

As Internet culture (and its facilitation of specialization and fandom) grows, being a geek is increasingly associated with knowing. In a New Yorker essay, music critic Alex Ross highlights how blogs and Internet culture genre nourishes the classical music geek: “If, as people say, the Internet is a paradise for geeks, it would logically work to the benefit of one of the most opulently geeky art forms in history.”

In The Laws of Cool, literary and technology scholar Alan Liu links cool with a capacity for knowledge: “Cool is a feeling for information.” This lexical association between “cool” and knowing, intuiting, or “feeling […] information” follows from communication theorist Marshall McLuhan’s division of technological media into the categories of “hot” and “cool.” According to McLuhan, interaction with “cool” mediums activated all of one’s senses, whereas “hot” mediums only triggered one sense — that of sight. Media is cool when it necessitates one’s fully active, stimulated, even erotic, engagement with a technology.

As extensions of ourselves — as the things that help us see and help us be seen — technologies are as sexy as the geeks that work them. “Let me further point out how ubiquitously the word ‘sexy’ is used to describe late-model gadgets.” So writes Jonathan Franzen in a New York Times essay about his “infatuation” with a new BlackBerry. Franzen continues:

… and how the extremely cool things that we can do now with these gadgets — like impelling them to action with voice commands, or doing that spreading-the-fingers iPhone thing that makes images get bigger — would have looked, to people a hundred years ago, like a magician’s incantations, a magician’s hand gestures; and how, when we want to describe an erotic relationship that’s working perfectly, we speak, indeed, of magic.

Gadgetry, the Internet, infinite information. It’s hot because it requires our participation. It’s hot because it begs an act of extension — of engagement and agency — from us, for our fingers on the screen. It’s hot because it’s cool.

Even the verb ‘to geek out’ (as opposed to the freaks who only ‘geeked’) implies an act or experience of excess. To geek out is to overdo it — to do it more and to do it better. More importantly for our ecology, to geek is to do it earlier. Being a geek is about caring, maybe even caring a little too much. If that’s what is currently perceived to be cool, I’m all for it.

Sponsored posts are purely editorial content that we are pleased to have presented by a participating sponsor, advertisers do not produce the content. This post is coming to you from MiO. Change your water. Change your day. What do you want to change?

Related: When Did The Remix Become A Requirement, Wikipedia And The Death Of The Expert and Free The Network

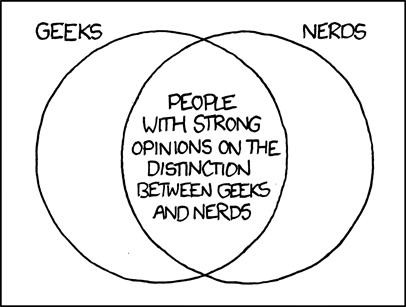

Jane Hu is our official correspondent for very recent history. Geeks and Nerds Venn diagram courtesy of xkcd.