How Much More Does Chinese Food Cost Today?

How Much More Does Chinese Food Cost Today?

We’re entering the Year of the Dragon. Last night was the beginning of the new lunar year, which makes today what we call Chinese New Year (and what they call in China, New Year). It may seem pat to take this occasion to discuss our relationship with Chinese food, and the relative expense of it over time, but it’s not meant to be. At feasts all over the world today, dumplings will be eaten for prosperity and noodles for long life. And while Americans use a different metric for determining what year it is, Chinese food is as mainstream in this country as French fries and buffalo wings (both of which are, as it happens, available at your nearest Chinese take-out).

So Happy New Year, and while we’re here, as it’s the purpose of this column, let’s examine if the chicken and broccoli dinner combo you snag on the way home from work costing you about the same that it would’ve cost your grandparents, or, as was the case with steak dinners, the adjusted cost has been inching up over time?

By the 1980s and ’90s, when many of us were growing up, Chinese food had pretty much fully integrated into America, no matter where it was that we were living, cities or suburbs. In the middle of a landscape defined by McDonald’s and Burger Kings, it was hard to find a place without at least one Chinese joint. Where I grew up, in the outskirts of Rochester, NY, my family’s go-to was a very nice place called the Golden Phoenix (hey, it’s still there!), where we had many a meal, both take-out and sitting down. For me, at least, the appeal was the variety it offered, as little of what was offered resembled the meat and potatoes (or Hamburger Helper, in some instances) that constituted daily fare. From the fried noodles and duck sauce laid out to start to the wonton soup to the cashew chicken, it was an array of flavors (the soy sauce, the ginger, the garlic) that never crossed our kitchen table except when served from the ubiquitous folded-paper bucket.

From the view of my folks who were actually paying for this, the meal was attractively inexpensive as compared to a trip to the steak house or the Italian restaurant. I was unable to hunt down an archived menu for the Phoenix, but to give an idea, in 1989, at Bamboo Garden in Washington, D.C., a pint of beef chow mein and an egg roll cost $4.50 (or $8.91, converted into 2011 dollars). And as recently as 2000 at Wong’s Garden in Long Island, an order of Roast Pork Mai Fun went for $5.95 ($7.77 adjusted).

Of course, my recollections are from the perspective from someone from a family of decidedly white Middle American roots. If you grew up in an urban setting, your access to Chinese food was more convenient than mine, and if you grew up in Chinese-American communities, as did my friend Hsin-Yi, who set me on a course of obsession with Chinese food a decade ago when she invited me to the Lunar New Year meal her parents throw every year, then perhaps hamburgers and fries were the exotic meal.

But these restaurants scattered across the country, and the Chinatowns that every sizeable town has, didn’t just happen — not there one day, and then there the next. It took some time, a good hundred years.

***

You may think that you know all you need to know about the story of Chinese food — it’s cheap, delicious and was brought here by emigrated Chinese. But an awful lot happened between the founding of the United States and now, when Crab Rangoon is as American as a steak dinner. (And actually, it is: Crab Rangoon, those cream-cheese wontons, is just one of many non-authentic dishes invented to cater to Western tastes, as dairy is generally not served in mainland China.)

Chinese cuisine has had to get past two things. The first thing is the idea that the food is somehow unclean, or, to be more specific, made with rats, cats or dogs. This taboo goes back to the first time Chinese food passed American lips, in 1784, when the crew of the Empress of China, loaded with ginseng made the passage. This was the first attempt by Americans (only very recently being called such) made to trade with China. China forbade entry by foreigners anywhere but a certain trading compound in Gwangzhou, at the headwaters of the Zhujiang River Estuary in Guangdong Province (just inland from Hong Kong). This compound, home to the traders of the world, was located near a local market, and amidst the edibles being vended, in with the livestock, were cats and dogs. So on the occasions when the American traders were feted with local food, they were of course a bit leery of the fare. And as noted by Andrew Coe in his book Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States, this was a commonly held perception:

In nearly every western description of Chinese food from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, this information is repeated: the Chinese dine on dogs, rats and cats. Some of this comes from doubtful texts, like the [anonymous work] the Chinese Traveler, but in other texts the information has enough detail to give it the ring of truth.

The ring of truth is there because it’s true, by degrees — rats, cats and dogs are served in certain regions of China, which is different than saying, “Your Chinese food is secretly made of stray poodles,” which is the party line I remember from when I was a little kid (one soon supplanted by the rumor that Wendy’s burgers were made of worms). I’ve heard of a few hollers in Kentucky where the local delicacy is squirrel brains, and I can’t say I’ve seen the family pet/vermin line crossed in any restaurant at which I’ve eaten. Vive la différence.

The second obstacle is one met by pretty much every immigrant culture, though for the Chinese it was exacerbated by the marked cultural differences: the patronizing stereotypes applied by the customer that would end up being “their new countrymen.” Although America is a country made almost entirely of immigrants, the Chinese were a bit more unfamiliar than the Irish and the Germans, as China, the world’s oldest country, had done a pretty good job of sealing itself hermetically from the rest of the planet. (Plus also: racism!) The strange customs of dress, the uniform hairstyle known as “queue” (shaved above the forehead, long, thin braid in the back) and the language totally absent any European antecedent made the Chinese pretty much the new kid in class, waiting to have his lunch money taken. Though this was not just a case of name-calling and saying mean things, and rose to violence and intimidation, by citizens and government representatives alike. This ugliness culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act, signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur, effectively freezing Chinese immigration for sixty years, from 1882 to 1943.

This obstacle was not so much overcome as it was tolerated as it incrementally diminished (think Mickey Rooney in Breakfast At Tiffany’s as a shockingly recent example), and even turned to account in marketing for the nascent Chinese restaurant industry. The pagoda, panda, the caricature of the smiling Chinaman, the rustic Chinese landscapes with a pagoda, a panda and a smiling Chinamen — the stereotypical images were embraced to advertise the food being sold, to attenuate the otherness.

The flip side of this marginalization was obsession: at the same time that Americans looked down on the Chinese as backwards and unmannered, the appetite for this alien culture grew. Returning missionaries in the late 1800s would embark on lecture tours, describing the mysteries of the Orient to rapt audiences. And as Chinese immigrants began to assimilate and disperse across the country, trappings of the culture — the fashion, the tableware, the knick knacks — were as lucrative a trade as the food.

Neither obstacle prevented the growth of the Chinese restaurant in America. After arriving in the 1860s seeking fortune during the Gold Rush, by the turn of 19th century into the 20th, Chinese restaurants were scattered across the country, as most evident in the urban neighborhoods in which Chinese immigrants settled, which became known to everyone else as Chinatowns.

***

As these Chinatowns were developing, Chinese food was enjoying its first surge of national popularity, thanks to a dish of disputed origins: chop suey.

The story goes (and is sometimes disputed) that Chinese statesman Li Hongzhan travelled to America in 1896, a goodwill visit of sorts. The trip lasted only a week, but was widely covered by newspapers. After a banquet of classic French food at the Waldorf in New York, it was reported that Hongzhan, after eating sparingly of the Western food, requested and ate a meager order of chop suey prepared by a chef that was a member of his entourage. Somehow, as this account hit the papers, the American imagination was affected, and for decades after it became fashionable for the Bohemian set to seek out Chinese eateries for this mysterious and exotic chop suey — a stir fry of meat and vegetable (including bean sprouts, exotic at the time), in a brown gravy. Chop suey even became immortalized in popular music, as performed by Louis Armstrong and Prima. Chop suey was a craze.

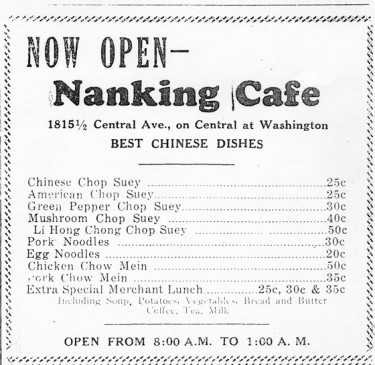

In 1931, you could drop by the Nanking Café in Los Angeles, where a plate of Li Hong Chong Chop Suey cost $.50 (or $7.40, adjusted for inflation). In 1943 you could dine at the much more formal (full bar!) Forbidden City in New York, where the Li Hong Jan Chop Suey (made with Virginia ham and a clear reference to the statesman mentioned above) cost $1.75 (which comes to $22.75 in 2011 dollars). And back to LA in 1955, Joy Luen Low was still serving the Li Hong Chong Chop Suey, for $.85 ($7.13 adjusted).

(Do note that by this era, a bifurcation of sorts was happening, as upscale locations like Forbidden City catered to an upscale dining crowd, while less fussy establishments like the Nanking Café specialized in more of a take-out business.)

However, it turns out that chop suey may have been less than authentic, if not an outright expedience in finding a way to broaden the appeal of these new Chinese restaurants. Chop suey in Mandarin would be za sui, or little bits, and at the time it was thought to be an authentic peasant dish, transported seven thousand miles to these shores. But in tracking this down, NYT reporter Jennifer 8. Lee (in her book The Fortune Cookie Chronicles: Adventures in the World of Chinese Food, which is pretty invaluable on many of these topics) comes to the conclusion that not only is the Li Hongzhan story probably apocryphal (i.e., the reports did happen but were maybe exaggerated), but that the true origin of the dish was a Chinese restaurant serving up bits of what was left in the kitchen and accurately describing it as za sui, which to American ears sounded a lot more appealing than leftover hash.

***

In the late 20th century, some characters, likely and unlikely, insert themselves into the story of Chinese food in America. And while none are directly responsible for you growing up eating moo shu pork, Craig Claiborne, President Nixon and Misa Chang certainly helped.

First came Claiborne, the famous food page editor for the NYT, so integral to developing what we now think of as food journalism from 1957 on, who gave legitimate, mainstream attention to Chinese restaurants such as Mandarin House, where, in 1965, an egg roll followed by an order of roast pork lo main would set you back $2.90 (or $20.71, in 2011 dollars). Claiborne’s reviews also helped propel Shun Lee Palace, opened by Chef T.T. Wang and partner Michael Tong in 1971 on East 55th Street, into the realm of respected midtown restaurants. Shun Lee Palace, which, like Mandarin House before it, introduced non-Cantonese dishes, unrepresented up until then by Chinese restaurants (such as Szechuan at Shun Lee), later moved and reopened as Shun Lee Dynasty and in 1974 became the first Chinese restaurant to be awarded four stars by Claiborne and the New York Times.

At roughly the same time, 1972, Nixon went to China. It may be difficult imagining Richard Nixon inspiring anyone to eat something, the trip was unprecedented politically, and was covered with the intensity usually reserved for moon shots and royal weddings (or, to translate to modern terms, for everything ever, all the time). Direct negotiations with the Chinese were important historically but when President Nixon and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai shared a Chinese meal on live television, it was the best advertising for Chinese restaurants that money couldn’t buy. According to Coe: “People were swarming to classes in Mandarin and in Chinese cooking; department stores sold Chinese handicrafts (the Mao suits quickly sold out at Bloomingdale’s in New York).”

Claiborne and Nixon you’ve no doubt heard of. Misa Chang is, however, as successful as either, and perhaps has made the most lasting contribution, as she claims to be the person who invented the Chinese take-out industry. Chang’s chain of restaurants, Empire Szechuan, are somewhat a New York City fixture, especially in the Upper West Side, where Chang opened the first Empire Szechuan in 1976. Takeout was already a common attribute of Chinese restaurants, but, after a couple weeks of slow business in a then-sketchy neighborhood, Chang figured that bringing the still-hot food directly to the door would be a service that would goose the business. Which it did: at first, she delivered herself, and shortly she hired what would be the first Chinese delivery man, now as omnipresent as taxicabs. (The Empire family of restaurants persists, by the way.)

The other of Chang’s legacies, very familiar to urban residents, is the proliferation of takeout/delivery menus, on stoops, under apartment doors, in building vestibules. The problem for restaurants that began to deliver was one of advertising: if the target customer was one that was adverse to leaving the apartment, how then to let them know that dinner is a phone call away? So then delivery men, in the course of their travels, would bring with them spare menus, which they would put wherever they could. Eventually, delivery men would devote their mornings to scattering menus and their nights to delivering food. By the 1980s, this culminated in a kerfuffle, with NYC residents angry at the clutter of unwanted menus and delivery men just doing what the boss told them to do. Some fistfights and lawsuits resulted — Empire paid some fines to the city, and one resident was jailed for sixty days for an altercation with a delivery man over menu deployment. The issue has never been resolved to anyone’s satisfaction, as every couple years a city councilman will propose a ban on menus, and the variations of the NO MENUS signs on doors remain to this day New York’s special rainbow of Seinfeld-ian annoyance.

A representative menu from the time is this one from the Kips Bay location of Hee Seung Fung from 1977. When the chicken chow mein combination platter showed up at your door, you would give the delivery man $2.50 ($9.28, adjusted), plus a nice tip, I’d hope.

***

And that brings us back to now. Just the other night I chose a random Chinese restaurant in my neighborhood, New Hong Kong House on Cortelyou Road in Brooklyn, and ordered myself a combination platter of Chicken Lo Mein (with egg roll and pork fried rice!), which cost me $6.95.

So then, let’s consult the handy Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index calculator and see how things add up, giving each of the prices in 2011 dollars. (Note that the CPI gizmo has not yet updated to 2012 dollars, so we are looking at prices in last year’s money.)

1931: (Nanking Café) $7.40

1943: (Forbidden City) $22.75

1955: (Joy Luen Low) $7.13

1965: (Mandarin House) $20.71

1977: (Hee Seung Fung) $9.28

1989: (Bamboo Garden) $8.91

2000: (Wong’s Garden) $7.77

2012: (New Hong Kong House) $6.95

Now that’s a confusing mix, with spikes in the odd years of ’43 and ’65. But do remember that each of Forbidden City and Mandarin House were big-R restaurants that fed a more well-heeled clientele than the place down the corner with the bullet-proof glass. So if we pull those out, we get a pretty consistent price range between seven and nine dollars, with the lowest price coming this year.

And of course there are too many variables to make this anything approaching scientific, whether you take into account the geographic dispersion of the representative restaurants, or the haphazard variety of menu items (which I, in good faith, tried to make as regular as possible), or the criminally small sample size. Also note that I deliberately avoided the recent trend of all-you-can-eat Chinese buffets that are popping over the past decades, as I’ve seen too many dust-ups over who gets the last cluster of snow crab legs. But looking at this, I would suggest that our Chinese food, perhaps the most unifying cuisine in the country given its uniformity and appeal, has proven to be immune from inflationary/deflationary factors. Affordable, even. Not to mention delicious.

Previously: Books, Barbies, Televisions and Steak Dinners

Brent Cox is all over the Internet.

Photo by xtopher1974, via Flickr.