Mock Goose And Other Dishes Of The War-Rations Diet

by Stephany Aulenback

There is a website, called The 1940s Experiment, whose proprietor, Carolyn Ekins, who was born and raised in the UK but now lives in Canada, is attempting to lose a hundred pounds by following a wartime rations diet, specifically made up of the foods eaten by the British public during World War II. For every pound she loses, Carolyn will recreate one authentic wartime recipe and post about it. She has already posted recipes for Mock Goose (made with lentils), Potato and Carrot Pancakes (“delicious”) and an Eggless Fruit Cake (“looks curiously like meat loaf”), among many others. Carolyn has attempted — and succeeded at — this type of diet before; in 2006, she lost 57 pounds following the diet. This time, about six weeks in, she’s lost around 25 pounds.

The term “rationing” does not usually bring to mind images of glowing health, but rather horror stories like the one found in Dangerous Muse, a biography of the writer Lady Caroline Blackwood, who was an heiress to the Guinness fortune and wife to both painter Lucian Freud and poet Robert Lowell (although not at the same time, of course). When she and her two siblings were small during World War II, one of their nannies ate most of the children’s rations herself. Caroline and her sister were saved by school lunches; their younger brother Sheridan, not yet in school, used to have to beg for food from the tenants of his parents’ estate and suffered from malnutrition as a result. (To say that Lady Caroline’s mother, Maureen, the Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, was not an attentive mother is a gross understatement. Their father, who presumably might’ve noticed that his children were starving, was away at war.)

Rationing was introduced in 1940 and did not fully end until 1954, and anecdotes like Blackwood’s can be found in abundance in British memoirs, fiction and historic writing about the period. This fascinating article by Diane Duane, for example, explains how C.S. Lewis’s experiences under rationing may have influenced his writing about food in the Narnia books:

[T]he first sense you get in Narnia about Lewis’s attitude toward food is an air of profound nostalgia for the lost paradise of a varied, ample diet, and a willingness to wallow in the nostalgia somewhat. The very first meal any human experiences in Narnia, the high tea which Mr. Tumnus serves Lucy in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, is a perfect evocation of a turn-of-the-century British tea. Nor is this the hotel-based “high tea” concept, with tinkly china and multiple fancy pastries, but the middle-class tea you would properly have in someone’s home, a meal rather than a snack, long on protein, carbs, and comfort. For Lucy, briefly escaped from the middle of the war, and for Lewis, who was as hungry as anyone else in Britain and (some of his letters reveal) as bored by the limitations and substitutions of wartime food, this meal would have smacked of Heaven. It would be years before any Oxford don or little English girl could sit down to the delights of a meal that featured fresh eggs and real sardines, a meal in which there was butter for the toast, and actual honey, and cakes with sugar on them. Among Lewis’s letters are a number of lyrical thank-you notes to friends or fans who sent him “care packages” of meat and other delicacies from the U.S. And elsewhere. So we can hardly blame him for indulging his longings a little in the world he was starting to invent.

And if ever you’ve read (or watched) 84 Charing Cross Road and enjoyed the pen friendship between Helene Hanff, a writer based in New York, and Frank Doel, a London bookseller, look again: in large part their bond developed because Hanff frequently sent gifts of meat and eggs to Doel’s bookshop to be shared among the employees. Indeed, rationing is mentioned almost immediately, in the fourth letter from Hanff to the bookshop, dated December 8, 1949:

Brian [a British friend of hers] told me you are all rationed to 2 ounces of meat per family per week and one egg per person per month and I am simply appalled. He has a catalogue from a British firm here which flies food from Denmark to his mother, so I am sending a small present to Marks & Co. I hope there will be enough to go round, he says the Charing Cross Road bookshops are “all quite small.”

Hanff may have misunderstood or exaggerated the severity of the rations for comic effect (rations allowed one egg per week), but all the same, they were hard to live with, and the bookshop’s employees were overjoyed to receive her gifts. As Doel said in his reply, “[E]verything in the parcel was something that we either never see or can only be had through the black market.”

While rationing and food shortages presented real hardships, the war created jobs for many British people put out of work during the UK’s Great Depression (aka the Great Slump). As the writer of this remembrance of wartime rationing notes, after “the long, desperate years of the Great Depression” for those now with jobs and incomes “food rationing, despite the restrictions, may have felt like a ‘leg up’ after years of deprivation, having to make do on hand-outs or soup kitchens.”

And surprisingly, a number of studies have shown that the health of the British people under wartime rationing was excellent, especially in the countryside, where many locally grown fruits and vegetables, which were not rationed, were readily available. Most of the more exotic, and hence imported, fruits, such as bananas, did become almost completely unavailable — on the rare occasion the odd one did manage to wend its way to Britain, it might have been auctioned off. Oranges, rare and precious, were reserved for children. Children at that time were actually much healthier than they are today. This makes sense because it was meats, fats, and sugars and processed foods — the kinds of foods at the root of many of the health problems we suffer from today — that were most strictly controlled.

When I emailed Carolyn to ask about her diet, she said that this was what caught her eye when, because of a prior interest in austerity, frugal living and back-to-basics lifestyles, she started researching how people in Britain ate during the war. “I began to devour recipe books by Marguerite Patten OBE, an English home economist, food writer and broadcaster. During World War II she worked for the Ministry of Food and did her bit to win the war on the home front by suggesting nourishing and inventive recipes using food rations. … The more I read, the more I became convinced that getting back to a basic, healthy diet with much less animal proteins, dairy and fats, no processed foods and plenty of fresh vegetables and fruit would be the way to change my life forever.” (Patten’s many, many cookbooks include Spam The Cookbook and the wistfully titled We’ll Eat Again.)

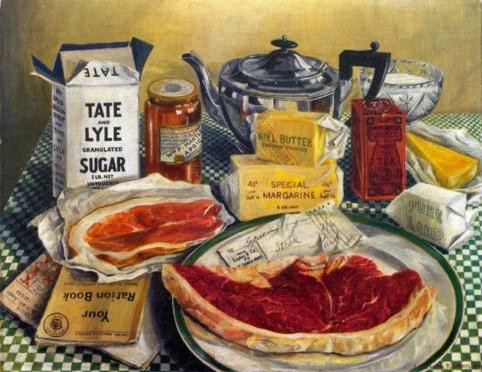

According to Carolyn, these were the rations for one adult for one week (except where noted otherwise):

Bacon & Ham 4 oz

Meat to the value of 1 shilling and sixpence (about 1/2 lb minced beef)

Butter 2 oz

Cheese 2 oz

Margarine 4 oz

Cooking fat 4 oz

Milk 3 pints

Sugar 8 oz

Preserves 1 lb every 2 months

Tea 2 oz

Eggs 1 fresh egg per week

Sweets/Candy 12 oz every 4 weeks

Fish was not rationed, although it became difficult to find.

This painting by Leonora Green shows a week’s rations for a family in 1941.

Along with the strict reduction in meats, fats and sugars, the intake of whole foods (as opposed to processed food) marks a significant differences between a wartime rations plan like Carolyn’s and the usual modern diet plans: “I’ve attended many well recognized diet clubs over the years in my hope of curing my food addiction,” she told me. “And do you know what I found? Most were promoting their own convenience food products or recommending processed convenience foods … food that had been tampered with, that had added chemicals that are hard to pronounce. (Trust me, that isn’t a good sign.)”

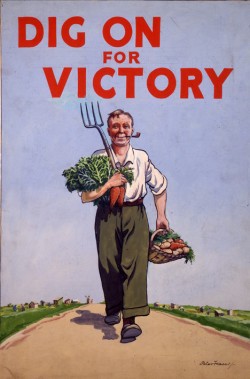

Carolyn was quick to point out that the plan she follows mimics the eating of those fortunate enough to have gardens in the British countryside or good access to one of the urban gardens that sprang up at the time: “People were encouraged to ‘dig for victory’ and flower beds and gardens became vegetable gardens or small urban farms as people grew lots of fresh vegetables, kept chickens and rabbits to supplement their rations,” she said. “I am in a way eating how I would have done during the war with a large productive back garden as a very large portion of my diet is plant-based, especially at the moment as I have turned vegan for 60 days to experience how vegans coped.”

For a 2007 Daily Mail article, a family with four kids lived on rations for a week. The piece noted that, while cooking with vegetable fats, like olive oil, is more healthy than the animal fats (i.e., lard) used during rationing, the diet was otherwise well balanced.

But even with good access to a variety of fruits and vegetables, surviving on rations was extremely difficult. And Carolyn admits that following this wartime diet in a modern environment can be challenging, too: “It can be incredibly difficult in those early weeks as your body adjusts, and getting used to cooking from scratch with limited supplies is challenging.” Dee Brooker, the mother featured in the Daily Mail article, also found the preparation of the food a challenge: “Meals normally take me about 30 minutes and while I really enjoyed cooking from scratch and the fact that I could see exactly how much salt, sugar and fat we were eating, it all took so long. One day I spent five hours chopping and preparing food and I was tied to that cooker for two to three hours most days.”

For Carolyn, one benefit of her 1940s experiment is it helps to keep the boredom that comes with ordinary dieting at bay: “I have approached this as a dietary social experiment. Were home front recipes during WWII absolutely ghastly? What did they really taste like? I found the names of recipes like Mock Goose & Lord Woolton Pie fascinating and needed to find out for myself what our grandparents and parents really ate. So losing weight by attempting to live 100% on a wartime diet was also a lesson in living history for me.”

Of the wartime recipes Carolyn has made to date, she says the cottage pie has been one of the best; the recipe, which made enough to feed her entire family, uses what would have been a week’s rations of minced beef for two people. She also recommends the sweet bread and apple pudding, which would’ve used up the rations for two ounces of butter or margarine, two ounces of sugar and one egg. Not-so-successful recipes have included one for curried carrots (“even Spam is better”) and one for mock cream that had a “gritty texture” and, disappointingly, “tasted nothing like cream.”

Related: The Vicious Trademark Battle Over ‘Keep Calm And Carry On’ and “Are You Airminded?” The Slang Of War.

Stephany Aulenback lives in Nova Scotia with her husband and two children. She blogs at Crooked House.