"Are You Airminded?" The Slang Of War

by Jane Hu

“Airmindedness” is a term that used to be everywhere and now it’s nowhere. The word, as defined by the OED, means an interest in and enthusiasm for the use and development of aircraft. The expression emerged with the development of the airplane in the early twentieth century, during which an entire generation struggled to expand their conceptual boundaries skywards. Prompted by the invention of mechanical flight, this airminded cultural moment was sustained by the military incentives that ceaselessly pushed for improvements to air power.

As media critic Friedrich Kittler proposes, technologies repeatedly find their ancestry in the mouth of war: “war was called the father of all things: it was supposed to have been responsible (borrowing loosely from Heraclitus) for most technical inventions.” For Kittler, all technology begins as war technology. Whereas contemporary and commercial uses of machines obscure their military roots, languages face similar signifying concealments. Expressions such as “airminded” disappear from the vernacular as they decrease in culturally potency, or are reinvested with new meaning. “Trench coats,” for instance, initially referred to coats worn by soldiers in the trenches, while “going over the top” once pointed to the moment when British soldiers crossed the parapet that separated trench from no man’s land. “Airminded” is just one significant example of how war and its accompanying innovations have always shaped how we speak.

***

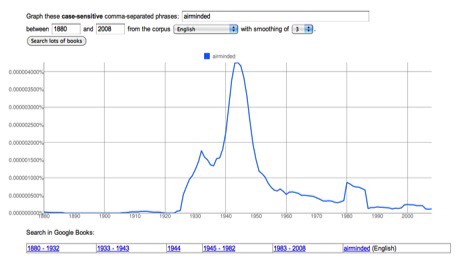

A search for “airminded” on Google’s Ngram Viewer yields the following graph:

The rise of the expression began around 1926 and hit a peak near 1945, around the end of World War II. Known as the war that radically and violently expanded the range of air warfare, World War II is unsurprisingly the period where “airminded” most infiltrated printed matter.

While the invention and fetishization of the airplane began in the 1900s, its take-over of, at least, the American and British imagination occurs closer to the mid-century. In this, the Ngram reveals its geographical limitations. (In reality, aerial bombardment began as an exclusively colonial technique beginning as early as 1911, but the likely airmindedness experienced by Tripolitan, Indian, Egyptian, Somaliland, and Afghanistan communities are not reflected by the graph.)

The Second World War might be viewed as the apex in the development of aerial technology, but even World War I hardly saw a period of peaceful sky. In The Great Air War, Aaron Norman notes that the bombing of cities began mere weeks into the war, when a German dirigible dropped 1,800 pounds of shrapnel bombs over Antwerp. Paris was bombed three days later. In his essay Air War Prophecy and Interwar Modernism, literary scholar Paul Saint-Amour lists the following incidents:

Between 1914 and 1918, bombs dropped from airplanes and airships by both sides killed more than 2,000 people and injured nearly 5,000 others. German zeppelin and bomber raids on London between May 1915 and May 1918 set 224 fires, destroyed 174 buildings, seriously damaged 619 more, and caused total damages in excess of £2,000,000.

In July 1917, Lovat Fraser wrote in the London Times, “If I were asked what event of the last year has been of the most significance to the future of humanity, I should reply that it is not the Russian Revolution, nor even the stern intervention of the United States in a sacred cause, but the appearance of a single German aeroplane flying at high noon over London last November.” Surely, airmindedness had begun to touch people’s imaginations even before the archival resources of the Ngram indicate.

***

Nonetheless, the prevalence of “airminded” during the war years is indicative of how increased aerial activity demanded new phrases and concepts with which to comprehend the sky. In La Machine de la Vision, urban theorist Paul Virilio describes airmindedness as a general cognitive overhaul brought on by war technology: “1914 was not only the physical deportation of millions of men to the fields of battle, it was also, with the apocalypse of the deregulation of perception, a diaspora of another kind, the moment of panic in which the American and European masses no longer believed their eyes.” Writing in 1988, Virilio does not invoke the exact word “airminded” (the expression having fallen out of vogue decades prior), but the implications are all there. Where masses no longer believed their eyes, they sought to understand their war-torn environments via slang, colloquialisms and euphemisms that saturated the cultural ether. “Airminded,” for instance, appears in newspapers and periodicals under a myriad of connotations.

Cultural preoccupations begin before their entrance into public print. The OED lists the first documentation of “airminded” in a February 26, 1927, London Times article on “The Norfolk and Norwish Aero Club.” The article itself indicates the prior prevalence of aerial interest: “The growth of flying clubs since the Air Ministry first arrange to subsidize six clubs 18 months ago is most encouraging, for they offer one of the most economical and direct ways of making the nation, in the words of Sir Samuel Hoare, ‘air-minded.’” (Like “week-end,” “air-minded” began in its hyphenated form — a piece of casual slang as well as stilted, literal description.) While many citizens wrote letters censuring such enthusiasm for the airplane, London publications were, on the whole, ready to promote a pro-air outlook.

Airminded “news” also followed the lines of poorly veiled propaganda. Periodicals like The Pennsylvania Medical Journal and The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review asserted that the airminded spirit was essential in good nurses. Naturally, only the airminded would be assumed to work in an airport.

In 1931, the London Times published a six-article series titled “Why Don’t You Learn to Fly?” Due to its popularity, it was reprinted as a little booklet free to anyone who asked. “The purpose of the articles was to help in the process of making Great Britain more air-minded,” the London Times stated in a subsequent issue, “We believe that the technical and economic aspects of flying are far ahead of the national psychology on the subject, and that the two need to be brought into adjustment by the people of this country developing more practical interest and confidence in flying as a form of travel and a form of sport.” Flying is fun! Don’t be scared. Aviators would even take those sufficiently airminded enough for a short spin between towns — an experience known then as “barnstorming.” With increased exposure to aerial technological, one might finally embrace flight as a thrilling component of modern life.

***

Despite widespread journalistic endorsements, getting on an airplane demanded more faith than many were willing to offer.

The April 13, 1929 edition of The New Yorker included a piece of short fiction by Alice Frankforter titled, “The Airplane Ride.” Published just a few years after the emergence of America’s first airliner, Frankforter’s story opens with a sentence that unexpectedly downplays the novelty of flight: “The light-hearted suggestion that you all drive over to the aviation field.” The sentences continue like this. Clipped. Lacking predicates. Fragmented phrases that command and demand one’s discomfort. “The Airplane Ride” both exposes and mocks the anxieties of “you,” the 1920s readership, the inexperienced airplane passenger. As though mimicking accelerated flight, the terse story transports readers from its initial “light-hearted” takeoff to a doubt-filled landing. “The thrill that is two-thirds pure terror,” writes Frankforter near the end, “The grim determination to enjoy this ride if it’s the last thing you do.” Such harsh and curt direct addresses rhetorically simulate the uncanny alienation people felt regarding air travel during the early twentieth century.

In the 1930s, few people accurately comprehended the degree to which the air power had advanced. As evinced in Farebrother’s story, one approaches, at best, the airplane with a “grim determination to enjoy this ride if it’s the last thing you do.” And that’s being positive. For many, flying was viewed as life threatening. To be fair, there were then few government regulations for either the carrier or the pilot. Most machines flown immediately following the World War I were surplus from battle.

Only near the end of the decade did airmindedness blossom as a phenomenon of mass culture. Saint-Amour observes that, by the late 1930s, premonitions of the next war had saturated public dialogue in Europe; the H. G. Wells and Alexander Korda film Things to Come (1936), with its opening scene of aerial bombardment, poison gas attacks and mass death in “Everytown,” offers only the most infamous example.

***

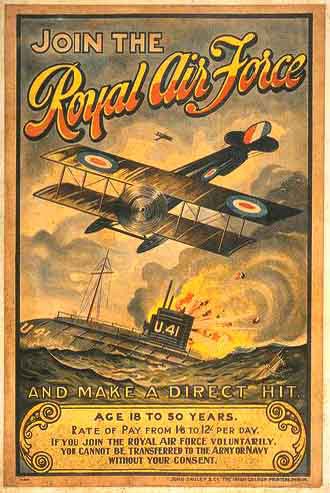

With looming threats of miliatary bombardment during the interwar period, mentions of airmindedness were largely future-oriented. The Ministry wanted young boys properly brought into the airminded fold. One British “Exhibition for the Modern Boy” was comprised of mainly airplanes. In America, Henry Arnold “wrote a six-volume adventure series for boys — based on the exploits of a young flyer named Bill Bruce — designed to raise ‘airmindedness’ and to create a favorable image of the “airman” for America’s youth. In the 1930s, boys’ aeronautic organizations flourished: the Junior Birdmen of America had no less than 500,000 members by 1936.” With preoccupations of technology and war, the first consciously airminded generation could not but fixate on how aircrafts might play into the plans and predictions of battle. As Tami Davis Biddle writes, the “development of aircraft in the early part of the twentieth century posed a problem of great significance to the military planners of all modern states. How were these new machines — as yet untested — to be integrated into existing military structures?” Thoughts of airmindedness are inextricably linked to wartime anxieties on the future and the threats therein. This pattern of fearing the advent of the ever-modern machine has, it seems, little changed since then.

With the rising acceptance of mechanical flight came a growing fear of the powers and efficiency of aerial bombardment. During the interwar period, exaggerations of air power hit a peak and, for many, the looming Second World War promised total annihilation. In the November 2, 1935 The New Yorker, E.B. White announced in his Talk of the Town column:

[I]t is our intention, from now on, to say something about flying machines every week. Aviation is the one subject to which we get an instant and violent response. Letters are still coming in, tearing us to pieces and gnawing at our entrails.

At the same time, for Londoners, the threat of the bomb became a widely publicized concern. As Tami Davis Biddle describes in her introduction to Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare, the increase of airmindedness throughout the interwar years lead to greater “claims about the power of bombers and the vulnerability of enemy societies” and “contributed to deep public anxiety about future wars.” Especially in the 1930s, the airminded took it upon their fraying nerves to anticipate, expect, and thereby potentially control, the approach of the bomb.

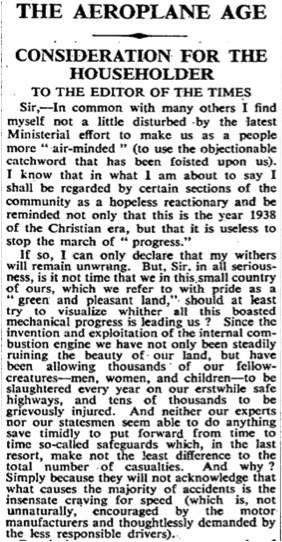

One prominent method through which civilians attempted to rein air power inside the zone of their comprehension was to train their ears to its sounds. No longer able to trust their eyes, the airminded listened to the modern acoustics that signaled flight and danger. Not uncommon was the complaint of the very noise of the airplane. This August 10, 1938, London Times letter exemplifies the concerns of a population who had already suffered an “apocalypse of the deregulation of perception” and were, once again, bracing again for another:

The blitzes that came a year later left cities caught in blackouts, where civilians learned to gain a heightened awareness of their acoustic environment. The routinized anticipation of air raids produced a population who were not only prepared, but who actively listened, for danger.

***

Aircraft exemplifies the history of technology as a double-edged sword — one that advances and modernizes a society, while also increasingly threatening its eradication. The trouble with the shock, the violence, the very newness, of machinery lies in how human sensibilities will integrate such instruments into their contemporary landscape of thought and experience. One might begin with words and stories: expressions to thread together a narrative that might otherwise appear hopelessly erratic and unpredictable.

To prepare for the future is to write about it: to talk about it, quite literally, to death. How many times has history repeated this philosophy of anticipating apocalypse by beating apocalypse to its own deployment? As early as a 1929 volume of the American publication Building Age, one writer announces, “This country is already airminded; it is now becoming airport-minded.” The piece turns to discuss transforming “an amazing variety of buildings” into flying fields and airports composed of passenger stations that closely resemble “a modern railroad terminal.”

The narrative here is to make the future something that resembles the past: a modern airport is like a modern railroad terminal. The July 31, 1935 London Times published part of a speech by one headmaster Dr. J. A. H. Johnston: “The road to progress lay in the air… it was obvious that within a very few years the private airplane would be as much a commonplace as the private motor-car and a wireless set was to-day, Britain was far behind the United States, Germany, and Italy in air-mindedness.”

The paradox of technology is more precisely the irony of war technology. Machines meant to drive progress not only threaten a suspension of progress, but the very termination of life itself. Before technology can be put to “productive use,” there often exists a period of experimentation where every incident of chaos desires only to relocate its origin of stasis and peace — in some place, time, or thing, of yesterday. Perhaps, then, technology begins too often as an experience for the sake of experience. As Frankforter intimates, after the initial take off, there is “The bare-faced lie to the effect that if you had a chance you’d do it again tomorrow.”

Jane Hu is our official correspondent for very recent history.