The Night Occupy Los Angeles Tore Itself In Two

by Natasha Vargas-Cooper

Around 8 p.m. on Wednesday night, the 300 people who have been occupying the lawn of Los Angeles City Hall for the past three weeks split themselves into two hostile camps.

Occupy LA’s decision-making body, the General Assembly, has been responsible for conducting the encampment’s business. As in most other cities, the participating members handle everything from ensuring the nightly meeting take place to doing financial research on Los Angeles-based bankers to cleaning up the trash. But on Wednesday, a large group of dissenters decided to occupy the General Assembly’s usual outdoor meeting space and assert themselves as the new regime. One man, standing at the center of the swirling and increasingly unruly crowd, yelled into a megaphone, “You don’t represent us anymore! We’re taking over! We’re the People’s Forum!” Rumblings of dissent and palpable animosity had been mounting in the camp throughout the afternoon. Informal meetings were held around the clock to hotly debate an issue that had factionalized the camp: weed.

There are two things that strike you when you come upon the Occupy LA encampment. The first is the sheer density of the tents: not a single thatch of grass pokes through; the lawn is bursting with tents and spray painted signs that carry slogans about everything from 99 percent to Wall Street criminals to 9/11 conspiracy theories. The place is packed. The second thing you’re likely to notice is the undeniable thick scent of weed smoke in the air. This is a curious aroma, given that the encampment is lodged between the California state courthouse, the offices of the City Council and LAPD headquarters.

Occupy LA is also three blocks away from Skid Row, the city’s biggest open air drug market and homeless encampment. Some people claim that the drug use in the Occupy camp is a spill-over effect. Those who buy drugs on Skid Row, especially the homeless, can smoke in a safe, free space among the Occupy tents, instead of buying an hourly room in one the crime-riddled slum hotels along 4th Street. Other people in camp claim the drug problem is homegrown.

Drug use has been a key conservative talking point used to undermine the various Occupy camps around the country. In Occupy Los Angeles, though, smoking weed has become a wedge issue dividing the camp into increasingly entrenched groups.

As one original organizer of Occupy LA described it, “on one side there’s the hardcore Politicos-Get-Shit-Done process freaks and on the other are people who think they are starting a new society.”

Smoking weed cuts to one of the main dilemmas within a leaderless, horizontal, movement like Occupy Los Angeles: who makes the rules? Who enforces the rules? Going even further: should there even be rules? Is this a narrowly focused social movement bent on economic reform through massive but nonviolent participation? Is it a petri dish of something new?¹ There is a wing of the Occupy LA that sees their encampment as a radical new mode of living; one that not only rejects income inequality, but any sort of action that enables one group to represses any other. This means contempt for anything like a parliamentary up or down vote, or adopting the same drug laws as ‘the outside.’ When someone lights up, especially during daylight hours, there is an instant sense of polarization between those who are willing to behave and those who aren’t. Finally those differences exploded.

* * *

Earlier in the day, Kat, a twenty-something blonde with a big beautiful Slavic face and dirt underneath her fingernails, convened an affinity group at the north side of City Hall to discuss adopting Occupy New York’s code of conduct: no drugs, no violence, no abuse. If the affinity group could come to a consensus, then members of the group would make a formal proposal to the General Assembly recommending that the camp adopt the ground rules. About sixty people were in attendance for the afternoon meeting. Most were young, many were Chicano, there were some purposefully well-dressed young white guys in collared shirts and ironed pants who were not camping but regularly attending meetings. There were a few older people in the group with the vibe of being life-long professional activists. About six men donned the traditional anarchist garb: pulled-up hoodie, black bandana around their face, an implacable look in their eyes.

“I don’t understand why people who want to smoke weed can’t just go across the street to do it?” one young man in camouflage shorts and black sweatshirt said. About half the group raised their hands up and twinkled their fingers in agreement.

Another young man stood up, clearly agitated, and began pacing around the inside of the circle: “Is it alright if I stand in the middle of the circle? I don’t want to be too domineering or anything. Ok, right, it’s like, if you create a code of conduct, it’s like you’re creating a separatist doctrine. You’re creating an Us and a Them. Why do you guys want to act like cops? It’s the cops’ job to divide us! We left society to avoid them. Why do you want to bring that shit here?” Kat thanked him for speaking and moved on to the next person who had signed up to talk.

Speaking slowly with a tense edge to his voice, a man in dark sunglasses asked the crowd, “What the fuck is wrong with us? Why are we talking about this instead of figuring out how we’re going to hold a vigil for the Oakland protesters who were gassed last night?” This time people started to clap. Things got increasingly more heated and more abstract — “Are you going to call coffee a drug?” — as each speaker entered the circle. Those who were in favor of the code of conduct were accused of wanting to purge outsiders and create a two-caste structure within the camp. Those who opposed the code were, indirectly, called selfish and short-sighted.

Ideological disputes on the nature of law, order, and a group’s ability to self-police continued for the next two hours. At a few different moments it seemed as though the group would be swayed to recommend the code of conduct but inevitably someone (usually with a black bandana around their face) would demand to know how the camp would enforce the rules. “Who’s going to take responsibility for kicking people out of the camp?” When no answer was given, the debate would kick up again, and spiral, and go off the rails.

Eventually, there was so much interruption, and rancor, Kat found herself overwhelmed and snapped at a woman who had continually tried to speak out of turn. Breaking away to have a cigarette, Kat told me that she absolutely believed a code of conduct should be passed but was certain that the issue would not even reach the General Assembly for some time. “We’re having too many growing pains right now,” Kat said, and exhaled smoke and tossed her hair to the side. “But I’m sure we’ll figure something out,” she said, with a polite smile. By the time Kat finished smoking, the group had collapsed with no clear resolution for the General Assembly that was set to take place in an hour.

* * *

The General Assembly is made up of self-selected committees charged with dealing with nearly every facet of camp life. There is a committee for food, research, demands, media, facilitation, sanitation, “zero waste “and arts. Every General Assembly meeting begins with a ten-minute update and then about two hours of reports from various committees. At the end there is an open discussion. On Wednesday, the General Assembly had invited members of the Los Angeles City Council to join the meeting, in an effort to display that the City’s concerns about sanitation and waste were being addressed. A few council staffers were spotted at the designated time for the meeting. They did not stay long.

Because even by the time the General Assembly was ready to meet at 7:30 p.m., things were unraveling. A large group, made up almost entirely of men, stood in a circle denouncing the General Assembly and their efforts to “police” the camp, particularly regarding drinking or smoking weed. Anyone who spoke in favor of a code of conduct was aggressively booed. Adding to the morass were four different men looping in and out of the circle, each armed with his own megaphone, shouting their own grievances and rhetoric. When a runner from the General Assembly made the announcement that they would begin the meeting, he was thunderously shouted down, then someone yelled out “The GA is dead!” and the crowd erupted in both celebration and shock: “We don’t want you or your fucking procedure!” One male protester, in an army helmet and no shirt, cried out as shoving matches erupted between several groups of men. The young man who was leading the informal group yelled: “This is the People’s Forum! There are no committees, there are no rules, everyone gets to speak. Get in a circle! GET IN A CIRCLE!” A majority of the crowd abided, although they were openly chastised when the circle took on non-circle shapes.

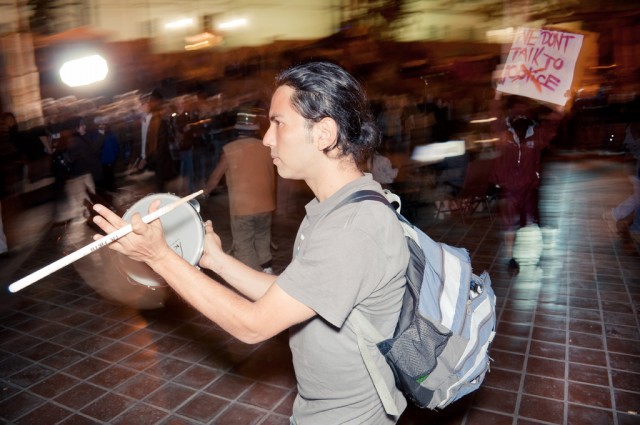

A facilitator from the General Assembly tried one last time to get the group’s attention through a call-and-response tactic. He was shouted down by two men, one of whom was shouting directly in his ear. Then it was announced that there would be two minutes of drumming. The loud thumping gave way to spastic dancing and eventually some primal bellowing.

The People’s Forum held to their pledge to not have time limits or committees. Some people spoke for twenty minutes at a time. In the three hours that they commandeered the steps of City Hall, the People’s Forum denounced enforcing any code of conduct, cheered “ending the disease of perfectionism,” spoke about inequality in the camp and outside, and, for the most part, thoroughly trashed the General Assembly.

Less than a dozen of the General Assembly members were left standing in their original meeting area. Eventually, they gathered a small group to meet on the other side of City Hall. About thirty more joined the small group within the hour.

They sat cross-legged on the cold cement, and debated whether they should spend the evening attending to usual business or reviewing how they had just been overthrown. They spent the next two hours discussing the People’s Forum.

In the end, no code of conduct has yet been adopted by either the General Assembly or the People’s Forum.

¹ There is also a third scenario, one that I feel is most likely. Occupy LA is a large collection of fringe folks, similar to a typical contingent found at any large protest. Yet for reasons greater than the Occupy Movement can control, they have not been able to attract the participation of more mainstream elements at, least not in Los Angeles. There is, for example, no regular presence of labor unions, left-leaning non profits, or any of other hierarchical group. That may be by design: if these groups, which are well-organized and have a centralized leadership, were to show up they would most likely be greeted with suspicion and hostility. There is a distinct and protective feeling within Occupy LA of “This is My First Movement.” Yet it’s no wonder there are protesters at City Hall, even if they are fringe. The real question is, where the hell is everybody else?

Related: How I Got Off My Computer And Onto The Street At Occupy Oakland

Why Should We Demonstrate? A Conversation

Occupy Boston: The Glory And Imperfection Of Democracy

What Does The Bonus Army Tell Us About Occupy Wall Street?

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Lessons For Occupy D.C.

Why the Tea Party Hates Occupy Wall Street

Natasha Vargas-Cooper is a Los Angeles-based reporter. Photographs are by Eric Spiegelman, a web producer in Los Angeles.