What Does The Bonus Army Tell Us About Occupy Wall Street?

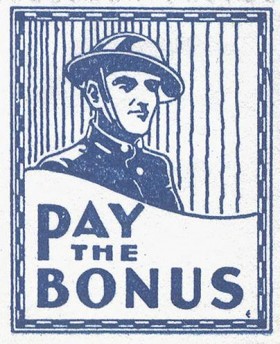

They called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force, or the Bonus Army or Bonus Marchers for short, and in 1932 they set-up semi-permanent encampments in Washington D.C. Nearly 80 years later, people are occupying Wall Street, and many, many other places around the country. And as loud as the shouts of deliberate mass media ignorance were a month ago, the Occupy movement is not all over everything, and it’s as difficult to avoid coverage now as it was to find it then. It seems to be a unique construct, a product of now — nonviolent, persistent and inchoate in the sense of there’s too much to say (rather than not being able to say it). But they’re walking in someone else’s footprints, whether they know it or not.

Comparisons of Occupy Wall Street to the Bonus Army are not entirely new; mentions have been made in the past month (and more recently by Frank Rich in his piece looking at the new Class War), and rightfully so. In fact, efforts to parse Occupy Wall Street by historical comparison are a new cottage industry. Correlations with the Tea Party (both of them) are popular, based purely on the putative populist nature of each, and echoes of the war protests of the ’60s do pop up as well.

No one is suggesting that a wormhole opened up and pulled a historical event straight into modern times, or that, say, a magic shoe was found and worn by an Occupy Wall Street organizer, filling him or her with the channeled knowledge of Eugene Debs manifesting itself in the form of a well-managed listserv. I just recommend that a comparison the Bonus Army is apt, because in 1932, what they did basically was Occupy D.C.

The arrival of the Bonus Army was quite dramatic. They came from all over the country. Some of them just picked up stakes and brought the family with them, figuring there was nothing left to come back to. They made their way, some in groups, some one by one. More fortunate America helped them along: road and bridge tolls were waived, and the travelers weren’t rousted like the everyday forgotten man. When they reached D.C., they set up camps, tents when they could, or shanties cobbled together from tarpaper and scrap wood and whatever they could scrounge.

This is the account given by Evelyn Walsh McLean, wife of the owner of the Washington Post (and owner of the Hope Diamond):

On a day in June, 1932, I saw a dusty automobile truck roll slowly past my house. I saw the unshaven, tired faces of the men who were riding in it standing up. A few were seated at the rear with their legs dangling over the lowered tailboard. On the side of the truck was an expanse of white cloth on which, crudely lettered in black, was a legend, BONUS ARMY.

It’s not exactly the same sense that you get from a Flickr feed of Occupy Wall Street, but it does resonate with the sense of purpose (once you get past the rote Dirty Hippie response) of those willing to spend a month or more on what’s essentially a Manhattan sidewalk.

But considering the variety of opinions considering what might have resembled or inspired the current movement, let’s ask the question: are these historical parallels are useful at all? Is there utility in this, or is it just a chaff thought experiment, noise to the signal?

For perspective on that, I had an email conversation with historian William Hogeland, author of (most recently) Declaration: The Nine Tumultuous Weeks When America Became Independent, May 1-July 4, 1776. At his website, he’s been writing about the history of American economic protest and how it ties in with current circumstance. (His suggested reading list is of particular value.) Also note that Hogeland’s bailiwick is not the Bonus Army or the Great Depression, but rather the populist movements of the 18th century, when the United States was a concept and not yet a practice.

I asked him straight up if it’s fair to talk about Occupy Wall Street in the context of its antecedents. He (naturally) finds them entirely valid. “People generally don’t seem to know much about the long — very long — tradition of American protest specifically over economic issues and high finance’s corrupting relationship to government,” he said. “The tradition is right under our noses, but until Occupy Wall Street, we’ve often thought of protests as occurring over specific, anomalous wrongs that need to be corrected, or over broad ideology, but not over the way money, finance, investment, and taxation pervasively work in our society.”

This is one way that the Bonus Army of 1932 is entirely unlike Occupy Wall Street: the Bonus Army had a very specific redress they were seeking. They were veterans of World War I. After they returned to the US, an act was passed in 1924 that gave the vets a bonus in the form of a fee per day of service, but it stipulated that the bonus would be held and bear interest for 20 years. By 1932, when the Bonus Army converged on D.C., some of the participating veterans (of a truly horrific war, btw) had been out of work for years. What they wanted was a bill to be passed by Congress and signed by President Hoover that would permit the vets to access this bonus before the 20-year maturation date. And by early summer of 1932, there were roughly 40,000 of them in D.C., waiting.

Occupy Wall Street is somewhat more diffuse in its goals, and more in line with the 18th century events that Hogeland writes about. Though, to be fair, Occupy Wall Street has been very, very vague (and purposefully so) as to what they’re looking for. I asked Hogeland if that was in any way unique, from an historical perspective: “The absence of articulated demands on the part of OWS may be unique or at least highly unusual in American economic-related protest. The 19th-century Populists demanded specific, radical legislation to benefit ordinary people. The Whiskey Rebels wanted fair taxation. The Shaysites wanted fair taxation and debt relief. And they said so.”

Maybe it’s spurious to compare the circumstances of the two: then, the occupiers were veterans, crushed by the circumstances of the Great Depression, moved to uproot their lives in hopes of a very real result, and now, a melange of the generally dispossessed, moved by frustration over a financial system suspected to be rigged. There are similarities, so maybe not as spurious as it is too tenuous to avoid refutation.

The two movements shared an analogous backdrop. Just as Occupy Wall Street unfolds in the shadow of the fiscal crisis of 2008 and the Great Recession that followed, the Bonus Army congregated in the full bloom of the Great Depression. Without the downturn, neither protest actually could have happened. There was even a specific federal program that inflamed each: instead of the TARP program that doled out free taxpayer money to financial institutions recently, Hoover had established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, an entity to save the large banks and railroads through government loans, just months before the Bonus Army declared their march. So both the Bonus Army and Occupy Wall Street were set into motion in response to almost deliberately provocative federal policy, and the economic horror show that necessitated it.

And as Occupy Wall Street has current celebrities, the Susan Sarandons and Alec Baldwins, the Kanye Wests and the Jeff Mangums, stopping by, the Bonus Army had one of the more popular military figures of the time, Gen. (Ret.) Smedley Butler, then the most decorated Marine ever, visit and give a pep speech:

Men, I ran for the Senate in Pennsylvania on a bonus ticket. I got the hell beaten out of me. But I haven’t changed my mind a damned bit. I’m here because I’ve been a soldier for thirty-five years and I can’t resist the temptation to be among soldiers. Hang together and stick it out till the gates of Hell freeze over; if you don’t, you’re no damn good. Remember, by God, you didn’t win the war for a select class of a few financiers and high binders. Don’t break any laws and allow people to say bad things about you. If you slip over into lawlessness of any kind you will lose the sympathy of 120 million people in this nation.

Try to imagine that speech given in small bites, repeated in waves throughout an Occupy Wall Street general assembly, and it wouldn’t be out of place at all, would it? (And some not-bad advice to boot.)

And there is one trait that, of the major American protests, is shared only by Occupy Wall Street and the Bonus Army, that of a population, moved by varying degrees of perceived unfairness, to make not just a statement but to erect a semi-permanent edifice, to occupy. Not a march, not a riot, not a long-term picketing effort, but people uprooting themselves and planting themselves in a temporary autonomous zone, in the interest of making a point. Occupy Wall Street has Zuccotti Park, and the Bonus Army set themselves up primarily Anacostia Flats, across the river to the southeast from the Capitol in a bit of land within the skewed cube of the D.C. city limits that would otherwise be Maryland.

To be fair, while they both share occupation as a tactic, Occupy Wall Street is using it to address the ineffability of its goal in a way that did not confront the Bonus Army — not just a squishiniess in targeting, but the conundrum of possible tangible results. Says Hogeland, “Sitting at a white’s-only lunch counter deliberately breaks the precise law you want ended, and it calls the world’s attention to the law’s immorality; arrests dramatically underscore all that. Civil disobedience doesn’t work when there’s no law for protesters to deliberately break in hopes of getting it ended.” Setting up a camp, attracting attention, is a different creature than civil disobedience, and is more like the polite but insistent refusal to not be paid attention to. The Bonus Army was ready to leave once they got their bonuses. It’s as if once Occupy Wall Street stops occupying Wall Street, they will lose cohesion and purpose, as Occupy Wall Street will be ready to leave when, well… I guess we don’t know when they’ll be ready to leave, or what the outcome will be (barring further drum circle controversies). That will be one for waiting.

The historical context of American economic protest is not one easily digested in the course of a brief article on the web. This is Hogeland’s thought on the subject (and why you should consult his work):

We don’t know much about that founding protest tradition of the 1700s, but the famous founders did! They bent all their efforts to squelching it. That’s not a very nice thought, and it raises uncomfortable questions. Everybody from the Tea Party to the liberal/conservative establishment to Occupy all Street wants to claim the spirit of the American Revolution in the form of one or more of the famous founders, but only the modern Wall Street Hamiltonians are on any kind of solid ground with such claims — and they never want to admit (or even know) what Hamilton was doing. So maybe that’s why we don’t want to know too much about the original American protests and riots over economic and finance matters — protests that had a lot to do with getting us here at all. Those protests raise more questions than they answer. And neither establishments nor movements like questions.

This is not a new game being played. Occupy Wall Street is the latest iteration, and what is being “protested” is not something the Department of the Treasury did three years ago, or even something the financial services industry has done in the atmosphere of deregulation initiated by the Reagan administration. This is just continued seismic activity caused by the intrinsically American tectonics of capital. Maybe the game is rigged and the outcome of Occupy Wall Street will be less good than we hope. But let’s look at the Bonus Army, as we know how that went down.

The bill that would have immediately released the bonds to the Bonus Army? It had support, but was ultimately defeated by House Republicans, worried about balancing the budget. The Bonus Army stayed, resisting numerous incentives to decamp. So, on July 28 skirmishes with the local police led to an attack on the Bonus Army by the actual Army. Gen. Douglas MacArthur led a force consisting of infantry (bayonets down), cavalry and six tanks, which razed the shantytowns of the Bonus Army, pushing them into the river as if the Bonus Marchers were the Kaiser’s men fifteen years previous. The camps were torched. Two Marchers were shot and killed. And that was the end of it.

But actually it wasn’t, as the effect of the Bonus Army, the fallout, was a little bit less than immediate. For one, it contributed to the defeat of Herbert Hoover, as the rout of the Bonus Army was terribly received by the American public, and 1932 happened to be an election year. And while obviously other factors contributed to the end of the Hoover administration, the administration that followed was the Roosevelt administration, which effected an unprecedented amount of social reengineering in the form of the New Deal.

In fact, the former Bonus Army benefited greatly from the New Deal, as the opportunities afforded by the various initiatives (the TVA, the WPA and the CCC) employed the scattered forces of the Bonus Army, and employment ended up being more life changing than the early redemption of a service bonus.

So let’s cling to that optimism. It would be awesome if at the end of the Occupation of Wall Street the system was righted, income inequality dispersed, banks not big enough to fail, etc. Not likely, but it would be yell-out-loud awesome. But if the ripples of Occupy Wall Street are only gradual and only turn into actual waves when they crash on shore in a year, or two, or five? It would be a worthy accomplishment.

Brent Cox is all over the Internet.

Images via Wikipedia.