The Fumes Of The Wine Do Ascend, And Other Pieces Of 17th-Century Drinking Wisdom

The Fumes Of The Wine Do Ascend, And Other Pieces Of 17th-Century Drinking Wisdom

by Lili Loofbourow

If you’ve never considered drunkenness a sign of loyalty, or sobriety as treason, it’s unlikely you will ever understand the English. In England, toasts, the time-honored tradition of watching hapless well-wishers fail at stand-up comedy, were once serious affairs. So intense were the feelings inspired by what one drank and why that during a brief but sober period, toasts were legally banned.

In this edition of John Dunton’s “Athenian Mercury,” which, as the first advice column in English, was once the go-to source for wisdom for many a muddled 17th-century Londoner, the city’s citizenry writes in with booze-related questions. Why red eyes? Double vision? How does God feel about it all? Why can you scare a drunk man straight? And why, above all, does drinking unfit you for the, ahem, “combats of Venus”?

For certain elements of early modern England, drinking was subversive. Marika Keblusek (whose article “Wine for Comfort” provides a fascinating overview of exiled literary boozehounds around the time of the English Civil War) describes drinking as “an integral part of friendship, conviviality and mirth.” Drinking to a friend’s health represented a real effort, especially among exiled Royalists, to symbolically unify a once-vibrant drinking group that had since parted ways. Drinking someone’s health could constitute an act of Royalist resistance against the Parliamentarians, who had won the Civil War (and yes, banned toasts).

In 17th-century London, knowing what someone drank and with whom could offer a rough indication of their politics. For the first half of the century, wine-drinking correlated to Royalists and Cavaliers, whose wine-flushed cheeks were “as starred as the skies.” Beer-drinking and teetotalling were more typical of Parliamentarians (also called, delightfully, Roundheads).

By the end of the century, the line between beer-drinkers and wine-drinkers had blurred, but this did not signal peace. New faultlines emerged, this time among the wine-drinking contingent. Thanks to deteriorating trade relations between England and France, the feeling was that importing French wines, no matter how delicious, meant pouring English gold into French coffers. As a counter-measure, the English — especially the Whigs — made policies designed to increase Portuguese imports. That, in case you wondered, is how port got its name and became the ubiquitous English table wine.

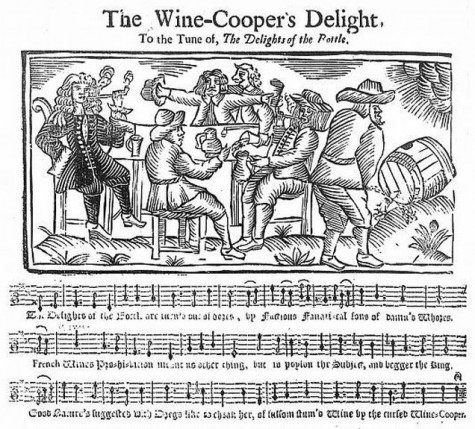

Tories were none too happy with that development. One broadside (pictured here), called “The Wine-Cooper’s Delight,” warned of a horrible Wine-Cooper who gives his clients undrinkable poisonous swill, and blames the lack of good (French) wine on the Whig “factious fanatical Sons of damn’d whores” (to quote the first line of the lyric).

In sum, by the time the Athenian Mercury went into print, claret was associated with Tories, port coded as Whig and England as a whole was still reeling from the debauchery that followed the Protestant (and Puritan) Interregnum. Propelled by years of Puritan repression, the Restoration took partying to a whole new level.

Certain factions became associated with too much drinking (Royalists, Tories) while others were lampooned for not drinking enough (Parliamentarians, Whigs). Yes — according to the Tories,not drinking can be one of the worst vices.

Thankfully, Angela McShane Jones¹ is there to explain the Tory mindset:

By the late 1670s and 1680s, the political divide between ale and wine gave way to a politicisation of drunkenness. Whigs and Tories now attacked each other in terms of their consumption of drink, using established ballad-drinking discourses. … Tories made a virtue of their revelling. They claimed a major difference between their merry, loyal carousing and the miserable, seditious sobriety or hypocritical sousing of the Whigs. Thus, the Whigs were doubly damned either as miserable misers who would not buy or enjoy a drink, or as the worst kind of drinkers, who did not drink to be merry or in good company but to be drunk and cause trouble.

Drunken Whigs, in other words, were billed as the Ted Haggards of their time. Even the Whig commitment to (partial) sobriety worked against them. Here’s how the Tories managed that, in one of the most impressively self-sabotaging feats of political spin you’re likely to encounter: When Whigs called Tories Catholic (worst possible insult, by the way — for a 17th-century Godwin’s law, swap “Papist” for “Nazi”), the Tories retorted that at least they preferred wine to women.

The Tory message, spelled out, is this: we drink too much to get it up, therefore the whoremongers who are destroying society with their working penises are obviously Whigs.

“Sober Whigs,” Jones explains, “threatened respectable wives and daughters with their ‘presbyterian itch’, and were a danger to good society and to innocent women. Again, the evidence was against them, for any man not in the alehouse or tavern drinking himself incapable, as any loyal subject would be, must be available for whoring — and must, therefore, be a Whig.”

That’s right: subjects proved their loyalty by drinking themselves into impotence, and “the refusal to drink a loyal health marked out the seditious and could lead to threats of violence in ballads and in real life.”

It’s possible to trace a parallel literary history of drunkenness. Falstaff might be the most famous and most beloved drunkard the canon. The Cavaliers take up where he left off. Swearing off booze in “His Farewell to Sack,” Robert Herrick bemoans that his brain has grown “uncapable of such a sovereign,” which with its “mystic fan” works “more than wisdom, art, or nature can, to rouse the sacred madness” and “awake the frost-bound-blood.” Then came the libertines, who ensured, among other things, that Douglas Adams would have a historical model for Zaphod Beeblebrox.

Having spent some time on the pro-drinking set, it’s worth noting that plenty of anti-drinking literature exists too, much of it sermons. (I’ll spare you.) There were broadsides too — many of the images used here come from the “Drinking” section of Samuel Pepys’ broadside collection, more of which can be found here. Of the more serious critics, William Hogarth’s Beer Street and Gin Lane prints are the most striking (though done much later, in the 1750s, the street scenes are well worth a look). Among writers, Richard Younge is the most satisfyingly vituperative: “As the basilisk is chief of serpents, so of sinners, the drunkard is chief. That drunkenness is of sins the Queen: as the Gout is of diseases, even the root of all evil, the rot of all good.”

He goes on, relishing his own disgust and giving us a sense of what 17th-century alcoholism might have looked like:

Nor need it seem incredible, that common drunkards should drink thus, for they can disgorge themselves at pleasure, by only putting their finger to their throat, and they will vomit, as if they were so many live whales spewing up the ocean; which done, they can drink afresh.

And now, without further ado, here are the questions that, like so many live whales, Londoners spewed up at the feet of Dunton’s Dear Athenian. Beware. As Younge so eloquently put it: “the Drunkard is like some putrid grave: the deeper you dig, the fuller you shall find him both of stench and horror.”

Why do the buzzed act sillier than the completely knackered?

Q.: Wherefore are those that are tippled only, or a little drunk, more foolish and toyish than those that are very drunk?²

A. Because they have only the judgment lightly stirred and troubled, but the others have the senses totally depraved, and can neither judge ill or well.

Moral: Frothy judgment is worse than none at all.

My old college drinking buddies are killing me!

Q: My education was chiefly at Cambridge, where I continued five years, in all which time I was not so industrious to ply my studies as to keep company, especially at drinking bouts. Since my leaving the University (which has been two years) I have continued under the same method, which I am sensible has brought me upon the confines of a fever, as by several light symptoms I have reason to fear, particularly a vast quantity of white scurf upon my tongue, which is supposed to proceed from the immoderate heat of the blood. However, I find no inward signs of it. My age is 24, my constitution indifferently hearty (especially when I neglect drinking) I am by nature very choleric and passionate, I sleep little, but when I do, I am extremely troubled with horrid dreams, which puts me upon vows of repentance, but they soon vanish when the day and my old acquaintance appears.

Yet I am (without vanity) naturally of a good disposition and very inclinable to piety; I desire to know your opinion in this case, whether you think upon my forsaking drinking, I may avoid the fever that visibly threatens me? If not, how long you imagine it will be ere it comes, and how I ought to behave my self in the interim? And lastly, what may be the cause of these terrible dreams, and what effects ought they to have upon me?

A: The best Receipt against impiety, an impending fever, and terrible dreams, is to throw off all your old companions, and lead such a life as may not be a scandal to your cloth; if you do not, all these warnings, together with your education will appear in judgment against you. Read the Life of Mr. Fulks and you will exactly read your own, and we hope a due reflection may secure you from a parallel exit.

Moral: Ditch ’em. On Judgment Day, a college education will count against you.

Why does fear kill a buzz?

Q.: How does a fright bring a drunken Man to his wits?

A: The spirits of the liquor mounting into the brain, intoxicate the animal spirits, which are chiefly lodged there, and occasion drunkenness, but when the heart is oppressed by a fright, the animal spirits fly to its assistance, and in their passage through the blood, are purified and cleared from the intoxication, as the salt-water by running through the channels of the earth loses its salsitude and becomes fresh.

Moral: The animal spirits that live in your brain get drunk. When you’re scared, they rush to the heart. En route, they get purified by your blood. It’s science!

I got married drunk! Doesn’t count, right?

Q. Whether a person made drunk (so that he is capable to return pertinent answers to the Minister, either his own, or as dictated to him) can at such a time be properly be said to be married according to the Law of God?

A: [Ed. note: parts of the Mercury’s response are illegible, as indicated by *] Before I return a negative answer where a * Oath has already been passed, as the letters by * affirm, I shall premise that other different * Oaths were taken, as that the Man was made drunk; for proof of which, they alleged that, being asked, “Wilt thou take this woman to thy wedded wife,” he made no other answer but this, “I must go to piss.”

But upon a supposition that by several times asking, he made use of all his own responses, it won’t follow that the Law of God * look upon this as a marriage, for the wisdom of the Church appointed the Matrimonial Office to be used * that the words in it are to be offered by such persons as know what they say. The words * are not the essential Act of Marriage, but a public Sign or Solemnization of a legal contract made between the parties beforehand. Now, words being only the index of our minds, and when words are forced upon us by undue means, the sense of which we neither understand nor will, ’tis a sacrilegious rape committed upon the soul, which by how much it is of a more excellent nature than the body, by so much greater is the injustice, and deserves a severer inquisition than what our law requires for the satisfaction of bodily rapes, and all persons concerned in such actions are a sort of Spiritual Pimps.

Moral: Hard to say. Not exactly, because the words should be the public expression of private intent, and your friend’s intentions were clearly more micturient than marital. The trouble is, if it does count, it’s soul rape, which is worse than regular rape, and whoever intoxicated him is a soul pimp. This is why friends don’t let friends marry drunk.

Why are drunks so reckless?

Q.: Why a Man when he is in Drink is less apprehensive of any bodily damage (as falling down a Precipice, receiving a wound, or the like) than a Sober Man?

A.: This is partly in the answer about muscular motion and mad-men, who from the violent and over-brisk motion of the spiritous particles in the Nerves, are made to surmount pain and insensible almost of the Weather and Objects, are rendered thereby vertiginous and false.

Moral: The nerve-particles go nuts, and you stop feeling pain and weather.

Why do drunks cry?

Q.: Wherefore do Drunkards weep easily?

A.: Because, they have their Head full of Fumes and Vapours, which contracted together, do discharge themselves by Running out at the Eyes, on the least occasion, or trouble, Veritable, or Imaginary.

Moral: Wine starts a weather system in your head and makes you leaky.

Why did God make Visine?

Q.: Why have Drunkards, ordinarily, their Eyelids very Red?

A.: Because the fumes of the Wine, do ascend from the Stomach to the Head, partaking of the Natural Heat of the Urine, do affect the Eyes and Eye-lids also; By some boyling Humour and Fluxtion; The Eyes being parts, very delicate and more easie to be affected.

Person A drinks wine and water. Person B drinks wine. Why does A get more sick?

Q.: Wherefore is it, that those that are drunk with Wine mixed with Water, have more Crudities of Stomach, and find themselves more Loaden, then those who drank pure Wine only?

A.: Because pure Wine is more Hot, and Contributes more to its own perfect digestion, then when it is mixed with water.

Moral: Pure wine is a magical substance that helps you digest it the more of it you drink. The solution to this problem is at the bottom of a bottle.

Why do drunksss slurrrrr?

Q.: Why do those who are drunk, stammer and stutter in speaking?

A.: Because, that the tongue being by nature spongious, is easily imbued with too much humidity by the excess of drinking and becomes heavy and as it were flat, insomuch that it cannot distinctly pronounce and express the conceptions of the mind, with a voice neatly articulate. Besides that, the trouble of the mind, made so by the wine, is a co-operating cause.

Moral: Spongy tongues absorb too much fluid and get heavy.

Why aren’t alcoholics the picture of health?

Q.: Why are the great and famous drinkers less robust and strong than sober persons?

A.: Because by moistening and wetting themselves so much, they become more soft and effeminate; besides, the heat of the wine, which is not natural, doth stifle in them, or at least enfeeble the natural heat.

Moral: Wine makes you girly and kills your “natural heat”.

Why am I seeing two of you?

Q.: Wherefore do drunkards seem sometimes to see doubly the same object?

A.: ’Tis because that humidity doth diversely affect the muscles of the eyes, in so much that one is more closed than the other. Or else, according to the Philosopher, the reason of this is, that it seems to those who are drunk, that all things turn round because their brain is troubled; by reason of which, for one only object, they think they see two, or more. For ’tis certain, that a body turned round with quickness, doth not seem one, but many, because it returns suddenly, and represents itself often to our sight.

Moral: Humidity is bad for eye-muscles. Or, if you want to listen to Aristotle, your brain is confused and thinks one thing is lots of things.

How can drinking make you thirsty?

Q.: Why is it that those who have drank a great quantity of wine are afterwards very thirsty?

A.: Because wine taken immoderately over-heats the body, by which adventious and strange heat, it makes it to desire moist and cold things, and such is drink.

Moral: Wine is hot and dries you out.

Please explain ‘whiskey dick’ to me!

Q.: Wherefore are such who are too much charged with wine and meat indisposed to Venus Combats?

A.: ’Tis because their digestion and concoction is tardily and not easily made, by which means they are furnished with little seed. And that which was in the body before is not so apt to move, because the body is bound and constipated by the too much repletion of meat and drink and the natural heat so much employed in the concoction thereof.

Moral: The sperm you already have is sluggish because all your heat is going to digesting wine and food. Same reason you’re not making new sperm, either).

Why do construction workers get drunk faster than couch potatoes?

Q.: Wherefore are laborers sooner drunk than those that live a sedentary and lazy life?

A.: Because laborers are ordinarily dry and thirsty, labor and exercise drying up their humors, but those that are sedentary and lazy, their body being more humid, do thirst less, and although they should make some excess in drinking, their bodies would not so easily be soaked and imbued, as if it were dry, so that they discharge more by urine, and are less drunk.

Moral: Working men are dry. The bodies of lazy people who sit on their duffs all day are moist, so they absorb less alcohol. Instead, they pee it out.

¹ Note: much of the foregoing history and analysis comes from the following collection of essays, edited by Adam Smyth: “A Pleasing sinne: drink and conviviality in seventeenth-century England.”

² Spelling and punctuation for all entries has been modernized.

Lili Loofbourow is a writer living in Oakland. She blogs as Millicent over here.

Read previous installments of “Dear Athenian Mercury” here, here and and here.

Images provided courtesy of the English Broadside Ballad Archive