Dear Athenian Mercury: The Non-Reproductive Sex Issue

by Lili Loofbourow

History steers clear of the masturbators. It sidesteps erectile dysfunction and abortions in favor of tidy genealogies whose bustling branches confirm the basically Darwinian principle that, when it comes to sexual habits, those who propagate leave better paper trails. The exceptions aren’t exactly razed from the Book of Life, but their contributions are usually buried in cavernous parentheticals and shady marginalia. They don’t pop up much in the main text.

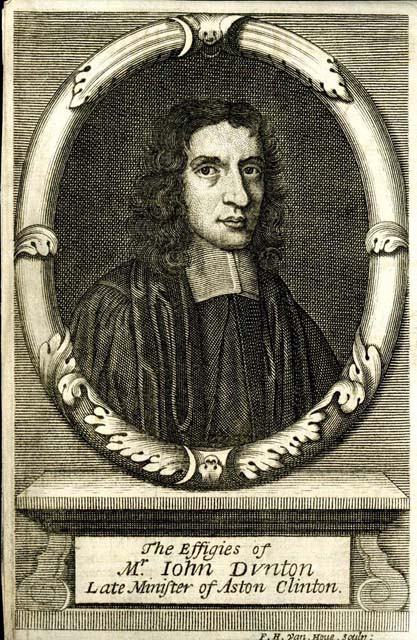

Luckily for us, there’s the Athenian Mercury, the wildly popular advice column to which many a nameless 17th-century Londoner turned with his or her burning questions. If the Mercury avoided mentioning the unmentionable, it made up for it by documenting much of the undocumentable. Students of advice-column history (and blog history) would do well to honor one of the founding fathers of the form, John Dunton, and marvel at how he both educated a curious nation and managed to make a pretty sensational publication not just profitable but also semi-respectable.

Dunton¹ — whose father deemed him too stupid for the clergy and apprenticed him to a bookseller instead — wanted more than money; he wanted to be a legitimate moral authority. Or at least to be considered one. If he couldn’t be a rector, he would build his own platform from which to instruct people on good living.

The trouble was that nobody needing advice was very likely to go to a bookseller in The Poultry (the district where Dunton’s shop was located) and an advice column with no querists just doesn’t work. Dunton needed publicity and status, so he founded the Athenian Society, a fancy-sounding organization with a fictional panel of experts that included a “Civilian, a Doctor in Physick, and a Chirurgeon.” He later “expanded” the Society and publicized its secret membership with help from Charles Gildon, whose History of the Athenian Society (written when it was only five years old) claimed it had twelve illustrious-but-secret members including a divine, a physician, a poet, a philosopher, a mathematician, a lawyer, an Italian, a Dutchman, a Spaniard and a Frenchman. Of those “experts,” exactly three were real.

Nor do the layers of deception end there: Dunton went to the trouble of printing the first few issues of the Mercury under the pseudonym P. Smart. Eventually he decided he wanted credit, so he “came out” as the real printer. In later years, Dunton would pretty much admit his own fakery and (in a move lesser imitators would copy) reframe it as brilliance: “As the Athenian Society had their first Meeting in my brain, so it has been kept ever since religiously secret.”

Plenty of savvy Londoners figured out that the Society was fake. There were knockoffs, parodies, even a play. Some nicknamed Dunton “the maggot,” partly because of his ethics, partly after one of his early publications, a collection of poems by Samuel Wesley called Maggots, or Poems on Several Subjects. (Wesley, by the way, was Dunton’s brother-in-law, one of the few real members of the Society, and John Wesley’s dad.) For his part, Dunton not only embraced maggot-hood, he tried to redeem it as a social category. Some years later, writing in secret as he hid from his creditors (things didn’t end well), he wrote this in his memoir:

“… yet if, after all I can say, my Ideal Life must pass for a maggot, I must own it my own pure maggot; the natural issue of my brain-pan, bred and born there, and only there…”

It’s touching that London’s maggot made space not just for the philosophers whose approval he craved, but for the less accepted types of human sexuality, too. The lesbian, the knocked-up (but super-pretty) lady, the guilty masturbator, and the guy who really just doesn’t like kissing — they could all turn to the Athenian Society for guidance. Not many moral codes are capacious enough to do the work of a Dear Abby, a Judge Judy and a Dan Savage. But Dunton’s was.

Here’s what the Mercury’s own pure maggot had to say about the sex that bred in the brains (but not the beds) of London’s querists, brought to you from the brainpan of history.

Why bother kissing?

Q: Is not kissing an insipid thing? Is there any real pleasure in it?²

A: We must leave that to your own experience, though ’tis much as the person is.

Moral: You’re a bad kisser and a drip.

Why can’t we kiss all the time? It’s just like shaking hands!

Q: Why may not a woman, without any impeachment to her modesty, suffer a man to kiss her often, as well as to shake hands with her?

A: Are kisses insipid still? But to let that unlucky question alone, though only to come to another: If the innocence of applying lips to lips be argued from that of applying hands to hands. Ladies, you know the meaning.

Moral: Nice try.

Can men and women ever be friends?

Q. Whether a tender Friendship between two Persons of a different Sex can be innocent?

A. I look upon the groundless suspicions so common in relation to matters of this nature as base as they are wicked, and chiefly owing to the vice and lewdness of the age, which makes some persons believe all the world as wicked as themselves. The gentleman who proposes this question seems of a far different character, and one who deserves that happiness which he mentions — for whose satisfaction, or theirs who desire it, we affirm that such a friendship is not only innocent but commendable, and as advantageous as delightful. A strict union of souls, as has been formerly asserted, is the essence of friendship. Souls have no sexes, nor while those only are concerned can anything that’s criminal intrude. ’Tis a conversation truly angelical, and has so many charms in it that the friendships between man and man deserve not to be compared with it. The very souls of the fair sex, as well as their bodies, seem to have a softer turn than those of men, while we reckon ourselves possessors of a more solid judgment and stronger reason, or rather may with more justice pretend to greater experience and more advantages to improve our minds. Nor can anything on earth give a greater or purer pleasure than communicating such knowledge to a capable person, who — if of another sex — by the charms of her conversation inexpressibly sweetens the pleasant labors, and by the advantage of a fine mind and good genius often starts such notions as the instructor himself would otherwise never have thought of. All the fear is lest the friendship should in time degenerate, and the body come in for a share with the soul, as it did among Boccalin’s poetesses and virtuosis, which, if it once does, farewell friendship and most of the happiness arising from it.

Moral: Yes. In fact, it beats the bromance. Souls don’t have genders, but men think they have better judgment than the ladies, when all they really have is more education and experience. That means gents get to feel superior teaching the ladies, which is all kinds of charming, and that the ladies figure stuff out with their native wit that wouldn’t occur to the over-educated men. Just don’t let it get complicated.

Masturbation. Bad?

Q. What was the Sin of Onan, whether ’tis possible to be guilty of it now, etc.?

A. We shall rather choose for obvious reasons to propose the question in the following terms, wherein any observing man may find all his doubts on this subject modestly and fairly answered.

Parenthetical Moral: We had to cut most of your question, filthy Querist! You’ll find it below, shorn of obscenities. While we’re feeling oracular, some predictions:

1. Centuries from now, a comedy will preserve mastery of its domain by censoring this unnamed activity while making it a crucial plot point, and it will do so almost as deftly as we have here.

2. The unplumbed depths of a future tragedy starring one Mr. B. Willis shall be plumbed thanks to our comments.

Q. Wherein consists the moral turpitude or natural evil of the pleasures of what some have called the Sixth Sense?

A. The reason of the question is this, as has been excellently and closely discoursed between two learned men on this subject, because abstracted acts of this nature, as lascivious embraces and others whereto the present difficulty more immediately relates, seem to have no malice against God or our neighbour. The case of Onan being (as ’tis acknowledged by all) different from that of single men, I say those acts may be thought neither to injure our neighbour nor destroy society as adultery and fornication do. Wherein then consists their natural evil? We answer, it consists in the same point that all other evils do, namely, in deviation from a rule or law, and that the law of Nature, as well as the positive laws of God.

Now that such abstracted acts as these before mentioned are contrary to the laws of Nature is evident from this reason: The end for which Nature has given this perception whereof we discourse, is for the propagation of mankind; which if employed for any other end, ’tis plainly abused, and therefore unnatural, if anything is so. ’Tis besides forbidden in the 7th Commandment, which inhibits all manner of unchastity, and even the Romans abhorred it, who were far from being their most modest writers.

As to whatever of this nature, may be accidental or involuntary, both as to the act and causes of it, as diet, etc., so far as ’tis involuntary, it cannot be reckoned sinful. But if otherwise, no pretended necessity can excuse in that any more than any other sin.

Moral: Onan was supposed to impregnate his dead brother’s wife and he kept pulling out and spilling his seed on the floor instead. At least you’re better than him and the fornicators. That’s really all that can be said for you. Look: God gave you a sixth sense, a mode of perception that exists to make you make babies. The wet dreams you can’t help. God thinks you’re gross, but He’ll cope. If you’re employing “it” for any other “end,” however, don’t expect a happy ending.

Lesbianism. Real?

Q. Whether ’tis possible for one woman to love another as passionately and constantly as if the love were between different sexes?

A. As constantly they soon may, but as passionately how should they, unless they’re of the race of Tiresias?

Moral: How would that work, exactly?

Help! Got pregnant in my sleep! Can I get an abortion?

Q: Gentlemen, I am a young Gentlewoman, in the very prime of my youth, and if my glass flatter me not tolerably handsome, likewise co-heiress of a very fair Estate; there being but two sisters of us to enjoy what my aged Father’s many years industry hath acquired. Though my father hath ever shown himself lovingly tender, yet he hath ever had so great an awe over us, that we never durst give him the least suspicion of any ill conduct in our behavior, he often assuring us that nothing should so soon quench the Flame of his paternal love as our deviation from the strict rules of pure chastity and its handmaid modesty. Now, to my utter ruin and eternal shame (if anything unknowingly committed may be termed shameful) I am with child. How, when, where and by whom, to my greatest grief I know not, but this alas I know too well, that the hour wherein my father hears of it, I am disinherited of his Estate, banished his love, etc. Gentlemen I earnestly implore you to give me some relief by solving these two queries.

1. Whether if it is possible for a woman so carnally to know a man in her sleep as to conceive, for I am sure this and no other way I was got with child?

2. Whether it may be lawful to use means to put a stop to this growing mischief, and kill it in the embryo; this being the only way to avert the thunderclap of my father’s indignation.

A: To the first question, Madam, we are very positive that you are luckily mistaken, for the thing is absolutely impossible if you know nothing of it; indeed we have an account of a widow that made such a pretence, and that might have better credit than a maid, who can have no plea, but dead drunk, or in some swooning fit, and our Physicians will hardly allow a possibility of the thing then. So that you may set your heart at rest, and think no more of the matter, unless for your diversion.

As to the second question, such practices are murder, and those that are so unhappy as to come under such circumstances, if they use the forementioned means, will certainly one day find the remedy worse than the disease. There are wiser methods to be taken in such cases, as a small journey and a confidant. And afterwards such a pious and good life as may redress such an heavy misfortune.

Moral: Great news. If you were asleep, you couldn’t have gotten pregnant, so don’t worry your pretty little head about it anymore unless it’s fun for you. If you’re lying, which you totally are, take a nice long trip with someone you trust. Deliver, rinse and repent.

[This isn’t the Mercury’s last word on abortion. More on that during a Very Special Reproduction edition.]

My wife is pregnant and so am I! A tale of sympathetic pregnancy.

Q. Upon my wife’s conception I am immediately sick, and so continue every morning ‘till she is quick, and bear equal pain with her whilst in labour. This is matter of fact, pray your opinion of the reason thereof?

A. Agues and several diseases the learned say are cured by transplantation, of which divers authors have writ; and some would from hence infer a reason for such instances as this in the question, but we think it foreign to the matter. Sir Kenelm Digby has very learnedly treated on the nature of sympathy betwixt the particulars of one and the same principle, which comes very near the question, and to which we refer our querist. Our thoughts upon it are these: That the semen has potentially an idea of every particular part of humanity, and the imagination in the generative crisis may be so great as to fix the idea a great deal stronger than naturally it is, even so far as to retain a sensible communication to or from the whole mass from whence it is separated, so that whether the whole or the part suffers, the same is communicated to the other by the aforesaid sense of the imaginary impression.

Moral: Perchance you think sharing pains with your wife bespeaks some sort of sacred extrasensory bond (a seventh sense, if you like). Possibly you imagine that you and she are forming one flesh in fact, not merely in faith — that not merely your souls but your nervous systems have merged. You are feeling with her, sharing the ultimate connubial creative experience, helping her shoulder the burden of Eve’s curse.

You’re wrong, but only in part. You’re not communing with your wife, you’re in fact communing with your semen, the imaginative capacity of which might be stronger than usual. It’s calling to you from inside her. Action at a distance, friend. It’s a thing.

¹ Not to be confused with “Denton.”

² Spelling and punctuation for all entries has been modernized.

Read the first installment of “Dear Athenian Mercury.”

Lili Loofbourow is a writer living in Oakland. She blogs as Millicent over here.

Top picture courtesy of the British Museum.