'Scott Pilgrim' Versus Itself

by Mike Barthel

I don’t want to be the guy arguing that a movie adaptation of a comic book doesn’t do justice to the original comic. I especially don’t want to be the one doing that about Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World, because there have already been dark accusations about it being too fanboyish, and I am most definitely a fanboy for Scott Pilgrim the comic book. But the little things that bug me about the movie all ultimately feed into one big complaint: the wonderful treatment of female characters in the comic book gets lost in the transition to the big screen. It’s what happens when you make a big action-filled summer film. But it’s not good that this requires the female characters and their particular relationships to be swept under the rug.

Let me back up, though, and explain why I love the comic so much, because I think you may be missing out on something pretty wonderful if you’re dismissing the movie as another twee Michael Cera vehicle. Scott Pilgrim the comic was written by a guy named Bryan Lee O’Malley and published in six manga-sized volumes between 2004 and 2010. Though taking a lot of structural cues from Japanese comics-see Dan Kois’ wonderful explanation here, which is absolutely vital and way more knowledgeable about Scott Pilgrim’s relationship to comics than I can be-it’s strikingly different from other indie/art comics, and even unlike the superhero comics that generally get made into big-screen adaptations (it’s comparable more to Archie, since none of the characters are super and they’re all stuck permanently in adolescence).

The main character, Scott Pilgrim, is a recent college graduate who lives in a one-bed apartment in Toronto with his gay roommate, plays bass in a band called Sex Bob-omb, and falls in love with a cute American girl named Ramona Flowers who dyes her hair and is awesome.

The story isn’t about super powers or life-or-death situations or the fate of the world. It’s about love, and being young, and it won an award for being the best humor comic of 2010, because it is hilarious. The people it’s about aren’t particularly exceptional, and the things they go through-hooking up, trying to find jobs, dealing with their past-aren’t either. It’s just that the reality in their universe makes their normal actions metaphorically resonant in wonderful and complex ways.

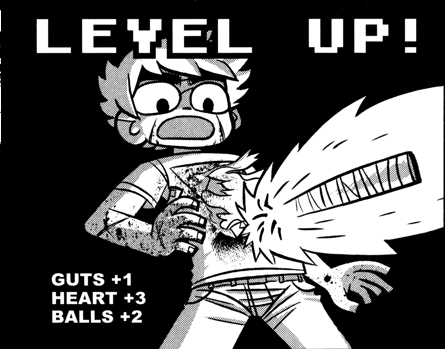

The central conceit of Scott Pilgrim is this: what if the imaginary realities of the pop culture a generation grew up with were reflected in physical reality? So, for instance, the generation that grew up with manga and video games resolved its emotional disputes through kung-fu fights, and when someone was defeated they turned into a handful of coins? What if your emotional maturation were reflected in visible improvements in your personal stats (“Heart +1,” etc.) and being a vegan gave you super powers? What if music was so powerful and so important that really good bands could cause explosions with the force of their rocking?

And, most importantly, what if this was all absolutely normal-so normal that when someone turns into coins or plucks a sword out of their chests or trashes a concert hall with their performance, everyone was kind of bored and disappointed and wandered off to get pizza?

Games are an essentially new art form that only that particular generation-O’Malley’s generation-have grown up knowing. So if movies or TV changed the way earlier generations experienced the world, so must video games have changed how this generation experiences the world.

The physical presence of game mechanics in the midst of one dude’s post-college emotional malaise makes sense because it’s an accurate externalization of his thought process. There are no thought balloons in Scott Pilgrim-either someone speaks, or we get a picture of their thoughts. Thoughts never come in words, only in pictures, and that, to me, seems like a good way of representing how confused predults haphazardly try and gain control of their lives.

What makes Scott Pilgrim not just a good comic but a great piece of art (seriously!) is that it doesn’t just find a series of fun stories to tell within this reality, but tells one story (its six books constitute the entirety of the series, and tell one continuous narrative) that explores the consequences of this outlook for the people afflicted by it-their ability to connect with each other, and to accept the non-metaphorical parts of reality that can’t be resolved through boss fights.

While in the first book the series looks to be about a straightforward progression of fights for Ramona’s love, Ramona is not only given agency (!!!) but emotional issues of her own to deal with, and by the fourth volume, the series characters have all began to sunk into a collective malaise that will feel very, very familiar to anyone who lived through a shiftless mid-twenties. The final volume unexpectedly climaxes with a fight not between Scott and one of Ramona’s evil exes, but between Scott and himself-and he only wins by losing, allowing the romantic self-image of himself as a hero to coexist with the reality that we’re never always victims or victors; we’re victimizers, too.

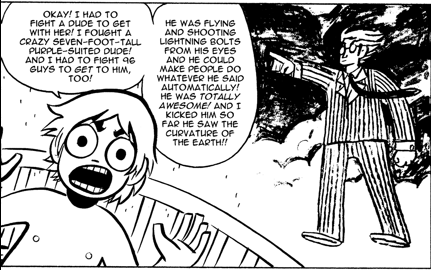

This progression spans the length of the series. In the third book, Ramona finds out that Scott and the band’s drummer, Kim, dated in high school. When she asks Scott for the details, Scott demurs, but when Ramona insists, he bursts out with a story about having to fight a “crazy seven-foot-tall purple-suited dude” (see above). Ramona takes this as sarcasm, but we know from the opening of the second book that he does, in fact, have a memory of fighting said dude (in an homage to the classic NES game River City Ransom) for Kim.

In the final volume, though, an epicly moping Scott goes to visit Kim in the country, where she breaks him out of his funk by reminding him that he didn’t fight a giant dude-he just punched a defenseless kid named Simon Lee who had only held hands with the object of his affection.

Scott’s coming to terms with this-with the fact that he had built up prime examples of his own dickishness into self-defining stories of heroism-provides one emotional climax. But the other comes when Ramona has a similar revelation in the midst of the final boss fight against her seventh evil ex, Gideon.

Though it’s easy to think of Ramona as a classic manic pixie dream girl (the NYT review even compares her character, cringingly, to ur-MPDG Kate Winslet in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), she’s just as problematic a character as Scott. It’s no accident, after all, that all of her exes were willing to band together into a league dedicated to wrecking her future relationships. She burned them all pretty bad.

In the end, it turns out Ramona’s just been on her own epic mope alone in the country. She hasn’t been running from man to man, she been dealing with her own shit, because healthy relationships aren’t about one person saving the other or making them better-they’re about two people filling in the gaps where their partner needs a hand, and being open enough to allow that to happen. Ramona only comes back to Scott after she figures this out, and together they can defeat impediments to their mutual happiness.

What’s great about Scott Pilgrim is that it turns its gaze resolutely outward. There are lots of other things going on in Scott Pilgrim besides what’s happening to Scott, and often, these are more important things. The central quest, Scott’s attempt to defeat Ramona’s seven evil exes (and, though we don’t realize it until the end, Ramona’s quest not to let that interference dissuade her from opening up to Scott, and to deal with Scott’s own romantic past), is a metaphor not only for the surprising and corrosive effects of your romantic past on your romantic present, but the ways in which pop-borne images of romance and conflict can get in the way of living a full life. The triumph at the end of the series is less that Scott and Ramona have defeated the final boss than that they have both seen these illusions as illusions (rendered in pixel art and textese) and are able to face each other as full, flawed human beings.

The problem with the movie is… well, in the simplest terms, it doesn’t pass the Bechdel test. For a movie based on an art comic, this is weird, to say the least. And it’s absolutely not true about the comic. One of the best things about it is that Scott often seems like a minor character in the context of his friends, all of whom are living much richer and fuller lives than he is. Female characters form friendships, male characters come out of the closet off-screen, and ex-girlfriends move on. The comic makes a joke about this: Scott’s self-centeredness causes him to assume, as fiction readers do, that nothing important happens without him around. But, of course, things do all the time.

They don’t, though, in the movie. Again, part of this is certainly structural. Movies just have less space available to them than do comics, and clearly they had to get through all seven exes. But that necessity spins out into other necessities: the main character has to be male, there has to be a clear romantic tension and resolution, there can’t be distractions from side characters. And though a lot of the great things about the comic are preserved, that sense of outward focus and of ladies existing without reference to dudes (or dudes without reference to ladies, honestly) absolutely vanishes.

I come here not to trash summer action movies; after all, I am probably going to go see The Expendables while my girlfriend is at a bridal shower I am confusingly not invited to. (I am thinking of it as my own little gender roles party!) But the process of adaptation has a way of revealing the essence of a medium. What Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World shows is just how small movies are.

Any narrative has to be cut to the bone; any visual element included for aesthetic purposes necessarily obscures a gesture or a shot that could have revealed something about character or context. And these huge differences between movies and comics speak back to Scott Pilgrim’s central message about the power of pop culture to shape our understanding of the world. Might someone whose reality has been shaped by the slower progression of a comic have less expectation of sudden, dramatic change than someone whose pop culture diet was primarily movies and goal-oriented video games? Scott and Ramona’s maturation mirrors the maturation of games themselves from simple 8-bit shooters to sprawling virtual worlds. The side-scrolling progression of the initial phase of their romance (go through each stage, beat the boss, go on to the next stage) turns out to be insufficient and unrewarding; it falls apart when faced with reality. So something new has to come along, something more like a sandbox game or an RPG where you’re free to explore and build up experience gradually before encountering big emotional moments on your own terms.

I’m not going to argue here that video games or comics contain more positive depictions of women than do movies, because that would be crazy. Rather: they could. Movies are old enough and big enough now that their artistic expectations have become indistinguishable from their technical features; somehow, the need to have a male protagonist is as unavoidable as keeping a film under two hours, or lining the sound up with the visuals. Games and comics are still relatively new, and relatively small, and still doing a lot of internal thinking about how they can and could work. As those get figured out, they’ll inevitably get wedded to aesthetic features, and harden into conventions that become self-reinforcing as audience expectation determines what will and won’t be rewarding. Scott Pilgrim represents one particular argument about how comics could work, and it’s an argument I like. But mostly, I like that it’s having this argument. That’s not really present in Scott Pilgrim the movie, and while I understand how that happens, and while I did enjoy it, I’m not entirely happy about it.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this column stated something really kind of hilarious, involving an invented heterosexual marriage of Dykes To Watch Out For author Bechdel. The copy desk regrets being really tired on a Friday afternoon. Our apologies.

Mike Barthel has written about pop music for a bunch of places, mostly Idolator and Flagpole, and is currently doing so for the Portland Mercury and Color magazine. He continues to have a Tumblr and be a grad student in Seattle.