Enthusiasms: 'The Singles Club'

by Sarah Jaffe

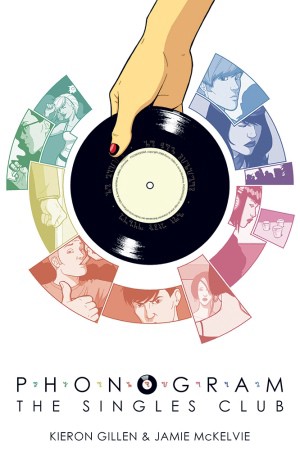

Phonogram is a comic about how music is magic. Literally. There are two volumes now: the first, Rue Britannia, about the death of and nostalgia for Britpop, and, more recently, The Singles Club.

Set in a British nightclub, each single issue of The Singles Club focuses on one person, one experience of the same night, which is both an ordinary night in a club and somehow extraordinary for each of them. Each single issue here is a complete story, based loosely around a song-the “Singles” of the title-and what that song means. Each one is a slightly different capital-M Metaphor for what pop music really does to us. Music affects each character in a different way-most of them are “Phonomancers”; in the world of the comic, they’re magicians who use pop songs to create their magic.

The nightclub has three rules: No Male Singers, You Must Dance, and No Magic. Of course all of those rules are broken, but particularly the third one, since magic here is not only something that the characters do but something that happens to them. The magic in pop songs is never quite under their control. And it veers here between Metaphor and actual fact.

The single issue has been ripe for comics creators to play with in recent years, and writer Kieron Gillen and artist Jamie McKelvie had fun with it in these books, but reading them all through together in collected form in The Singles Club trade has its own pleasure. The stories build one upon the next, intertwining around one another like bodies on a dancefloor, so that the whole comic is not just about the love of dancing but is itself a dance-a dance of characters and narratives, of art and words, of meaning and layers and feelings and memories.

Phonogram is part of a loose group of books that I recommend to my non-comics friends as much as my comics friends. Because we are a different breed, us comics folks, we like our pop culture a little madder than most. So many of the books usually recommended to non-comics fans, though, are autobiography spilled beautifully onto a page with liberal helpings of narration, text to help along the non-comics fan, unused to reading pictures for a story, tracing narrative between panels. But Phonogram isn’t one of those comics-it needs no narration even when it has it, and it’s told as much in moods and feelings-like a pop song-as in a story.

Gillen himself has written about the need to split comics into Art and Story, and why it’s wrong, why comics are more than illustrated prose:

[C]omic reviewers — especially mainstream comic reviewers — tend to dissect art and writing separately, and credit all praise or hatred at the artist or writer respectively…. Which of course, is fair. Their names are on the book, after all. But on another level, it’s totally delusional…..We push and pull one another, and the work which comes out the other end is some strange alloy of our skills, desires and ability to give a toss on any given day… The closest parallel is bands, the other small groups of impassioned individuals gathered together for a larger purpose whose work — even the work which can be clearly originated by one member of the collective — is best analysed as part of the whole.

The best comics don’t allow you to split them apart this way. They carry you along in words and pictures, creating a work that is more than the sum of its parts. Phonogram’s closest companions in the medium are hard to figure out-it has more in common with Scott Pilgrim on one hand or Demo on the other than mainstream comics, though Gillen and McKelvie both have worked on plenty of superhero books. But you don’t need to be a comics person at all to love Phonogram. You just have to enjoy the ride as if it’s the moment watching two people dancing in a blur where you can’t tell which one is which. Or, as the writer himself says (though he and I would probably agree that you should never read a book the way the authors tell you), like a band. Ultimately the dance is what’s worth it.

Comics suffer from the assumption that they are for kids, and that they are not serious. Phonogram glories in not-being-serious and by not being serious-and poking at the layers of seriousness put on by kids-it gets to places that make you feel something. Even if it’s just seriously the need to go dancing. (Go ahead and go. Come back later. We’ll understand.)

In getting at why music is magic it makes an argument for all pop culture, for things that we assume are transient, whether that’s a chart-topping single or youth, sex, heartbreak, a glance across a room or the moment that just the right song hits your ears and you hit the dancefloor and just can’t pretend for one more second that you’re too cool.

Penny is the Phonogram character

who does not just love dancing but personifies it. Her issue begins the series in her own candy-blonde perfect argument for momentary bliss being worth it, every time. Penny (dancing) is a lightning rod and a Rorschach test for the other characters-do they love her, envy her, hate her, ignore her? All the other characters’ feelings toward Penny are their feelings toward the world, their feelings about life.

Penny’s physicality jumps off the page and makes you wish just for a second for the power of cinema to see her move, even though this is the most kinetic I’ve ever seen still pictures. And anyway, you know how she moves, don’t you? You’ve all seen that girl in a club who just doesn’t give a fuck and dances wildly enough to knock the cobwebs off that cliche about dancing like no one’s watching. Penny talks plenty, too, straight to camera (so to speak) but, like Rita Hayworth in the classic Gilda, she can talk and dance at the same time.

Marc comes next, all stillness where Penny is all motion-Marc is stuck in the past and not even Penny’s wild blur can drag him out. But he’s the prettiest thing you’ve ever seen, oh yeah, every guy who’s ever leaned against a wall and been just cool enough doing it that you want to, need to make him move. That he holds your attention by staying there and you can feel his stillness even as you dance. Is he watching you? He’s Jordan Catalano-”I love the way he leans. Like, against things.”

It’s a metaphor for Marc’s whole life-his friendships, relationships and loves happen to him. Other characters have “Phonomancer” names they’ve made up; Marc’s was given to him and he shifts uneasily when the others use it on him. He’s got a pretty boy’s self-pity and self-absorption but for all that a universal problem.

He got his heart broken to the tune of, well, we don’t quite know. All we know is that the song comes on in the club and takes him back into a memory. While the comics are full of songs that we all know, this one is intentionally left out so you can insert your own curse song here, the one that doesn’t just remind you but carries you straight back to that moment that still stabs you in the guts. Because pain can be an old friend just like a song, after all.

“She,” the girl who broke Marc’s heart, doesn’t have a name and that’s usually a bad sign for a character-Token Girl time. But even the “she” in Marc’s head won’t let him blame her for his self-pity and so instead we get the best feminist twist on the Manic Pixie Dream Girl ever. Even though she’s just a memory she calls Marc on his shit, and gives him permission to hurt at the same time. She makes him acknowledge just how much of her he’s made up. No, she’s not real, but our exes never really are.

While Marc clings to his solipsism-”I hurt, therefore I am”-Emily Aster wields the past like a double-edged knife and knows that it’ll cut her. She’s willing to bleed so long as no one sees her flinch, like Tom Waits’ “Romeo is Bleeding” propping himself up so tough. Fittingly her song is by the Knife but when she gets to hear it she’s slipped into her own cursed past and can’t dance properly to it, stumbling over the words and steps. Except Emily knows quite well she cursed herself.

Emily reinvented herself in sharp pain on skin, new clothes and a sleek haircut, selfish sex and plenty of magic. She’s cold and harsh and brittle and yes, strong in her own way and I see myself in her. In both her mirror images, reflecting their hate back at one another in the best panel in the entire comic. Pressed against a mirror giving her old self in the reflection the finger, in the arms of a boy she’ll hatefuck to prove something to her old self-mostly that she’s not her.

The Singles Club is seven issues long and so right in the middle we stop and focus on the DJ booth. On Seth Bingo and Silent Girl, who have created the club night around which the rest of the characters orbit. It’s like watching the pilots of this story for a while, and it’s conceptually the most interesting even though visually the most static. The panels don’t change, like a camera set just to catch what the DJs are up to, and it’s mostly a showcase of how Silent Girl is not actually silent at all. (Once again, the clever Team Phonogram prove their cred as two of the most feminist guys in comics.)

She’s no foil, but instead the only one in the room who really gets it, who really hasn’t put her love for music under a pile of pretensions or fears. Seth wants to ban people from using magic in his club so that he can be the only one wielding it, but Silent Girl gets the best line in the book with “You’re not my vinyl Moses,” reminding Seth why they are there. The visual of the two of them tearing apart the panel to blast the dancefloor with pure pop and all the magic that contains is brilliant. Brilliant.

It acknowledges the parts of the story that are missing in all comics, the things just outside panel borders, and then breaks down those walls. And the double-page spread that follows pulls in all the characters in one of those perfect nightclub moments where everyone is dancing. The one rule that doesn’t get broken: You Must Dance.

We need all the up of “Konichiwa, Bitches” and Seth and Silent to carry us through Laura, though, because Laura’s hurt and need is so close to the surface that she can only cover it up with massive doses of Long Blondes lyrics. Oh yeah, Laura isn’t happy or pretty or going to find an easy solution. She doesn’t even know which solution she wants to find, doesn’t know hate from love, lust from envy. She’s well on her way to being Emily yet she doesn’t even have the wherewithal to create herself a new identity that hasn’t been forged for her-you can’t steal the persona a pop star’s already created without just coming across as ridiculous. Emily looks away from the mirror and doesn’t like the mirror that Laura holds up to her, either.

Yet it’s for Laura that Emily does the one thing all night that might be considered kind, and that itself tells you as much about Laura as it does about Emily. We feel bad for the people who remind us of ourselves. We also hurt the things in ourselves that we see in others. Every minute. Even Emily. Even Laura. Which is why Lloyd and Laura have to cross paths, and have to repel like two magnets wrong side out. The attraction could be there, it could make sense, but not from this side.

Laura has to escape by learning to walk the line between being cruel to others and honest with herself and just maybe there’s more hope for her than Emily, even, as she makes her break, alone, at the end of the night. Most of the Singles Club characters end up finding their solutions alone (the double play of the title-single tracks, single-issue comics that don’t require being read together but play so much better when they are, and single people figuring out that that’s OK). Nobody finds salvation in another person, here. Which makes sense in a way because you can’t share a comic the same way as a piece of music, pressed body to body in a crowded, too-loud room. And this is a story that despite being loaded with music and motion needed to be told in comics.

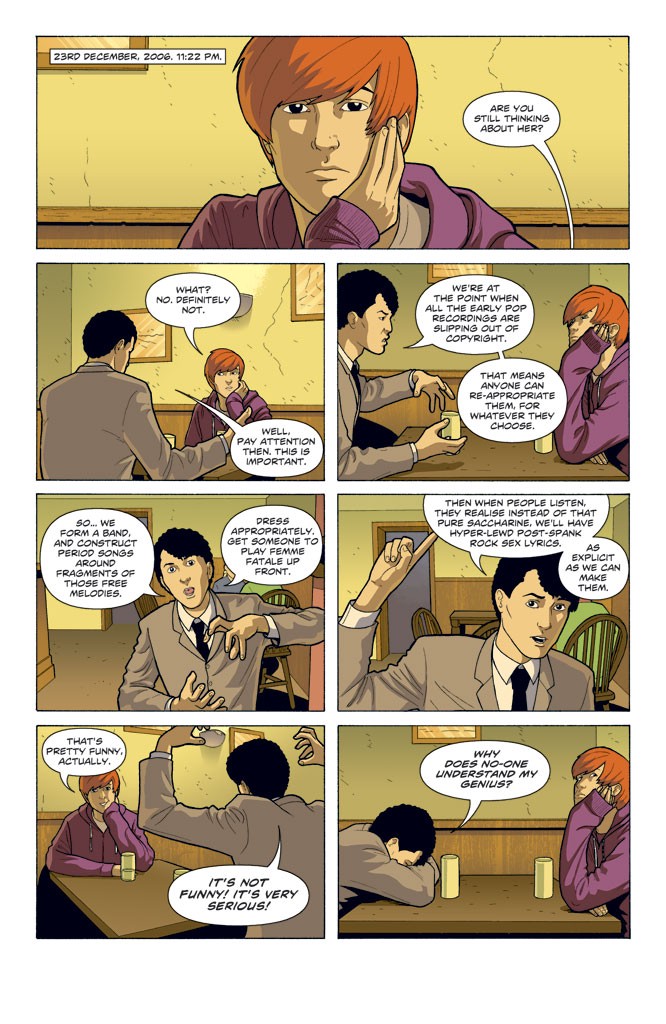

And then Lloyd. Lloyd and Laura need each other and need to reject each other. Lloyd is as much a construction as Laura but where Laura wants to be something, Lloyd wants to make something. He’s angry that no one calls him by his Phonomancer name, the person he’s created, and more angry that no one cares about his brilliant idea. Lloyd’s story is the only one that mostly takes place outside of the club. No, he’s too serious to dance, so he goes home and makes: A ZINE. And Phonogram flirts with fanzine culture to begin with, to the point of the back pages in the single issues being stocked with interviews and rumination on bands, not to mention a song list and notes on all the bands mentioned-and then of course the wonderful Matt Sheret created a zine ABOUT Phonogram, and now this issue of The Singles Club more or less is a zine. But still a comic. If that makes you feel better.

“Wolf Like Me” and Kid-With-Knife end the series and while each comic here is a pop song, a few minutes of entertainment and bliss in a compact package made as pretty as possible for you to love, cry to, and refer to forever, well, this one takes that metaphor and explodes it right in front of you. Oh, you thought the previous issues were perfect singles? Here you go. The issue reads along exactly with the song. The perfect single, indeed.

It’s also the issue that brilliantly captures the populism in pop. You don’t need a fancy grimoire to unlock the magic in a pop song. You just have to feel it. Silent Girl knows this but it is her job, with Seth, to control the secrets and command the room. And David Kohl, the godfather of The Singles Club, the star of Rue Britannia, knows it too and tells Kid-With-Knife, who is the furthest thing from the rest of these hipsleek indie kids, how to do it. “That’s it?”

Start the track, the bleeding-brilliant TV on the Radio record, when Kid realizes it. Realize that this song is shattering the rule against male singers. Realize that somewhere in here this pure-male energy is going to crash into someone else. Take bets on who it is. You may be right. Either way, you’ll love it.

It’s the closest thing to a superhero story in Phonogram and you can feel the rhythm pulsing through each page, each punch, each step. It’s thrilling. It’s magic. He gets it.

The magic isn’t just in the music, really. It’s in all of us. It’s what we add to it. It’s what makes it matter. There’s as much magic in a few words in an email that make it all a little better as on a dancefloor-it’s just a different kind. There’s magic in a first kiss in an alley as much as there is when just the right song is playing.

The magic in the music is what we put into it as much as anything else. And so you don’t need to have a sleek haircut or recognize all these songs (though if you want a tracklist, Kieron Gillen has provided one) or even love comics normally to love this collection. It is what you see in it. As all art should be.

Sarah Jaffe is the Web Ninja at GRITtv with Laura Flanders and Deputy Editor of GlobalComment.com.