Ernest Hemingway Stories As Told By George Plimpton

by Jordan Carr

Since we’re talking about Ernest Hemingway today, as it would be his birthday-here are a few stories from George “And a hot plate!” Plimpton about the man.

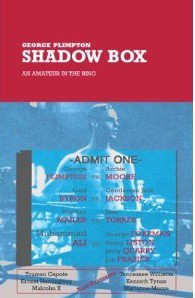

Shadow Box is a book about boxing and literary people, and nobody occupied that nexus quite like Ernest Hemingway. The first scene takes place after Plimpton has just been taken under his wing by boxing trainer George Brown to fight Archie Moore, then the light heavyweight champion of the world. Having heard about this, Ernest gives George a call, asking him to visit at his hotel in New York City where he’s staying with his wife, Mary. Things begin awkwardly:

“Papa,” I asked, “what is the significance of those white birds that sometimes turn up in your, um … sex scenes? I’ve always…”

I mentioned this in a high, cheery voice, as if it were a natural enough matter to come up in conversation; actually it always had puzzled me, especially the white bird that flies out of the gondola in the love scene between the young princess and Colonel Cantwell in Across the River and Into the Trees.

He stopped and whipped around toward me and I could see that I had made a mistake. His whiskers seemed to bristle like an alarmed cat’s. “I suppose you think you can do better,” he shouted at me.

“No, no, Papa,” I said. “Certainly not.”

I noticed how small his eyes had become, suddenly, and bloodshot, as if affected by the flush of rage that showed on his cheekbones, and if I had not been carrying a very excellent picnic hamper of his with some wine left over in it and some cheese, he might well have bulled me off the dock into the bay.

The next day, things were no calmer, and after the Hemingways got involved in a rather contentious argument revolving around the number of lions they had seen on their last African safari, Ernest turned his attention to Plimpton.

He looked at me almost as if he had noticed me for the first time. Since lions were the nub of their dispute, that was the first quick impression-the big-cat character of the large grizzled head turning, the intense curiosity of that first formidable look, all of this compounded by the evident testiness, so that one had the forboding sense of what a gazelle must feel when he looks up to find a lion staring at him over a bush.

Hemingway pushed back his chair. Its legs shrilled on the tile floor and Christobal jumped off the table.

“Let’s see how good you are,” Hemingway said.

I had no idea what he was talking about. But then, as he came around the end of the refectory table, I could see he was assuming a semicrouch, his hands bunched at his waist, and I realized he wanted to spar-he wanted to take a look at George Brown’s pupil.

But of course it was something else, too; he was belligerent now, and he wanted to lash out at someone. Perhaps he remembered my impertinent question about the white bird the day before. I pushed back my chair and stood to face him-my hands up in front of my chin-and I put on a tremendous smile to indicate I hoped he’d calm down and all of this was going to be in good fun. I put out my left hand, flicking it an inch or so off his whiskers, to keep him away, and he stepped past quickly. His hands were rolled at belt level, and one of them came up in a left hook and I was banged hard alongside the head, past my guard, and I staggered backward and my chair went over. I felt the sympathetic response at work, the tears beginning to spring out; my smile wobbled; I moved around behind the fallen chair, keeping it between us, and I leaned over it and kept my left out. I noticed once again how small the eyes were in his face, and furious like a pig’s, and yet how surprising and utterly unnatural it would have been actually to hit out those whiskers.

So that’s how he had fun with his friends-by punching them in the face. Good times. Also, there’s the time he met Tennessee Williams in Cuba in 1960. Plimpton assesses how the nervous, eager to impress playwright did in their first meeting:

I don’t think the meeting went very well for him. Tennessee began by saying that when he lived in Key West he had known Hemingway’s former wife Pauline.

“How did she die?” Tennessee suddenly asked.

Hemingway peered at him in the gloom After a while he offered an explanation that seemed lifted from a freshman Hemingway parody: “She died and then she was dead.”

A silence ensued.

Hemingway later offered his take on Williams to Plimpton:

I think Hemingway was slightly puzzled by the encounter… He was thinking about Tennessee. “Not a predictable sort of man,” he said. “Is he the commodore of something … that yachting cap?”

I said I didn’t know. I doubted it.

“Goddamn good playwright,” Hemingway said.