Ernest Hemingway, Lady-Man, Would Be 111 Today

by Jane Hu

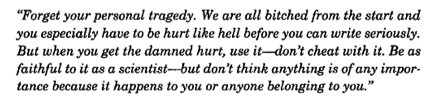

Ernest Hemingway wrote what might become his most-quoted lines in a letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald, shortly after the publication of Tender is the Night. Hemingway called Fitzgerald “bitched” for having married Zelda Sayre, “someone who was jealous of your work, wants to compete with you and ruins you.” Leave it to Hemingway to describe creative impotency and emotional indulgence in overtly female terms.

The 30s, from our vantage point, seem so rife with modernist angst and Prufrockian figures of melancholy and embarrassed masculinity. All in all, perfect characters for castration theory to uncover man’s inner bitch. Nonetheless, Hemingway does not dismiss a writer’s propensity “to hurt like hell,” but welcomes the “damned hurt” in service of literary practice. At the same time, you see him urging for a level of objectivity: one must dissect one’s pain-and thus one’s art-like a “scientist.”

T. S. Eliot notes in “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1919) the difference between “the man who suffers and the mind which creates.” Similarly, Gertrude Stein separates inauthentic art (a form of self-expression) with true art (narratives that exceeded the self).

And so always it is true that the master-piece has nothing to do with human nature or with identity, it has to do with the human mind and the entity that is with a thing in itself and not in relation. The moment it is in relation it is common knowledge and anybody can feel and know it and it is not a masterpiece.

This divide between sappy, dismissible schlock and transcendental high art rings of Columbia comp lit prof Andreas Huyssen’s infamous argument [PDF] that woman was “modernism’s Other” and, by default, the producer of mass culture-as opposed to men’s “real, authentic culture.”

Gosh, the strain for male writers to achieve dispassionate greatness must have weighed so heavily!

It’s hard to say if Fitzgerald took Hemingway’s advice… because a lot of Hemingway’s own male characters are wounded, world-weary, tender souls themselves. Jake Barnes and Frederic Henry may keep up a stoic exterior but do not tell me you did not cry when Jake and Brett take that final taxi ride. Or when Henry walks back to the hotel alone. In the rain.

Even while Hemingway was advocating for objectivity, it’s not like he ever succeeded himself. His style mimicked a reporterly aesthetic, but his plot omissions also highlighted emotional significance. Hemingway never tells Jake to “Get over it, bitch,” because that’s never the point. Jake’s victimization, disempowerment, paralyzing hurt-all important and necessary.

Maybe Hemingway was reacting badly to Fitzgerald’s feminization of Dick Diver in Tender is the Night-Dick, who gives up his intellectual pursuits in service of a girl. But I don’t doubt that Jake would do the same for Brett in a heartbeat.