Yeah, It's Cold

Image: Jonas Bengtsson via Flickr

“It’s really cold. What the hell am I supposed to do?” —Cold Carl

You think this is cold? I grew up in New England. I didn’t even see the sun until 1981. I don’t think ever came out. We had a large frozen hole in the sky for a sun. Instead of sunlight, it shone down gray streaks of pain. I didn’t even know there were colors other than gray until I was 14, Carl. I thought everything existed in a monochromatic, lifeless pile of endless snow. We had no cable TV or answering machines until I was in high school. For fun, we shivered. When we got bored shivering, we split wood. So many joyful hours of my New England childhood were spent splitting wood. And sobbing ice cubes out into the gray.

They hadn’t even invented terms like ‘Arctic Vortex’ or ‘Bomb Cyclone,’ Carl. Bomb Cyclone was called Thursday. You took the Arctic Vortex to the prom. This is nothing, Carl. My 5th Birthday was during the blizzard of ‘78. We couldn’t have a birthday party because all my friends were buried in frozen snow drifts. We had to wait until those thawed in May. Then I got a blue dinosaur. This was before Star Wars ever came out, so blue dinosaurs were as good as it got, Carl. And we certainly didn’t have days to worry about big storms. They would come out of nowhere, dump snow on you and your family and leave you for dead. And that was all before breakfast.

Aberdeen, Maryland, to New York City, January 1, 2018

★★★★ The thermometer outside the kitchen window had not reached the halfway mark between the 10 and the 20. The actual snows of yesteryear, the faint dusting from two mornings ago, held to the rocks and the leaves on the ground. A mockingbird, of all things, had come down from the fields to join the juncos and finches, jays and cardinals, in the shadow of the woods. It perched on the electric birdbath, the white badges on its wings fluffed out to startling proportions. A woodpecker’s crown gleamed like red satin. The cold got into the pancakes as the dining room, outthrust from the house into the freezing world, betrayed its long-ago origins as a mere screened porch. Trees and sun laid dense narrow stripes across the highway for a while. Outside the first rest stop, gulls huddled low on the flattened brown grass. The industrial plumes over New Jersey turned rich purple in the late sun, and the backs of the highway signs were molten gold; the front faces of billboards surrendered their messages to the shine. The oncoming city flared brass and silver. Inside it, down in the streets, all was darkness and salt crust and frigid wind. The chill worked its way into bare fingers holding a shopping basket inside the Fairway, and it cut through gloves on the walk back, with the burn of oncoming frostbite. The kitchen floor was so cold underfoot it was necessary to stand on a towel to cook dinner.

★★★★ The thermometer outside the kitchen window had not reached the halfway mark between the 10 and the 20. The actual snows of yesteryear, the faint dusting from two mornings ago, held to the rocks and the leaves on the ground. A mockingbird, of all things, had come down from the fields to join the juncos and finches, jays and cardinals, in the shadow of the woods. It perched on the electric birdbath, the white badges on its wings fluffed out to startling proportions. A woodpecker’s crown gleamed like red satin. The cold got into the pancakes as the dining room, outthrust from the house into the freezing world, betrayed its long-ago origins as a mere screened porch. Trees and sun laid dense narrow stripes across the highway for a while. Outside the first rest stop, gulls huddled low on the flattened brown grass. The industrial plumes over New Jersey turned rich purple in the late sun, and the backs of the highway signs were molten gold; the front faces of billboards surrendered their messages to the shine. The oncoming city flared brass and silver. Inside it, down in the streets, all was darkness and salt crust and frigid wind. The chill worked its way into bare fingers holding a shopping basket inside the Fairway, and it cut through gloves on the walk back, with the burn of oncoming frostbite. The kitchen floor was so cold underfoot it was necessary to stand on a towel to cook dinner.

Rose Madder, the Pinky Red of Stephen King's Worst Novel and Hieronymus Bosch's Perverted Playground

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Stephen King’s 30th novel, Rose Madder, starts with a miscarriage. A woman named Rose sits on the floor bleeding from her womb as a man (her crooked cop husband) menaces somewhere in the shadowy background. He’s a villain built of “empty eyes” and hard fists, a man so aggressively racist, homophobic, and violent that to a 2018 reader he feels like an overindulgent parody of toxic masculinity. Later, after Rose has escaped her abuser (or so she thinks), she’ll find a magic painting leaning against a dusty shelf on the floor of a pawnshop. She buys the painting and becomes obsessed with its female subject.

The mystical artwork shows a blonde with a braid, standing on a grassy knoll, facing away from the viewer, her arm adorned with a gold torc and her body wrapped in the loose folds of a vivid pink-purple (rose madder) chiton. The woman in the picture is strong, while Rose is meek. The woman is angry, while Rose is cowering. Rose will come to call her doppelgänger Rose Madder after the textile dye used to color her dress (made from the roots of the Rubia tinctorum—common madder—plant) and her imagined personality—she’s so much like Rose, but madder.

This weird novel was published in 1995, at the “end of King’s fourth major arc: one that focuses on gender and violence,” according to James Smythe at The Guardian, who calls the book “sloppy and ill-thought-out.” He’s not wrong; it really isn’t King’s best work, and he damn well knows it. But I’m a sucker for stories about artworks and performed femininity, and this clunky novel is about both. From the moment we meet her, Rose is a bloody heroine, leaking red and seeing black. An everywoman, womb-empty and ever-wounded.

The Art of "Friendship"

Image: Wrote via Flickr

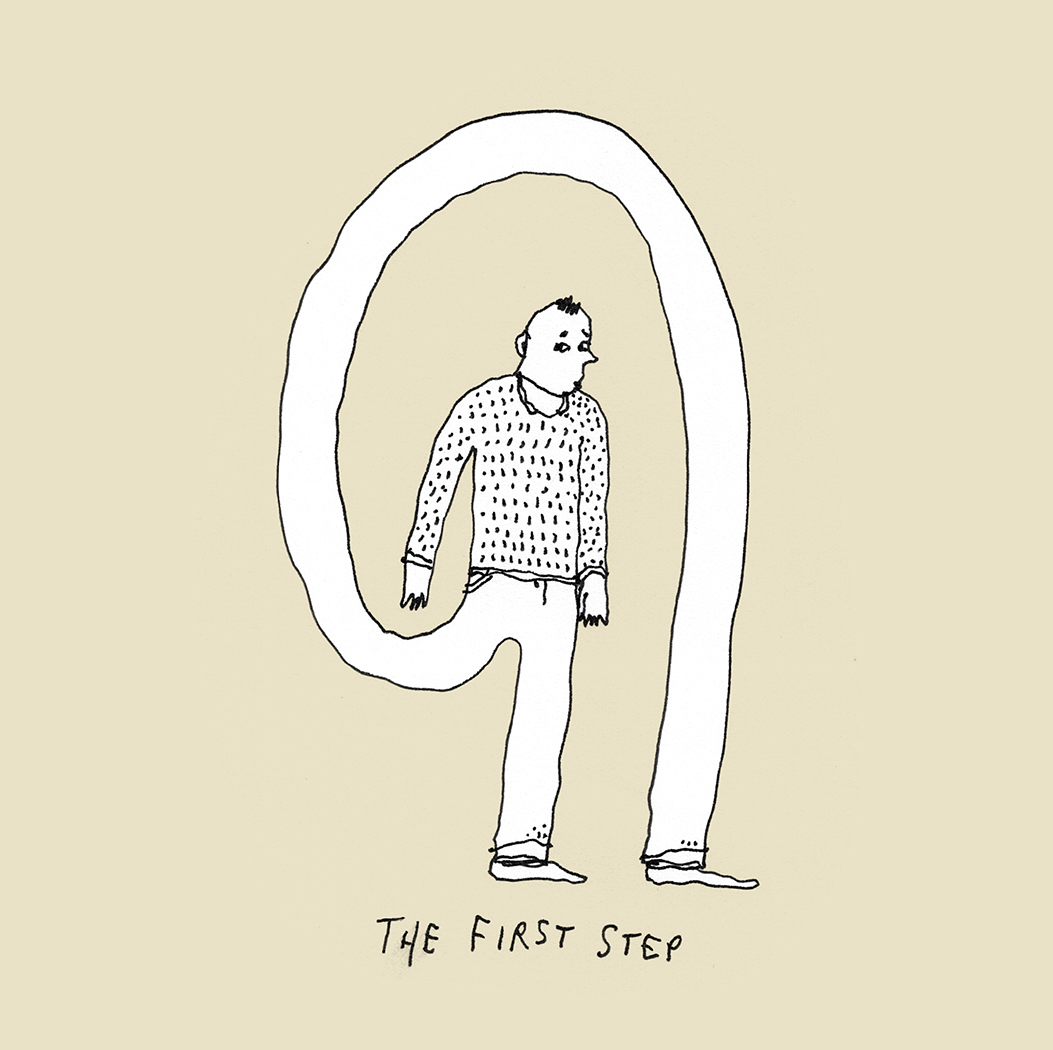

A lot of people in my life exist between “my favorite person” and “my enemy.” Tons. Most of the people I know. Some teeter more towards “favorite person” and they include “people I admire,” “people who’ve nicely told me I have something in my teeth,” and “fellow fans of Dolly Parton.” Then there are people on the other end of the spectrum, like the woman on twitter who keeps following me so I follow her back and then she unfollows me, which I suspect is a weird power-ratio thing she has going for her. The point is is that people span the spectrum and 98% of those people, the ones in the middle don’t need you to detail where exactly they fall.

And in not disclosing exactly where they fall, you have taken the first step in mastering the art of fake friendship. Congratulations. Have some cucumber mint water and relax. First of all, dispel from your mind that fake friendships are bad. They aren’t! You’re confusing them with performative friendships which live on Instagram and in the way-too-loud-for-how-funny-that-joke-was laughs of two supposed BFFs. Performative friendships let onlookers know the individuals are doing alright, great in fact, incredible actually. They’re an outward display. Fake friendships however are private contracts you enter into with another person where you both agree to just be civil. Historically fake friendships are what we often just call “being nice.”

My Name

Image: Quinn Dombrowski via Flickr

If you know me, and chances are you do not, you’ve probably heard me say “I’m from the ’90s.” This one statement encompasses all you need to hear to get to the center of who I am. Of course, you need to know what I mean, which is not at all clear from that statement, but, being from the ’90s, I’m also often averse to explaining myself. Allow me to explain.

“I’m from the ’90s” is a blanket statement of authenticity, as opposed to being, well, not from the ’90s. It’s a joke insofar as everything I say is, but it also tells you a lot about me. It’s not ironic, so much as it is both a point of pride (I am authentic) and a point of self-deprecation (authenticity is bullshit). I am self-deprecating not because I am from the ’90s but because I am from Pittsburgh.

A general observation: people from Pittsburgh and from the ’90s (meaning the 25 people I know and grew up with) are so focused on “being themselves” that we often are stubborn about things like success. Being successful must, in some way, be evidence of having sold out, of having diluted your essence, of having well, failed yourself in some way. I never bought into this observation all the way, even though it is, in fact, my own observation, but I have known plenty of people just like this: smart, artistic characters who never try too hard because trying too hard is evidence that you care, and caring is like, whatever, man.

Family Stories

Image: brianna.lehman via Flickr

The end of the year is a time for family, and, therefore, a time for family stories. You know the type—the stories trotted out every year by the same relatives; the stories with punchlines as rote as the dishes served at the family dinner table. Remember your uncle, who owned the candy store, or your Aunt’s trip to Switzerland, or the cousin who almost went pro? These are the stories told and retold, the stories families slip into and envelop themselves in. They are also, often, fake—or at least loose with the truth.

This process happens naturally, stretched over time and obscured by generational shifts. Something happens to someone, something worthy of telling others, which officially makes it a story. The story of that something spreads, first laterally among contemporaries, then longitudinally, from old to young. The process repeats until the principals are dead and only the story, and the next generation, remain.

That the facts of the matter get displaced in this process is understandable, and reflective of our faculties. We are all aware, thanks to true-crime podcasts, of human-memory’s unfortunate fallibility. And we have all been guilty, regarding both our own stories and those we hear secondhand, of embellishment for narrative affect. The passage of time makes a story’s truth harder to confirm, but so does the nature of stories themselves. Who would want to ruin a good redemptive arch, or forgo a metaphorically rich detail, due to the pesky interference of reality?

Playing Pretend

Image: Denisen Family via Flickr

Is pretend fake? I thought so, but now I’m not so sure. It depends, I think, on whether you believe that what lives inside our heads is fake. Lots of people do; that’s part of why some people don’t think of things like depression as Real illnesses. “It’s just in your head,” we’re told, of stress-related illness. Just. That’s it. Only in the most complex, least understood part of you.

In college, I had a painful rash across my face for nearly a year. I went to private doctors and research hospitals, desperate to be rid of it. No one could diagnose its cause, so many of them decided it wasn’t Real, despite it being undeniably there, on my face. “It’s just in your head.”

Then I found a beautiful dermatologist on the North Side of Chicago, who handed me a small tube of cream and told me, “Why would it mean any less if the cause is in your head? Your head is part of your body.” I used the tiny tube of cream from the beautiful woman who did not dismiss what she could not immediately understand and the rash disappeared.

The rash was not pretend—my roommates who watched the pain with which I washed my face that year can attest to that. But when I set out to write about my relationship to pretend over the course of my life, I realized that maybe I was wrong to think pretend synonymous with Fake, just because it lives in our heads. Maybe pretend belongs in a different category, somewhere more tangential to Real than to Fake. Somewhere between, say, a human-made lake and an oasis that turns out to be a mirage, or even a hallucination.

The Expert

Image: Sholeh via Flickr

“But am I teaching them anything?” This was the refrain, all fall, in the basement of the English department where we graduate students had been shunted into a series of shared offices. Coming back from class, slumping into an uncomfortable chair, dumping papers on a nondescript desk, getting the question, inevitable, “How’d it go?” and saying fine, and then pausing. Starting again: “But am I teaching them anything?” It wasn’t just that we were teaching Fiction I—or Poetry I, or Creative Nonfiction I—for the first time. It was that so few of us had any teaching experience. (Mine amounted to a single year, directly after college, when I was inflicted on two sections of Freshman English and one section of Sophomore English at a high school in South Texas. The most important lesson communicated in that classroom was the one I learned: don’t cry in front of your students.) It was the fact that I’d never taken an undergraduate fiction workshop and so was unfamiliar with the very class I was now leading. It was the fact that we weren’t sure, actually, that it was possible. Teaching fiction, teaching poetry—could it be done? It was right there in my syllabus: “There is no trick to writing fiction.” How had we learned, we wondered. Had that learning involved any worksheets to which we could now refer?

They Live!

Image: Chris Brown via Flickr

I finally understand why people used to say television rots your brain. It’s because it does!

As President “My Brain Is Good, Actually” Trump ably demonstrates, it’s possible to watch so much filmed media that one loses the ability to distinguish between a camera-ready reality and the other one, the one we inhabit when we’re not staring (or glaring) at a screen. As citizens of a nominal democracy, if President Brainworms believes something it necessarily affects us, whether it’s real or simply a specter conjured by the demons who run cable news; and because Mr. “Actually, My Wife Doesn’t Hate Every Single Second She Spends In My Miserable Presence” can’t parse reality, or even read, it seems this has been the year we’ve collectively lost our ability to, just, like, can, even.

That’s why I picked this year to spend time on something I’d never really spent time on before: I picked up a remote and, goddamnit, I tried to consume movies and television. Results were mixed. While I now understand approximately 30% more of what people talk about, I really do feel like I’ve entered the sunken place. It’s not because film/TV is intrinsically bad, or anything—just that things there are so neatly organized that it’s numbing, like a good narcotic. Sometimes, like when I’m watching “Twin Peaks,” it’s hard to come up for air. To look at the push notifications—no, I don’t know why I keep them on either, although I guess I always wanted a front-row seat to the apocalypse—and return to a place (mental, emotional) where it’s not possible to see where this all leads, or how it ends.