New York City, October 31, 2017

★★★★ The west was delicate violet and one window, and only one, caught a metallic light from the east in an unclassifiable color that would have to be called magenta if it were called anything. The layering plan on the way to school had to include the clone-trooper armor jumpsuit. The sunshine was clear but it was hard to stay out of the shadows long enough for any warmth to settle in. Steam was coming visible out of a grate and blowing along ankle-high. The first wave of daylight trick-or-treaters seemed to be mostly braving it without jackets. When a penthouse apartment door opened to hand out candy, the windows to the rear held the full red sunset, sprawling out beyond the river.

★★★★ The west was delicate violet and one window, and only one, caught a metallic light from the east in an unclassifiable color that would have to be called magenta if it were called anything. The layering plan on the way to school had to include the clone-trooper armor jumpsuit. The sunshine was clear but it was hard to stay out of the shadows long enough for any warmth to settle in. Steam was coming visible out of a grate and blowing along ankle-high. The first wave of daylight trick-or-treaters seemed to be mostly braving it without jackets. When a penthouse apartment door opened to hand out candy, the windows to the rear held the full red sunset, sprawling out beyond the river.

The Triumph of the Quiet Style

Image: super awesome via Flickr

The clearest demonstration of the quiet style—the dominant, most provocative, most interesting aesthetic of our time—is in theater, where Annie Baker created a revolution by slowing everything down, inserting long pauses, setting plays at room temperature. Baker is, in America and for straight plays, the unquestioned superstar playwright of her generation. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 2014 and a MacArthur Grant in 2017. Her success is so sweeping that it’s almost hard to remember how weird her style seemed five or ten years ago, and how much it ran against all the prevailing headwinds of playwriting, which, for decades, had been all about making plays faster, more shocking, edgier.

American plays were already fast-paced (quick cuts, overlapping dialogue) and then, in the 1970s, David Mamet figured out a syncopated style that made them even faster. (“Arrive late, leave early,” is his prescription for writing scenes). Neil LaBute, Mamet’s heir, starts his signature play, Reasons to Be Pretty, with the stage direction: “Two people in their bedroom, already in the middle of it. A nice little fight. Wham!” Edward Albee, the reigning granddaddy of American theater, admitted that he wrote The Goat, a play about a man’s love affair with a farm animal, more or less because he couldn’t think of any taboos left to break.

For Baker, studying playwriting at NYU, the contemporary approach to playwriting was a nightmare—a formula to get your turns and reveals as plentiful and as high up in the script as possible, and all of it about as artistic as working in the pit at Daytona. While in graduate school, she had a breakdown (by her accounting, one of many) and, stuck, declared to her mentor that what she really wanted to do was to write a play about her mom and her mom’s “hippie friends sitting around and talking about spirituality for two hours,” which, to Mamet and her NYU professors, would have been like saying that what she wanted most as a playwright was to make sure that her audience had the right atmosphere for a nice, peaceful nap.

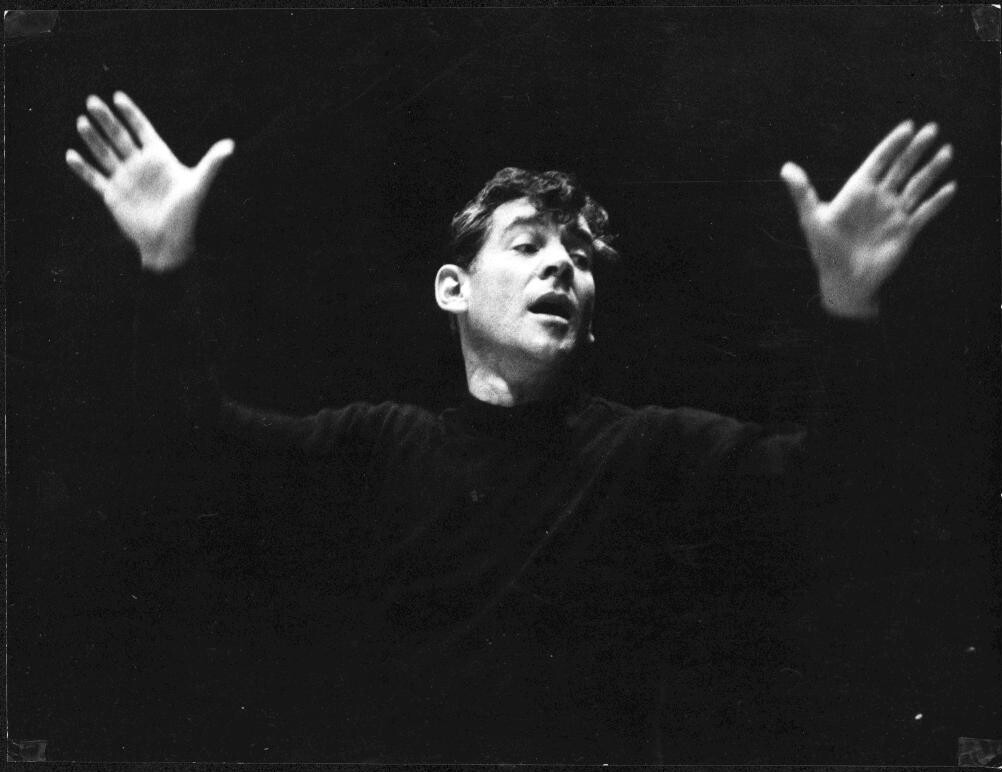

Was Bernstein's 'Age Of Anxiety' Written for 2017?

Image: Leonard Bernstein Collection via Library of Congress

How are you feeling? How are you doing? It has been an interminable few weeks, months, year, etc. A regular stand-up joke I like to tell is saying this year is better than last, but I am barely certain that’s true anymore (it’s not, probably). I spent a few weeks (see also: 10 days) “off the grid,” and while I will never preach the idea of deleting one’s account as a catch-all salve, it is a good thing to do every now and then. Like when you remember you’re supposed to drink water or have a glass of milk before bed. Consider it, is what I’m saying.

It can feel useless writing about classical music at times. On one hand, I worry about sounding elitist, straining to recall anecdotes from my obscure musical background. It’s a niche and privileged interest, one that bears little weight on modern conversations. On the other hand, I think of my brother, a teacher in the middle of the country, whose coworker plays arabesques for her students while they read books of their choice. It’s all relative, is what I’m saying.

70 years ago, poet W. H. Auden published a long-form poem called The Age Of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue about four strangers meeting in a bar in New York City, discussing the way society has changed during the war (“baroque eclogue,” by the way, means this is a pastoral poem written entirely out of dialogue). I confess that I haven’t read the poem, but the phrase “age of anxiety” has certainly seeped into the way we, broadly, as a people, talk about the times, be it the 1940s or the 1960s or the nows. One of posthumous friend of the column Leonard Bernstein’s friends mailed him a copy of the poem, and wrote the following note in the margins:

Why don’t you try a tone poem of ‘Anxiety’? The four themes—their inter-relationship, pairing-off drama—etc. Might make a good thing. And you could do it!

New York City, October 30, 2017

★★★★ The wind groaned and the water splashed on the windows. A hard yellow incoming line on the radar was racing against school dropoff on the clock. The storms were faster, which made the dropoff a victory. Before the children had their shoes on, a rip in the west was showing clear sky. Outside, a few last drops were on the still-rising wind. An umbrella lay utterly broken and squashed dead flat in the roadway of the avenue. The school had dared to open the water-sheeted and leaf-strewn yard as if the morning were normal. The cold and the wet and alcohol had felled one of the men under the scaffold, plainly enough that a passerby had stopped and phoned for help. After he’d stopped shuddering and regained his feet, he argued bloody-mouthed and dismissive with the EMT crew trying to talk him into the ambulance. A stroller, pushed with blind intensity against the cold, ran right through the middle of the discussion and kept going. Another man who knew him pressed the matter: It’s warm in there, he said. In a compromise, he refused the stretcher and trudged, on sodden running shoes, to the ambulance’s side door. The sidewalks were already being blown dry. The layer of clouds held on a while and then broke, leaving rounded, lustrous ones in a blue sky. The wind over the mouth of the coffee lid sent inaudible vibrations down the cup.

★★★★ The wind groaned and the water splashed on the windows. A hard yellow incoming line on the radar was racing against school dropoff on the clock. The storms were faster, which made the dropoff a victory. Before the children had their shoes on, a rip in the west was showing clear sky. Outside, a few last drops were on the still-rising wind. An umbrella lay utterly broken and squashed dead flat in the roadway of the avenue. The school had dared to open the water-sheeted and leaf-strewn yard as if the morning were normal. The cold and the wet and alcohol had felled one of the men under the scaffold, plainly enough that a passerby had stopped and phoned for help. After he’d stopped shuddering and regained his feet, he argued bloody-mouthed and dismissive with the EMT crew trying to talk him into the ambulance. A stroller, pushed with blind intensity against the cold, ran right through the middle of the discussion and kept going. Another man who knew him pressed the matter: It’s warm in there, he said. In a compromise, he refused the stretcher and trudged, on sodden running shoes, to the ambulance’s side door. The sidewalks were already being blown dry. The layer of clouds held on a while and then broke, leaving rounded, lustrous ones in a blue sky. The wind over the mouth of the coffee lid sent inaudible vibrations down the cup.

Elegy For The Applebee's Dollarita™

Image: Courtesy Applebee’s

Applebee’s announced at the end of September that throughout the month of October (Neighborhood Appreciation Month), it would offer $1 margaritas, or, Dollaritas™. (New York City locations were exempt from the promotion; margaritas in Times Square still cost $14.) In the company’s news release about the promotion, they stated that the intention behind it was to remind customers of their full name—Applebee’s Neighborhood Grill + Bar. A news item about it was posted in a leftist Facebook—or, Leftbook—offshoot group dedicated to discussing pop culture; the comments with the most likes were “millennial death trap” and “i wonder if i can find daddy at applebees AND get a cheap shitty margarita.” Millennials, it seems, find the idea of Dollaritas™ enticing but also absurd and funny.

Late night confession from an Applebee's bartender. #dollarita

Posted by Bitchy Waiter on Friday, October 6, 2017

On October 6th, a week into the promotion, the Instagram account @bitchywaiter shared a series of now-deleted Snapchat videos by an Applebee’s bartender: the Dollarita™, they reveal, is one part cheap tequila, one part margarita mix, and three parts tap water. People Magazine shared the story with the headline, “Applebee’s Bartender Claims Their $1 Margaritas Are Mostly Water.” Twitter doesn’t seem to care—in the words of user @corey_amber, “‘This Dollarita tastes like shit’ First of all it costs a fucking dollar.”

Celadon, The Unseen Green

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

There was once a color so beautiful that only royalty were allowed to see it. The common folk didn’t know it, but this green was (rather fittingly) one of those “ish” colors with no clear descriptive word. It was an imprecise color, a murky color, found only on special ceramics and created by a thinly applied glaze that transformed iron oxide from ferric to ferrous iron as it fired in the kiln. The green-ish, gray-ish pottery emerged from the fire with a hint of brown and a fine crackle that supposedly reminded those early worshipers of imprecise beauty of jade. Later, this green would go by the name “celadon” (named, supposedly, for a fictional French lothario who wore pale green ribbons) but for centuries in China it was known only as mi se meaning “mysterious color.”

From the ninth century to the late twentieth century, people could only speculate about the true hue of mi se porcelain. They knew it was green, but whether it was an emerald or a sage, they had no idea. Then, in 1987, archeologists discovered a secret chamber of treasures in the ruins of a collapsed temple outside Xi’an. Inside, they found true mi se ceramics. (A brief but important distinction: The word “celadon” is used to describe both the ceramics, which vary in tone, ranging from yellow greens to more gray-greens, and celadon the color, which, thanks to web designers and their exacting taxonomy of colors, is precise, defined, and does not vary. In digital design, it has the hex code #ace1af and is composed of 67.5% red, 88.2% green, and 68.6% blue—or in the CMYK color space, it uses 23.6% cyan, 0% magenta, 22.2% yellow, and 11.8% black. According to the Pantone naming convention, celadon is filed under 13-6108 TPX.)

Mourning jewelry, Obama's scribbles, and a "short snorter"

Lot 1: Bling for Día de Los Muertos

Courtesy of Freeman’s

Jewelry that honors the dead is a creepy/cool tradition that’s been around for ages. Less garish than the sugar skulls associated with the Mexican holiday that begins on October 31, these pieces also feature skulls and skeletons, and sometimes angels, hourglasses, and hair from the dearly departed.

A bone-chilling collection of bereavement bling, once owned by collectors Irvin and Anita Schorsch, is headed to auction in Philadelphia. Among the highlights is a late seventeenth-century gold and enamel “slide” set in seed pearls that portrays, at its center, an angel flanked by two skulls. Refashioned, it would make a perfect engagement ring for “Portlandia’s” Goth couple (and a steal at $1,000-2,000). Perhaps an enameled skeleton brandishing an arrow in one hand and an hourglass in the other, against a braided hairwork backdrop, is more your (spooky) style? That one will cost about the same.

The Clientele, "The Neighbour"

Now that it is finally fall—except for Thursday and Friday, when it is going to be in the 70s again because what are seasons anymore?—you can fully appreciate the autumnal beauty of The Clientele’s Music for the Age of Miracles. So appreciate it already. How many more autumns are you going to get, realistically? Anyway, enjoy.