Coffee

Image: Robin Corps via Flickr

Just like pizza or bagels, coffee is a spectrum. There is no “best bagel” or “best pizza” or “best coffee” because there are so many ways to make them, so many styles and executions. Okay, you think, so there are different categories: Neapolitan pizza, Domino’s (hell yeah), single origin peaberry, Dunkin…Can’t there be a best in each sub-category? What if I just prefer watery cart coffee because it’s comforting? That is somewhat the function of De Gustibus Non Est Disputandum: to each his own—a choice, a preference. You pick yours, I pick mine. We may disagree on the methods of preparation and the quality of the ingredients therein, but ultimately your personal, subjective favorite that you like to label the “best” comes down to an alchemy of factors, including your family history, your net worth, and whether you were breastfed (just kidding!!!!).

Jew-ish

Image: Eugene Peretz via Flickr

I remember my mother’s last Christmas tree. I was eleven, and she was converting to Judaism the following summer: abandoning her native Catholicism to become a fully fledged member of the tribe in time to stand on the bima with me (and my Jewish father) at my Bat Mitzvah.

At that point, it had been a while since we’d bothered to put up a tree in the house—usually, we celebrated Hanukkah at home in Los Angeles and then went to do Christmas with her relatives in Phoenix, evading the question of a so-called Hanukkah bush entirely. We had friends who did that kind of thing, liberal, Reform Jews who didn’t see the harm in helping themselves to what they saw as a charming and basically secular tradition, but my mother felt strongly about it. For her, deciding to become a Jew meant being willing to give up what everyone else does.

Iconoclasm and insularity run deep in Jewish culture. I mean, we call ourselves The Chosen People. The Hebrew word for holiness is kadosh, which comes from the concept of separation. Long before pseudo-spiritual white people co-opted the word to describe folks who share their particular wellness predilections, we were a tribe. We are a minority almost everywhere we live. We have a long history of being persecuted, and we feel safer when the windows are closed and doors are locked, and no one but us is in the room.

New Money

Image: Roy Luck via Flickr

A few years back, I spent a summer in Houston acting like I had money. Then I fell in with some white kids who came from money. I guess you could call it a scene. All gallery openings and coffee bars and stage-dives. We’d flit from club to concert to loft to bed, occasionally stopping to take stock of the time. Or at least I did. Because that shit was brand new to me, very nearly alien, a reality so divorced from mine (black, Caribbean, Baptist, middle class), that I couldn’t help feeling threatened by it, and enticed by it, very nearly always wondering exactly how far it could go.

A few things had to happen for any of that to work. Mostly, I worked the parking lots at NRG Stadium. Made no dollars an hour. I said, Sir, Ma’am, you can’t park that here. Sometimes folks spat at me from their trucks, and my buddy Manny gave them the finger, and I’d up-charge them on their way out. When I wasn’t working, I read novels that were entirely divorced from my life, The Line of Beauty and The Mysteries of Pittsburgh and Gatsby—books where boys, occasionally queer, acquired reams of splendor out of chance and circumstance.

Also, the guy I’d been dating left the States for Busan. We’d found a situation house-sitting for a friend across town. It was our way out of rent. We figured we’d fake playing married, but after a few days of quietly throwing furniture at each other we decided that tapping out was, in the end, the best for us both. So the house I was now sleeping in, alone, was a solid reminder of my social ceiling: no one in my family had ever owned property as nice. Very few people in my family owned property. I was pretty sure I never would. The neighbors cocked their heads at me whenever I mowed the lawn, and I told myself I wouldn’t wave. But usually I did.

Nothing is Fake on the "Antiques Roadshow" Facebook Page

Image: Ninian Reid via Flickr

Watching “Antiques Roadshow” is a background holiday tradition—one of those activities that’s never remarked upon but happens every year at my grandmother’s place. Without those hours spent with PBS, I’m convinced the real traditions would fall apart. At the dinner table, Nana holds forth like the show’s host Mark L. Walberg, or better yet, like executive producer Marsha Bemko. Around the table, we’re alternately experts and students who’ve stumbled upon something someone else can help explain.

Well, that’s bullshit, but still. The holiday season means basic cable, which means “Antiques Roadshow,” which means a few hours spent guessing if heirlooms and flea market gems are fake and, if they aren’t, how their authenticity translates into value, at auction or for insurance purposes. This is the drama of “Antiques Roadshow”: experts litigate authenticity, then turn personal stories and provenance and wear and tear into cash. At the end of each segment there’s the same question, whether it’s asked outright or not. Will they sell it?

Finstagram

Image: Justin Jensen via Flickr

At the end of high school, my brother gave me a (fake) pink plastic Louis Vuitton purse. I carted it around the city that hot, anxious summer of waiting for college, the plastic searing sweaty patches onto my bare skin. The purse, I found out years later, fooled some of my peers: when I met a guy I’d be attending college with, plastic purse in hand, he apparently catalogued me as “one of those Upper East Side princesses.”

To me, the purse was hilariously extra: Barbie pink, plastic, covered in the LV logo? It even had a matching mini purse that clipped onto the side of the whole apparatus—it was too extra to be believable as a serious designer accoutrement. Or so I thought. This attitude didn’t really take into account the all kinds of extra that line designer racks. It also didn’t take into account the power of context: long femme hair and a private school education made me perfect fodder for a certain set of assumptions.

The thing about fakery is it’s so hard to distinguish from reality, in part because it’s not usually unreal, it’s just not what you think it is: fake meat is real food; fake friendships are relationships with tangible effects on our lives; fake news (and “fake news”) move through our screens and communicate something, whatever it’s relationship to “reality.” Even my purse, while not actually Louis Vuitton, was a very real object that I very truly used to carry things around in.

Men Like Him

“He was too much in earnest now to feel any false constraint in speaking his mind.”

In 2018, let us beware of Lawrence Selden, one of the great intellectual bachelors of American literature, the unmarried man whose friendship is the catalyst for the beautiful and unattached Lily Bart’s tragic fall in Edith Wharton’s 1905 The House of Mirth. Let us beware of men like him, the men who feel no social constraint, the authentic, the earnest, the men who imagine themselves as existing outside of society. Let us beware because they are, in fact, fake-ass fakers, and we have to get better at spotting them. Lily Bart is attracted to Lawrence Selden, an unsuitable match, but the true tragedy is that she believes his bullshit, to great cost.

The costs of believing a Donald Trump or a Harvey Weinstein—men with great power who use it in vulgar, obvious, and dangerous ways—are pretty clear. Less clear, though are the effects of the Lawrence Seldens: the bookish men, the leftist men, the “radical” thinkers, the “let us live lives of desire” kind of men. The men whose bachelor libraries we dream of living amidst. The men to whom the costs paid by women trying to survive inside patriarchy are invisible.

Fake Thoughts

Image: sunshinecity via Flickr

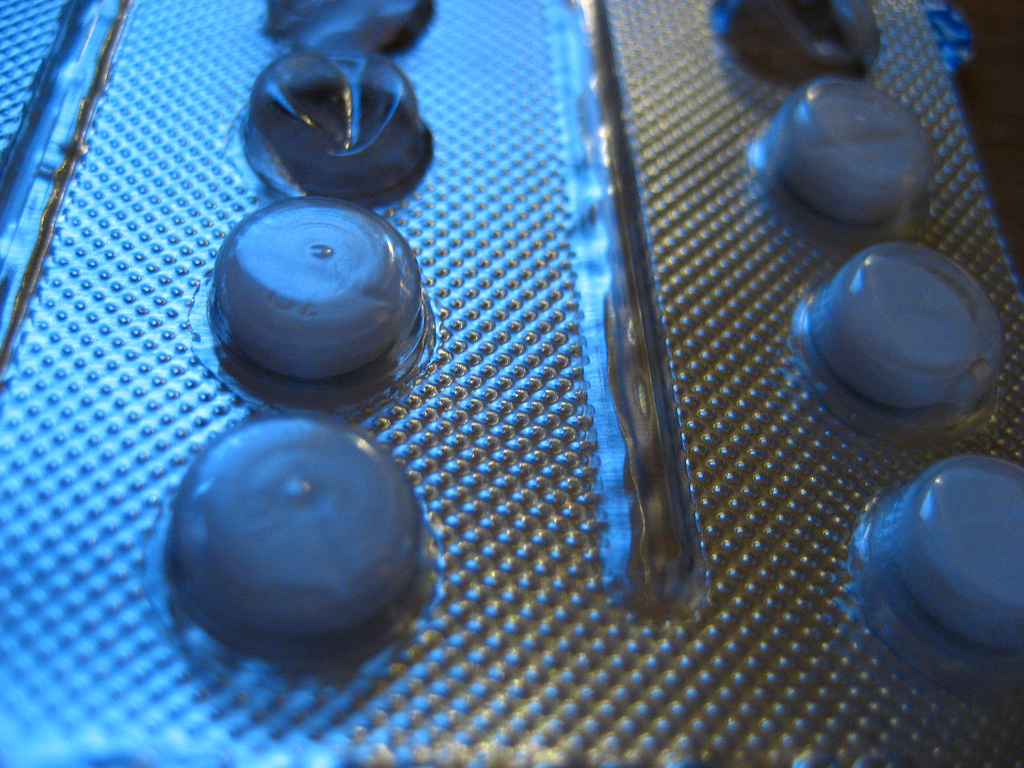

I stopped taking so many pills all at once! This is probably not medically advised and I certainly wouldn’t recommend it but sometimes you just do things, I guess?

The pharmacy claimed my birth control prescription ran out and even though that wasn’t the case, I just didn’t feel like fighting it. And I’m not sexually active and birth control pills probably make me crazy anyway. I mean, I think they do? I started taking them when I was 13 because my period never, ever, ever stopped and I don’t remember that they made me moody or prone to crying jags or anything like that. Because I was a teenager and everything mattered so much but nothing mattered at all. I gave up on them at some point and just dealt with having my period forever.

At some point in my early 20s, I decided that I should probably start taking them again because even though I was using condoms when I had sex, it was probably a good idea to know when my period would start and stop, you know, just in case. Also, there are a whole lot of intimacy issues that come with having a never-ending period, such as never feeling comfortable during any below-the-belt activity. The first couple months were a bit rocky and I got all puffy and I remember crying over the tiniest things like what to eat for lunch. You know, as one does.

Hot Rocks

Evan turned eleven on Groundhog’s Day. Berch, his after-school and summer babysitter, gave him his beat-up copy of the Rolling Stones’ Hot Rocks double LP. Berch, who was sixteen, told Evan that he had lost interest in the Stones on New Year’s Eve, when he heard the Sex Pistols for the first time.

There were black-and-white photos on the inside spread. “That’s Bill,” Berch said, pointing to a man wearing what Evan thought was a ladies’ jacket. “He hasn’t said a word to anyone since the day he joined the band. That’s Brian.” Berch pointed to a blond man with bangs in his eyes. “He was murdered. And that’s a bad shot of Charlie, and those are Mick and Keith.” Berch wagged his finger between two men: one was lighting a cigarette; the other had long hair and a lady’s face. “There too.” He tapped a photo of a guy who had hair that stuck up and out.

“Mick with the hair?” Evan said. He hadn’t heard the name before.

“Keith. Keith.”

“How does he get his hair to do that?”

“What, spike up? You have to have men’s hair to do it. It gets stiff when you’re an adult. Like a head beard.”

Berch brought the photo of Keith a few inches from his own face. Now Evan couldn’t see. He noticed how big the space was between Berch’s nose and top lip. He wondered if this was what made Berch so ugly. Or maybe it was that his mouth was usually open. Berch talked a lot, especially about drugs, women, and music. Even if Evan wasn’t interested, he listened to be polite. His dad said that he had to have a babysitter until he turned twelve, and Evan didn’t want Berch to quit. Two years ago, Berch was the only person to answer the ad that Evan’s dad had put up on telephone poles in the neighborhood. If Berch quit, his dad would have to find someone else. That would be a pain in his dad’s ass. And Evan could get stuck with somebody worse than Berch.

Fake This Marriage

Image: Thomas Leth-Olson via Flickr

May 2011

I visit my parents for the last time and the entire trip I bat away a suspicion that my dad feels left out. I have a new boyfriend, Mark—he’s the purpose of the trip—and I’m so in love with him I sweat with it. My legs and only my legs get sunburned at a Giants game and Mark calls me “watermelon thighs.” My mom insists he sleep in my brother’s room and makes him sing along with her to Elvis Costello. But my dad, even while sitting beside me, always seems to be in the next room.

Two weeks later, he packs a duffle bag with the binder labeled “Stout Family $” and some clean shirts, and leaves. There will be no negotiating the choice. My mom calls me at 5 on a Tuesday, crying, and I take the call in the alley outside my office.

Everything I do in the days that follow, I do by phone. On the first night, I beg my dad to reconsider. He sits in his car at the top of his old driveway, a pizza on the passenger’s seat. I bargain. I demand he hand over evidence against himself for crimes of husband and fatherhood I am certain he’s committed. I insist he tell the truth, as if it’s some static thing I can own and refer to in the coming years. I might as well be storing fog in a jar for later study.

I realize he hadn’t felt left out, because he’d already left. My thighs are still darker than the rest of my legs.

June 2011

My roommate has a friend in town who stays up all night making beans so we can eat them “a la carte” throughout the week she’s here. In the morning, she sees an empty wine bottle and a roll of toilet paper forming a tableau of feminine sadness on the coffee table, and asks me what’s up with that. I tell her about my parents. She nods and puts her hands together as if she’s about to pray. “Mmm” she says, and tells me that there’s a reason for all this: Mars has just entered Taurus. She offers me beans to take to work.

Forging Hitler's Diaries Made Him Famous

Konrad Kujau with one of “his” paintings in 1992. Photo: Wikimedia user Telephil.

Konrad Kujau was born in 1938 in Löbau, Germany, in the midst of a burgeoning NSDAP-mania. His parents were proud Nazis and he, too, would grow up idolizing Adolf Hitler, even after the war was over. As any neighborhood Hannah Arendt will tell you, Nazi idolatry was more common in postwar divided Germany than anyone wanted to admit at the time—the flourishing black market of memorabilia on both sides of the Berlin Wall was proof positive just on its own. And that is how, in the late 1970s, Konrad Kujau—by this time an experienced small-time grifter and semi-talented handwriting imitator who was already selling fake Nazi memorabilia in his Stuttgart shop—decided to write a sloppy, poorly researched fake diary of the Führer and see who would be interested in it.

He taught himself the old Gothic script that Hitler favored, and then he used watered-down ink on modern paper that he stained with tea and whacked against furniture to age. He bound the whole mess up with a Nazi-era ribbon and a red wax seal, and as a final detail he had Hitler’s initials stamped on the cover in gold. Well, he tried to, at least. In addition to teaching himself Gothic script, he’d also taught himself to read Fraktur type—poorly. Apparently when he was buying the Hong Kong-made Fraktur printer’s type, he mistook a Fraktur “F” for an “A.”