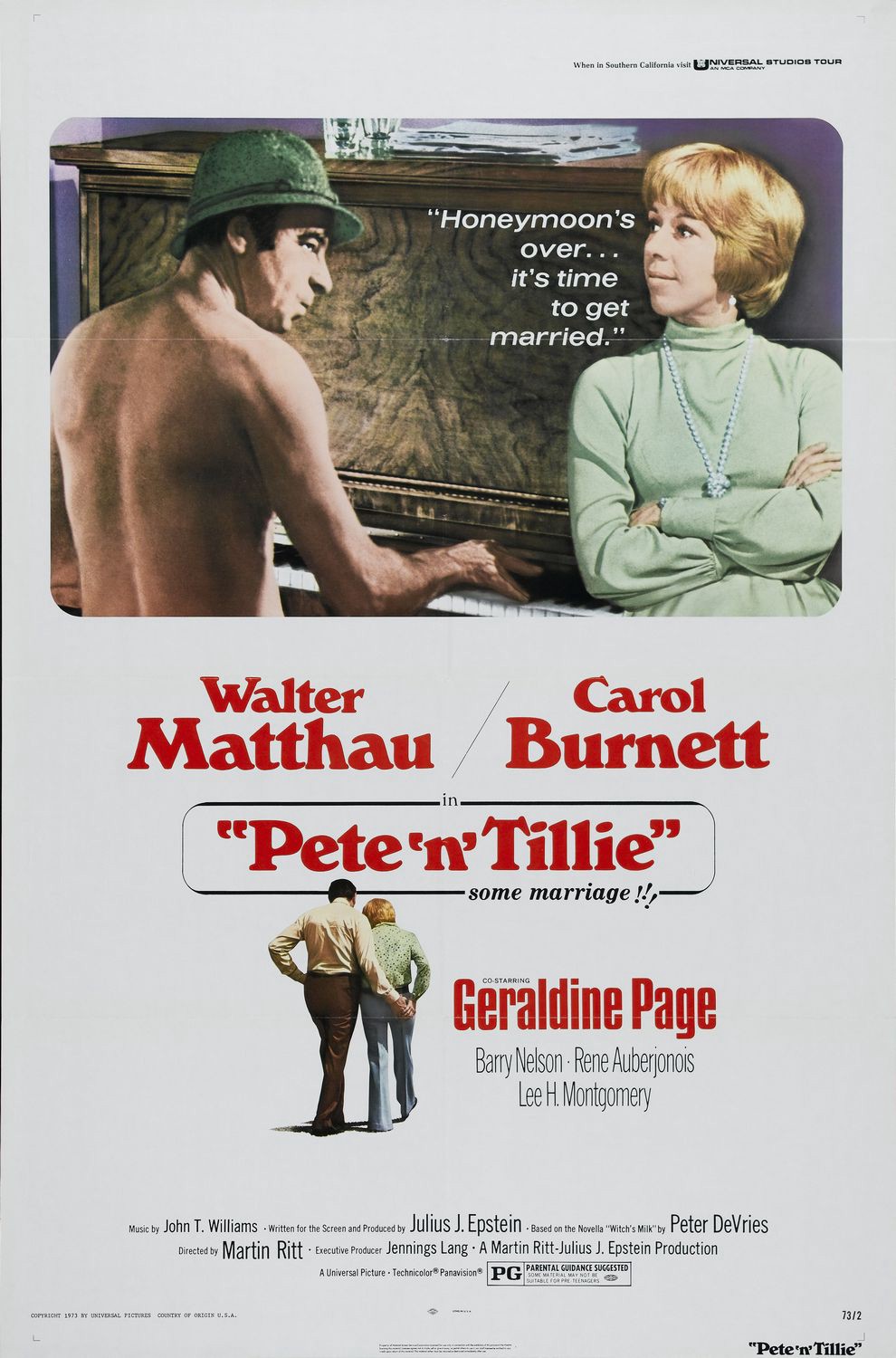

'Pete 'n' Tillie' (1972)

Carol Burnett and Walter Matthau as disappointed spouses.

No one alive has a higher tolerance for Doris Day movies than I do, but I detested 1958’s The Tunnel of Love. In it, Richard Widmark — normally commanding and vigorous but, here, twitchy and miscast — contemplates cheating on his wife, played by Doris Day. Did you hear me? I said Doris Day.

The Tunnel of Love was based on the Broadway hit mined from a 1954 novel by Peter De Vries. In his 2004 New Yorker profile of De Vries, Jeffrey Frank laments that the author’s novels are now out of print and largely forgotten. It’s fair to wonder why, as the work of De Vries — who died in 1993 — earned enough acclaim during his lifetime to launch four Hollywood movies. All four films center on men of sketchy desirability who are either reliably bedded by attractive women or consider being unfaithful to what seem to be cracking good wives.

I have nothing nice to say about three of those movies: besides the smarmy The Tunnel of Love, there’s 1983’s smarmier Reuben, Reuben and 1970’s smarmy-sounding How Do I Love Thee? (it’s not on DVD or currently streamable so I haven’t seen it). But the fourth film, 1972’s Pete ’n’ Tillie, based on De Vries’s 1968 novella Witch’s Milk and directed by Martin Ritt, gets something exactly right about an enduring marriage’s disappointments: they are persistent but neutralized by time.

The schlubby Pete (Walter Matthau) and the tamped-down Tillie (Carol Burnett, brilliantly cast against type) meet at a party at the Bay Area home of Tillie’s matchmaking best friend, Gertrude, who is on the knifepoint between studied good grace and natural-born vulgarity as only Geraldine Page could have played it. Tillie is a secretary; Pete is in “motivational research,” which means that he’s all about the sell and always has a line ready. In front of Gertrude’s guests, who include her priest, Pete tells her, “I didn’t know you were asking Father Keating. I demand equal time for my rabbi.” When Gertrude asks why he identifies as a Jew when he’s three-quarters Lutheran, Pete says, “Because I’m a social climber.”

Tillie, a teetotaler, doesn’t laugh at his jokes. To his not at all impertinent question “Where were you born?” Tillie answers “Why?” Pete admires both her resolve and her quick wit: “You have possibilities,” he tells her after she makes a decent pun. With her perpetually crossed arms (on which Pete remarks), Tillie has the bearing of someone who has been wounded, although there’s no backstory here beyond a reference to a father who bailed early. Presumably being a thirty-three-year-old single woman in the 1970s is sufficient reason to live life on the defensive.

It’s only after they start sleeping together that Tillie feels she can smile around Pete, whose entertainment value, as when he plays his piano starkers, she can’t deny. But after one of their trysts, she finds a woman’s hairpins on his bedroom floor. She shows them to him. They both pretend the pins belong to his cleaning lady.

The characters’ rat-a-tat exchanges are faultless; Burnett and Matthau, here in their first screen collaboration, are like a low-energy version of Pete’s beloved Abbott and Costello. But after they’ve been dating awhile, it’s Tillie who has the best line: “The honeymoon’s over. It’s time to get married.” Tillie and Pete move to the suburbs, where she uncrosses her arms to embrace full-time motherhood.

The honeymoon is really over the day Tillie goes to Pete’s office to surprise him. A receptionist tells her that he’s not on the premises, so Tillie waits. Eventually she spots Pete in a hallway talking to an attractive younger woman whose hair he fiddles with. For a fleeting, uncharacteristic moment, Tillie becomes a Carol Burnett character: she hides in the office john. That night she confronts Pete; he says the woman is a new employee and scrambles for a joke. This won’t be Pete’s only other woman. If Tillie considers leaving him, one impediment is the effect that this would have on their son. As the movie makes carousingly clear, Pete is the all-laughs dad that one would expect Walter Matthau to be.

I don’t know if there’s another comedy-drama that better accommodates the sort of horror that life occasionally drops anvil-like on the least suspecting and even less deserving. Following just such a tragedy, Tillie and Pete retreat to separate corners of their marriage. One night, Pete, sozzled, points out that they haven’t had sex in a year. Tillie has no objection when he tells her that he will once again be working late, so to speak, the following evening. He takes an apartment in town.

Adrift, Tillie throws herself into charity work with Gertrude. At lunch one afternoon, she tells the elegantly oily Jimmy Twitchell (René Auberjonois), a gay friend in Tillie and Gertrude’s circle, that she is going to the police station the following day to formally register a lottery that the charity is holding. Jimmy insists that Tillie take Gertrude with her because the police will, as a matter of course, ask Gertrude her name, address, and age, the last of which he has long been desperate to learn. “I can’t do that to my best friend,” Tillie says. “But darling,” Jimmy says, “what are best friends for?”

At the station, Gertrude responds to the question of her age with a succession of nonsense syllables and then makes a quick getaway: a dead faint, probably faked. Once they’re outside, Gertrude tells Tillie, “You did this deliberately. You planned it!” She swings her pocketbook like a cudgel; Tillie, who has much more to be mad about, swings hers harder. She threads a running garden hose up Gertrude’s dress; Gertrude puts a trash barrel over Tillie. This sounds like comic relief — the clowning promised by Burnett’s name on the movie theater marquee — but the scene is shot with a marvelous, almost wordless brutality. In another movie, their blows would have concluded with spluttering laughter. Here, once Tillie has pulled off Gertrude’s wig, the scene, and for all we know the friendship, ends. So much for the narrative cliché that catharsis breeds clarity: Tillie goes from the catfight to a mental health facility. But she hasn’t seen the last of Pete.

Pete ’n’ Tillie was well received at the time of its release, earning deserved Oscar nominations for supporting actress Page and screenwriter Julius J. Epstein, but I’m aware of the film only because Burnett mentions it in her 2010 memoir, This Time Together. Part of what may have hurt Pete ’n’ Tillie’s chances at enduring recognition is that it’s about something that not even Pete could market easily: two middle-aged lovers who don’t look like movie stars.

It’s also possible that the film disappeared for the same reason that I suspect De Vries’s work did: having heard the gong of the women’s movement and other cultural wake-up calls, the public may have lost at least some of its taste for, or maybe patience with, stories about the middle-aged American male’s sense of sexual entitlement. At least I hope it did. There’s a clue that the filmmakers felt less indulgent of Pete than De Vries did: they invented a scene in which Gertrude’s husband propositions Tillie. (She turns him down.) Although Pete cheats on her, Tillie’s desirability is not in question.

Pete ’n’ Tillie’s ending is both the right one and not the one you wanted. If the film had been made in Doris Day’s time, it would have concluded with dueling Technicolor apologies and a glossy smooch. If it had been made today, I can picture a one-way spray of expletives followed by an applause line and flag-planting in the land of female self-sufficiency. But Pete ’n’ Tillie came out between fifties romanticism and the socially aware idealism of right now. Splitting the difference between Pillow Talk and Thelma and Louise, Pete ’n’ Tillie plants its flag in 1970s realism’s heart. Tillie may not end up uncomplicatedly committed to her fate, like the protagonists in those two movies, but someone of her generation and type — probably not you, and surely not me — might consider herself no worse off than Doris Day, who, after all, got stuck with a dick like Richard Widmark now and then.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor. She writes occasional Best Forgotten columns for The Awl.