All The Drunk Dudes: The Parodic Manliness Of The Alcoholic Writer

by David Burr Gerrard

It’s difficult not to romanticize a link between writing and drinking. Wisdom hurts, so the more wisdom a writer has, the harder the writer will try to drown it with alcohol. Or maybe it isn’t wisdom that needs to be drowned; it’s the inner editor. Or maybe the great passion that leads to great writing also leads to great drinking. Or maybe… anyway, there must be some connection, so can we please put down our horrible manuscripts and pour ourselves some bourbon already?

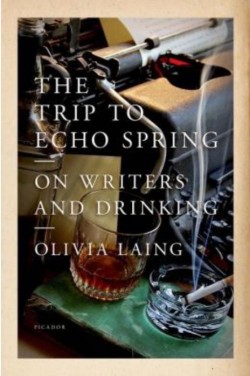

There is no romanticizing in The Trip to Echo Spring, British journalist Olivia Laing’s new group biography of six alcoholic writers — Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, John Berryman, and Raymond Carver. There is also no demonizing, even when demonizing might be warranted. Taking the form of a travelogue and incorporating Laing’s own family history, The Trip to Echo Spring takes aim at the evasions and delusions of these men (and they are all men), but does so in a way that somehow increases our understanding of and admiration for their work.

Laing and I discussed her book over whiskey at the capital of New York literary dissolution, the White Horse Tavern, where Dylan Thomas… actually, we met for coffee at a Pain Quotidien. (As it happened, no waiter ever came, so we conducted the interview without the aid or influence of any beverage at all.)

The Trip to Echo Spring is available wherever one most likes to purchase books!

• Amazon

David Burr Gerrard: So let’s start with an obvious question. Why’d you write the book?

Olivia Laing: The first impetus for it came a really long time ago. I was seventeen, I’d grown up in an alcoholic family, and we were studying Cat on a Hot Tin Roof at school. Pretty much as soon as I read it, I felt that this was explaining some things about a situation I’ve experienced. I guess that stayed there as an underwater interest. Over the years, I realized that Tennessee Williams was an alcoholic, and these other writers I loved were also alcoholics. It became clear that there was a book to write.

And why these writers?

It had to be writers that I loved. I think there’s a real tendency in dealing with this kind of material to be sort of trashy about it or sleazy or to take pleasure in seeing them throwing up. I really didn’t want to do that. You can get a very spiteful tone if there are people whose writing you don’t appreciate. The other thing is that I wanted some sort of commonality. They didn’t have to be friends, necessarily, but they needed to have points of encounter.

One experience of reading the book is wondering why this writer and not that writer. Why Berryman and not Robert Lowell? Why not William Faulkner? That just brings into focus just how many alcoholic writers there are.

I give that list in the beginning. You could make a similar but differently contoured book about any six writers. You could do it about six women. There are so many ways you could do it.

So why did you choose six men?

My childhood. My mum’s a lesbian, and her partner was the one who was drinking. It just felt too close to the bone. Too personal, somehow. It would make a terrific book, and it’s the question I always get asked if I give a talk or a reading. What about all of these women? Patricia Highsmith would have been fascinating. But I almost physically couldn’t do it.

It’s interesting that you mention Patricia Highsmith, because she’s not as canonical as the writers in your book. There seems to be a lot of male privilege here. These guys act horribly, and yet we either pardon them or treat their horrible behavior as part of their genius.

Absolutely. And it’s a very different story with women. Like with Jean Rhys, who I think is really interesting. To her contemporaries and in retrospect, that looks like a really sad life in a way that I don’t think we think of Hemingway’s life as a sad life. “Hey, he was a big guy, he had fun! Maybe he shot himself in the head, but…” There’s sort of a bro-ishness about it, whereas women don’t get that. It would be a really interesting thing to look at, but it wasn’t my subject. Also, my previous book [To The River] was about Virginia Woolf, so I felt like I had already done something about women writers.

That hasn’t been published in the US, has it?

No. It’s a very English book.

There is a lot in this book about sexuality. Obviously there’s John Cheever and Tennessee Williams, but Hemingway’s and Fitzgerald’s drinking seems also to have been connected to proving masculinity.

I found that really fascinating. And I don’t think you want to do something as crude as say that they were in love with each other, but there were definitely tensions and ambiguities in their relationship. And sexuality is so much a part of Cheever’s alcoholism — that he just can’t confess to himself who he is and what he desires. That sense of having to constantly bury something is really a driving force in his drinking. But then, Tennessee Williams was out and proud, incredibly courageous, and it didn’t mean that he wasn’t an alcoholic. It’s not like it saved him.

In the UK, The Trip to Echo Spring’s subtitle is Why Writers Drink. In the US, it’s On Writers and Drinking. Why the more modest subtitle here?

It was a mistake, that subtitle. It was not a good idea. It’s not answering that, really. It’s why these six writers drink. I don’t think the “Why” question is answerable. I’m a lot more comfortable with this one being more open-ended. I think it better represents what kind of book it is.

Raymond Carver is the last writer that you discuss. He has in some ways the happiest of endings, but even he was abominable to his first wife in particular.

Horrific. I didn’t actually know so much about that until I started doing the research. I kind of wanted the book to end with Carver being a great guy. “What a mensch!” And he wasn’t. There were things in his recovery that were really quite disturbing and distressing. I think he’s so wonderful that I really wanted him to heal his relationship with his children and apologize and take responsibility, and those things didn’t really happen.

I think that’s much more genuine. Most people don’t become a saint afterwards. But it was quite uncomfortable to confront. I felt it myself: “Oh, I’m disappointed by you.” But at the same time, he stopped drinking. He totally did do that. And he did create this sort of pretty wonderful second life for himself. He just didn’t extend it to every area of his life, as far as one can tell from the record.

Do you think that the fact that these men were alcoholics is part of why they’re canonized?

That is a very interesting question. I wonder, because it’s such a part of the myth of the great American twentieth-century writer. A kind of manliness, almost a parodic manliness. Hemingway with his guns. Being able to drink hard. That sort of toughness. I wonder if the lifestyle has to go with it.

More recently, we’ve seen it with David Foster Wallace.

People do like those stories, and they do romanticize them, they do make them seem very glamorous. And, yes, much more for men than for women. It’s a lot more attractive. Appears to be a lot more attractive. Which is ridiculous, really, when you think about it.

Looking at it from a devil’s advocate perspective, it does seem that a lot of really great writers were alcoholics. What would you say to somebody who said: there must be something there, some kind of connection, it must be fueling the writing or taking the edge off in some helpful way?

One of the things I came to think is that, certainly in these six, the desire to write and the need to drink came from a similar place. They came from these fractured childhoods. They had desires as very young boys to escape, to fabricate wonderful narratives that would take them away. They were often very sexually awkward, and that’s the way that they could make contact with their peers. So that seemed to be part of it. And there is definitely a thing about social anxiety and shyness. That’s something drinking is fantastic for: it makes you feel more confident. Which is great if you’re a little bit withdrawn and you want to be more worldly. And the last thing is stress. Somebody like Hemingway, who is under tremendous amounts of stress, uses it to self-medicate. It’s a wonderful strategy for a year, five years. When you’re doing it for decades, it comes at such a cost. The effect it has on the brain, the effect it has on the psyche. It obliterates everything that’s important in one’s life, so writing is almost automatically going to become secondary.

Both of your books have travel narratives. How did you come upon this particular genre?

I stumbled upon it, literally. It seems like a really good way of telling the kinds of stories that I’m interested in, because when one is walking, one is automatically digressing, and following ideas, and then returning to a path. If you want to write a book that involves biography and elements of science and elements of history, it’s a really good way of containing those things. The other thing is that lives are lived in places, and I’m fascinated by what remains in a place, by what doesn’t remain. It seems like a really good way of thinking about history in a way that conventional biography can’t always address. Those absences.

And the title comes from Cat On a Hot Tin Roof, this “trip to Echo Spring.”

Actually when you ask where the book comes from, it comes from that phrase. I just find it so fascinating. Brick says he’s going to make a short trip to Echo Spring, and he kind of means he’s going to walk to the liquor cabinet and drink some bourbon, but he also means all these other things. He’s in this claustrophobic house; he can’t confess his sexuality. The trip to Echo Spring is an exit to another place, and that place is what I wanted to know about, really.

Brick also talks about “the click,” where he feels at peace after drinking. One of Berryman’s most famous poems begins “Life, friends, is boring.” There’s that sense of escape.

Berryman did a Paris Review interview just before he died. He says I want as much pain piled on me as possible, I want to be crucified, because that’s what makes for good art. So I think there are these two divergent tendencies. One of them is: “bring it on, let me suffer so I can write about it,” and the other is a small boy saying “ow, this hurts, I want out, I can’t do it.” Totally contradictory impulses, coexisting in the same person. It’s incredibly potent.

You’ve mentioned bringing in science. There’s been a lot of recent popular writing that brings in science and tells a story about some genius, and then you have a study, and then you have a lesson. That’s not the sort of writing you’re trying to do.

Yeah, I’m not a fan of that kind of writing. My background is in science, but that sort of pat approach is very anti-art, I think.

So what drew you to science and then what drew you back to literature?

I guess it started with literature and then I got away from it. I don’t know, really. I was studying medicine, and there was a similarity between medicine and literature that was about narrative, the patient’s narrative. It was a kind of textual analysis, and at that point I’d done enough literature studies that applying that to people was very interesting. Janet Malcolm says that thing about how everything’s on the surface, and everything’s given away by small gestures and small interactions. I think that’s very good training for a writer. Forget MFAs. Medicine is a good discipline.

There are a lot of great writers who are doctors.

There are, aren’t there? It makes you a very close watcher. It makes you look for difference and for things that don’t quite fit. You’re looking at how things work, which is what you’re always doing as a writer.

It’s very interesting that alcoholism is connected to masculinity, since alcoholism makes sexual performance more difficult.

It’s a different kind of masculinity, isn’t it? It’s the performance of masculinity, a butch fantasy. I don’t think it’s about women or sex at all, I think it’s about impressing other men. This sort of display. I’m particularly thinking of Hemingway, with the guns. I don’t think that’s about pulling the chicks. I think it’s about power. And I wonder if the drinking is also about power. For a drinker like him, it’s a way of saying: “I can take more of this poison than you guys can.”

Writers tend to be introverts. Is a lot of writerly drinking just about longing for connection and killing inhibitions?

Maybe. And whatever kind of person you are, writing is a tough life. You are totally on your own. You have to be on your own to write. Lots of my friends are film directors or in theater. Their creative life is so different, in that they’re constantly collaborating and working around other people. Writing seems to me one of the most extreme art forms, in that you have to spend hours and hours each day by yourself with this world you’ve created. Until you get to the editor stage, which is a long way down the line of the book, no one really cares what you’re doing, no one really cares about this thing you’ve managed to do with a sentence or a paragraph. However damaged or introverted you are, or however totally healthy, there’s still a need to change the channel. “Now I need to go to the bar and be around people and noise.” This is a punishing life.

You’re not a teetotaler, correct?

I drink. I drink like British people drink: moderately. I know that this would not be an addiction for me. That’s where the genetic side comes in. There have been points where I’ve maybe drank a bit more than others, but it’s never felt like it was becoming habitual. Whereas I’ve had friends who have been alcoholics. Their relationship to alcohol was totally different. That’s something I wanted to contend with as well. These guys weren’t heavy drinkers: they were alcoholics. That’s a very specific thing, an entire personality structure. Whoever you were before, it takes you over. So you can watch them becoming these almost vampiric figures. I don’t want to overdramatize it, but it’s possible to see that alcoholic personality emerging in all of them. Like Berryman phoning up his students in the middle of the night and threatening to kill them. He had been such a decent, ethical teacher, he took teaching so seriously; that’s not the person he was, yet that’s the person he became.

A lot of people say that writers today are too cautious, their lives are too calm. What do you think about that?

It is said, isn’t it? A lot of what we haven’t said about drinking is that it’s the twentieth-century story. Everyone was drinking like that; it was a much more lubricated society. That’s really wound down. Even when I began working at newspapers, people drank at lunchtime. That changed very quickly. And then it was very much frowned upon. So that’s the direction our culture’s gone in. I don’t know that it’s necessarily problematic.

Do you feel that contemporary writing is safer than the writing that you’re writing about?

In terms of the process or in terms of the product?

The product.

No, I don’t. I’m never certain about the MFA culture — I kind of think that writers should have lives that are something other than writing. I think that writers should have life experience. But I don’t think that writing has become more conventional or conservative. There are such exciting things being written all the time.

But you would say: Go to med school rather than the bar.

(Laughs) Possibly. That might be my advice. Seems a bit sadistic, though.

David Burr Gerrard’s debut novel, Short Century, will be released in March. Photo of Fitzgerald’s grave by Melanie Dawn Harter.