How Much More Do Baseball Players Make Today?

In honor of Opening Day on Sunday, the first of two essays today on the history of the game.

It’s almost impossible to think of baseball without thinking of money. There’s no better example than headline-grabbing Alex Rodriguez, third baseman for the New York Yankees. In 2000, he signed an alarming ten-year deal with the Texas Rangers for $252 million (which the Yankees traded for in 2004). This is the deal he opted out of during (like, in the middle of) Game Four of the 2007 World Series, only to sign another ten-year deal with the Yankees, this time for $275 million. Now, with Opening Day days away, the oft-injured (and not-oft-loved) Rodriguez stands to make $28 million for the 2013 season.

Not only is baseball the dream-catcher of American nostalgia and the obsession of math nerds everywhere (why, would we even have a Nate Silver without baseball?), it’s the first American sport to become a professional sport, a big-time, nationwide business concern. So as we have done in the past with the Super Bowl and movie stars), let’s engage in the other American Pastime, talking about how much money other people make.

A SHORT HISTORY OF LONG BALL

Baseball is an old game, older than the Civil War, with hazy origins dating back in time and over to England. Maybe you’ve also heard that old saw about baseball being the brainchild of Union general Abner Doubleday? Actually, that’s a pretty interesting story.

As the 19th century was giving way to the 20th, baseball was already well established. A debate arose: was baseball a purely American invention, or was it a permutation of one of the other stick-and-ball games from across the globe (or, heaven forfend, from England)? A commission was formed in 1905, comprised of former baseball officials, ex-presidents of the National League, former players, that sort of thing. Known as the Mills Commission (after Abraham Mills, one of those former presidents), they began their investigation, looking back more than 50 years for an answer as to the origin of baseball.

In the prosecution of this investigation, they issued public requests for anyone out there who might have some personal recollection pertinent to the issue. An old feller from Denver, Abner Graves, responded, claiming to remember Abner Doubleday scratching a diamond into a field and writing down some rules in Cooperstown, NY, in 1839. Either Graves’ account was so convincing or the Commission was so desperate for an answer that this version was accepted without the Commission corresponding with Graves (who was five years old in 1839) in any way. In 1907, the Mills Commission issued their final report — Abner Doubleday invented baseball, case closed.

In all likelihood, Abner Doubleday had nothing to do with inventing baseball. At the time he was supposed to have done, he was actually at West Point. (Later, once he was a general, he’d fire the first return cannon shot at Fort Sumter and command at Gettysburg.) Of course, West Point is not far from Cooperstown, where Doubleday was said to have drawn a diamond and devised rules in 1839, so it could have happened, but Doubleday never said anything about it, and he is not in the Baseball Hall of Fame. So, Doubleday: Badass? Well, his side didn’t exactly lose the Civil War. Father of baseball? Probably not.

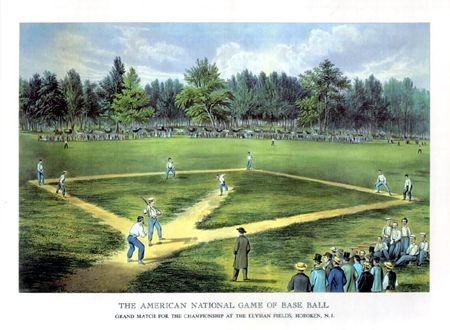

None of this is to imply that baseball was not actually created at some point. The first organized game was at the lyrically named Elysian Fields in 1846, in Hoboken, NJ, of all places. This was not the baseball that you’ll be listening to on the radio in a few days time. From the beginning and for the next 25 years or so, baseball, having been born, grew: young men would band together and form clubs, and then these clubs would play each other. Remember that at the time, the concept of a team sport in America was not as ubiquitous as it is now. Before admission was ever charged for a game (originally presented as exhibitions), some of the clubs would even keep themselves afloat by charging dues from the players. Baseball as it started was mostly an East Coast phenomenon that bled into the Midwest, because that was the extent of the United States at the time. (Baseball: older than the state of California, admitted 1850.)

An 1866 Currier & Ives lithograph of a game at Elysian Fields. (Via.)

At this time, the game was that, a game. Players were amateurs in the modern sense, as no one got paid. Oh, some players did get paid — what we now consider “ringers” were sometimes paid under the table, and there were rumors of game-fixing, as an inevitable result of friendly wagers placed on the outcomes of the games — but baseball was clearly an avocation. This changed in 1869, in Ohio, as the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first officially professional baseball club. Two years later, the National Association of Base Ball Players formed, the first professional league (of any sport, in America). It didn’t last long, but the game was no longer a game. It was a sport, a vocation, and, most importantly, a business.

And now we begin to get a baseball that would be recognizable today. The National League was formed in 1876, with the original teams: the Boston Red Stockings, the Chicago White Stockings, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, the Hartford Dark Blues, the Louisville Grays, the New York Mutuals, the Philadelphia Athletics and the St. Louis Brown Stockings (proving that naming things is hard). The National League did not instantly dominate the baseball landscape, filled with competing, short-lived leagues, minor leagues and semi-professional organizations, but it was stable, and it is the entity that would eventually become Major League Baseball. The National League was still standing by the turn of the century, expanded and sometimes taking teams from failed leagues.

Meanwhile, half the country away, a Midwest minor league that called itself the Western League, founded in 1885, decided in 1891 to rename itself after the name of a notable competitor of the National League, the American League. The American League mounted a notable effort against the National League, undercutting each other for cities, and by the turn of the century the two decided that merging made more sense than being at each others’ throats. (If you can’t beat ’em, join ‘em.)

They signed a National Agreement in 1903, recognizing each other as a truly Major League, and agreed that the champion of each league would face each other in the World Series.

At that point, a new industry of professional athletics left its adolescence, and since then, millions of hours and words have been spent, passing time in that most American of ways.

IN THE DAYS WHEN THE BASEBALL CARDS CAME WITH SMOKES

It’s easy to think that the rapaciousness of baseball is a side effect of a modern world, that there was once a pure state of The Love Of The Game, an eden where players were happy just to have that happy job, and owners would descend into the bleachers once a game and dole out hot dogs.

That is not so much the case.

Even in the pre-history of baseball, back when the National League was fending off competitors, the actual competition between the leagues would be more apt as an HBO series than a measured documentary. Turfs were protected zealously, and attempts to undermine rivals were cutthroat. Half-price admissions were par for the course, and one of the easily exploited rules of the National League back in the day is that they did not play games on Sundays and they did not serve beer. So please come see the newly-arrived competing team (named after footwear, or a hat) on Sunday at two, and have some suds while you’re here!

Even the media sponsorship, the acceptance of filthy lucre for the right to broadcast/telecast/stream/beam-directly-into-your-head the copyrighted material, the property of Major League Baseball that comprises each game, that’s also not such a new thing. In 1897, the major leagues sold the right to telegraph the play-by-play of games to saloons, for $500 worth of telegrams for each team. By 1913, each team was paid $17,000 per year for such telegraph rights. 1913 is coincidentally the earliest year indexed by the BLS Inflation Calculator, so that seventeen large would be $398,699 in 2013 dollars.

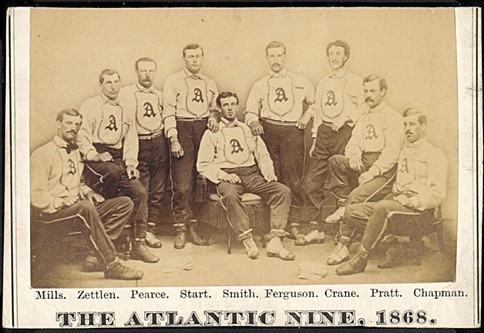

Even baseball cards, the totems of many a kid’s childhood, were emblematic of commerce well before they became the scourge of the collectibles shows of dying shopping malls everywhere (or fuel for the trash fire). Long before they were licensed inserts given away with some quantity of unchewable chewing gum, they were trade cards, a 19th-century precursor to advertising as we know it. A shop owner would print up a stack of cardboard cards, detailing the location and hours of the shop, and include an illustration or a photograph of a local team or player, for maximum eye-catchability. One of the first recorded appearances of a baseball club on a trade card is 1868, from baseball equipment manufacturer Peck and Snyder, featuring the Brooklyn Atlantics. By the end of the 1890s, baseball cards were predominantly premiums, given away with packs of cigarettes, giving way to the candies and “gum” later in the century.

An early Peck & Snyder baseball card, from 1868: the Brooklyn Atlantics.

And do note that it’s not just the League that benefits from licensing income from baseball cards. The League does keep fees related to logos and teams, and the player’s union licenses the individual likenesses of the players. It’s a business, like any other.

SO HOW MUCH MONEY COULD YOU MAKE PLAYING BASEBALL?

So let’s get to the actual money, already. For the last nine years of his career, from 1908 to 1917, Honus Wagner made $10,000 a year from the Pittsburgh Pirates! At the height of his success in 1930, Babe Ruth gets a raise from the Yankees to $80,000 a year! Hank Greenberg was the first $100,000 player, when the Pirates traded for him in 1947! We know these things, but information concerning overall trends back then in the Dead Ball Era, or even more recently, say during the first Yankees dynasty, is not so easy to come by. Baseball teams were privately held, as was the League, and perhaps we just didn’t care about exposing the inner workings back then as much as we do now.

But we do have reliable information going back nearly 50 years, so below are the average baseball player salaries, league-wide, by year.

(There is more than one source for average salary information, and if you go looking for one, you may well find that they do not all agree. Some account for signing bonuses and traded players in different ways. But the discrepancies weren’t egregious, and, face it: we’re doing this just for fun. And the most useful resource, one frequently cited by other sources, is Michael Haupert’s “The Economic History of Major League Baseball.”)

The averages run:

1964: $14,863 ($111,312)

1965: $14,341 ($105,698)

1966: $17,644 ($126,430)

1967: $19,000 ($132,070)

1968: $20,632 ($137,646)

1969: $24,909 ($157,909)

1970: $29,303 ($175,339)

1971: $31,543 ($180,821)

1972: $34,092 ($189,354)

1973: $36,566 ($191,202)

1974: $40,839 ($192,321)

1975: $44,676 ($192,793)

1976: $52,300 ($213,397)

1977: $74,000 ($283,503)

1978: $97,800 ($348,249)

1979: $121,900 ($389,821)

1980: $146,500 ($412,771)

1981: $196,500 ($501,877)

1982: $245,000 ($589,440)

1983: $289,000 ($673,654)

1984: $325,900 ($728,228)

1985: $368,998 ($796,178)

1986: $410,517 ($869,599)

1987: $402,579 ($822,757)

1988: $430,688 ($845,234)

1989: $489,539 ($916,567)

1990: $589,483 ($1,047,115)

1991: $845,383 ($1,441,037)

1992: $1,012,424 ($1,675,342)

1993: $1,062,780 ($1,707,553)

1994: $1,154,486 ($1,808,586)

1995: $1,094,440 ($1,667,268)

1996: $1,101,455 ($1,629,830)

1997: $1,314,420 ($1,901,332)

1998: $1,378,506 ($1,963,449)

1999: $1,726,282 ($2,405,666)

2000: $1,987,543 ($2,679,674)

2001: $2,343,710 ($3,072,225)

2002: $2,385,903 ($3,079,075)

2003: $2,555,476 ($3,224,427)

2004: $2,486,609 ($3,056,146)

2005: $2,632,655 ($3,129,611)

2006: $2,866,544 ($3,301,161)

2007: $2,944,556 ($3,297,093)

2008: $3,154,845 ($3,401,939)

2009: $3,240,206 ($3,449,874)

2010: $3,297,828 ($3,511,224)

2011: $3,305,393 ($3,411,591)

2012: $3,440,000 ($3,478,536)

As you can see, player salaries, starting in the mid-70s, began to climb steadily, shooting through any number of roofs — in 48 years, the average salaries have increased by 3,125%. The average salary for a player in this period was never exactly an insult, always at least six figures, but by 1990 entering millionaire territory.

It seems that baseball has been very very good to them. How did this happen? The short answer is, “Free agency happened.” Know that and consider yourself armed with knowledge. But naturally it’s more complex than that, more like, “The antitrust exemption bumped into arbitration, and then free agency happened.”

“I AM DEAD SET AGAINST FREE AGENCY. IT CAN RUIN BASEBALL.”

Early in the history of baseball, owners of teams encountered a labor problem: if they had a player (say the NY Gothams catcher Buck Ewing, the first player to hit ten home runs in one season, in 1883) that was performing tremendously, what would prevent a competing team from enticing that player to break his contract and sign with the other team for more money. The solution: the teams agreed to a “Reserve Clause,” whereby a team would “reserve” certain players (and later, entire teams), and all the other teams agreed that the reserved players were inviolate. The shorter word for this is “collusion,” of course, but in the formalization of first the National League and then the Major Leagues, it was a condition of joining for prospective member teams.

And we should be careful in typing “collusion,” because it’s a word that keeps MLB up at night. MLB is the proud owner of an antitrust exemption, which gives them the right to violate the Sherman Act, which prohibits monopolies. This exemption is not a medal or a piece of paper; in fact, you could argue that it’s not so much an exemption as it is an general agreement to not pursue Sherman Act charges against MLB. It was created in a 1922 Supreme Court decision, The Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v the National League, which upheld an earlier decision that baseball was not the sort of interstate commerce that antitrust laws were meant to govern.

Enter the unions. There were a number of attempts to form collective bargaining organization for players over the years (the first, in 1885: The National Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players), but none of them stuck. The owners held all the power — hiring and firing, working conditions, arbitrary salary increases/decreases — and the players failed to organize, as the life of a successful baseball player was still pretty sweet, especially in comparison to companies with similar overarching power. The current union, the Major League Baseball Players Association was formed in 1954, and managed to remain in existence until 1966, when it hired former steelworker labor negotiator Marvin Miller.

Miller (who really should be in the Hall, no?) immediately began to get results. The first collective bargaining agreement negotiated by Miller in 1969 raised the minimum salary to $10,000 from $6,000 (more on that later). But his ultimate goal was the Reserve Clause. The aspect of the Reserve Clause that prevented players from having any bargaining power was that each player contract, which must be signed by each player prior to Opening Day, was a one-year contract with a team option for an additional year. That gave each team a perpetually renewable option on the player, and since other teams agreed not to poach players, the player had no recourse other than to say yes. “Play me or trade me, who cares?”

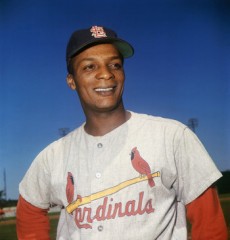

Curt Flood was the player that Miller found to try to test the Reserve Clause in court. Flood was a St. Louis Cardinal outfielder traded to the Phillies in 1970 against his wishes. The antitrust case the Players Association filed on Flood’s behalf made it to the Supreme Court in 1972. The Court sided with MLB. However, at the same time, the Court decided that the antitrust exemption was a little fishy, though not a matter the Court could overturn.

The owners were in a bind. They were leery of continued scrutiny of the antitrust exemption, and the players have proven that they were willing to act collectively with a threatened strike in 1969 and a four-day strike in 1971. In 1972 they agreed to arbitration, as a concession to players that would not affect the Reserve Clause. Arbitration was a fascinating little test of wills: each of the player and the team would propose a salary figure, and the arbitrator had to choose one or the other. So if your bid was too high or too low, you risked being the cause of the other guy winning. But it ended up being beneficial to players, as arbitration was at least some form of leverage, and pay began to climb.

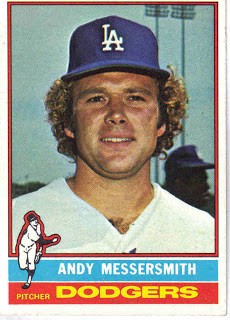

Free agency finally came on somewhat of a technicality. Dodgers pitcher Andy Messersmith managed to pitch the 1975 season without signing his contract. As it was a 19-win season, he was offered a new, lucrative contract. But, since he never signed, he considered the 1975 season to be his option year, and argued that he was actually a free agent. The owners argued that the option was actually the renewal of the entire contract, thus provided for another automatic option year. The claim went to arbitration. The owners lost. Thus opened the barn door, and the Players Association had enough leverage going forward to negotiate on a basis of relatively equal standing.

The Reserve Clause still exists, mind you, but after years of negotiations between MLB and the Players Association, there are arcane rules affecting when and where a player becomes a free agent, able to acquire the full value of his market value, or at least spend a quiet year in Miami.

Why does the average baseball player make three million dollars a year? Because the average baseball player is a member of one of the most powerful unions in America.

KNOW YOUR ROLE, ROOK

For the record, the above figures are the average player salary and not the median salary — each number is intended to be the aggregate of all player salaries divided by the number of salaries, and not the statistical “middle” salary. And as we know that sometimes players make unimaginable amounts of money (i.e., A-Rod’s $28mm due for 2013), is it possible that the average salary is inflated as the free agency era starts roaring by gains at the top and not by gains for all players?

There is a way to look into this. In preparation for negotiations with MLB over a new contract, in 2009, the Players Association prepared a report on players’ salaries [.pdf], which included a very useful exhibit on 2008 average salaries by position. This is useful to see if there is a pull from the top, as players’ salaries are only included if they played in 100 or more games (except for pitchers and DHs), so that rookies and journeymen, presumably paid at the lower end of the scale, are excluded.

The overall average (in 2008 dollars, as are all amounts in the paragraph) was $3,154,845. Meanwhile, the average salary for a short stop was $4,959,658, and for an outfielder, $5,538,821. The highest is the DH (which is why we should detest the American League) at $8,488,360, but there are actually two positions that average out at lower than the overall average: second base ($2,905,771) and relief pitcher ($1,655,710).

This highest position average is a little more than two and a half times the overall average, and the lowest position average is about half the overall average. The numbers don’t seem to be artificially inflated by growth at the top.

But hell, for the giggles, let’s also look at the player salary minimum, as mandated by the applicable collective-bargaining agreements, the increase of which Marvin Miller worked so hard to obtain (again, inflation-adjusted figure in parentheses):

1964: $6,000 ($44,935)

1965: $6,000 ($44,222)

1966: $6,000 ($42,994)

1967: $6,000 ($41,706)

1968: $10,000 ($66,714)

1969: $10,000 ($63,260)

1970: $12,000 ($71,804)

1971: $12,750 ($73,089)

1972: $13,500 ($74,982)

1973: $15,000 ($78,434)

1974: $15,000 ($70,639)

1975: $16,000 ($69,046)

1976: $19,000 ($77,525)

1977: $19,000 ($72,791)

1978: $21,000 ($74,777)

1979: $21,000 ($67,155)

1980: $30,000 ($84,526)

1981: $32,500 ($83,008)

1982: $33,500 ($80,596)

1983: $35,000 ($81,584)

1984: $40,000 ($89,381)

1985: $60,000 ($129,461)

1986: $60,000 ($127,098)

1987: $62,500 ($127,732)

1988: $62,500 ($122,657)

1989: $68,000 ($127,317)

1990: $100,000 ($177,632)

1991: $100,000 ($170,460)

1992: $109,000 ($180,371)

1993: $109,000 ($175,129)

1994: $109,000 ($170,756)

1995: $109,000 ($166,050)

1996: $109,000 ($191,288)

1997: $150,000 ($216,978)

1998: $170,000 ($242,136)

1999: $200,000 ($278,711)

2000: $200,000 ($269,645)

2001: $200,000 ($262,186)

2002: $200,000 ($258,106)

2003: $300,000 ($378,532)

2004: $300,000 ($368,713)

2005: $316,000 ($375,650)

2006: $327,000 ($376,579)

2007: $380,000 ($425,495)

2008: $390,000 ($420,546)

2009: $400,000 ($438,869)

2010: $400,000 ($425,883)

2011: $414,500 ($427,817)

2012: $480,000 ($485,377)

At the beginning of this era, the minimum salary was about a third of the average salary. By 1979, as free agency was beginning to take hold, the minimum was a sixth of the average salary. And by last year, that ratio was more like one-seventh. Definitely, the salary growth at the top has been dragging the average salary upwards.

Having said that, it would be hard to find anyone who would not want to enter a career at the starting salary of $485,000. If your kid is a tall left-hander with a propensity to throw things, it would be difficult to resist the urge to nudge him into a possible pursuit of a baseball career.

It’s easy to complain about this. “It’s a bunch of dudes playing a kid’s game!” you protest. That may be the case, and begrudging success of people who work for someone else is a peculiar trait of Americans. But the truth of it is that it never was a kid’s game. It was a grown-up’s game, from the get-go, and an enormously successful business endeavor, one that opened the door for all the football and hockey and basketball players (and team owners) to commodify what was once a leisure activity. And for decades, other than the superstars, the economic benefit of this success sat in the pockets of the League, and the team owners. The stratospheric increase in the salaries of baseball players is the story of the singular success of organized labor, and those big contracts are nothing but management, sometimes against their will, sharing the fruits of the labors of their employees.

Previously: How Much More Are Movie Stars Making Today?

You might also enjoy: The Cup Of Coffee Club: The Ballplayers Who Got Only One Game

Brent Cox is all over the Internet. Photo of Rodriguez by Keith Allison.