Interviews With The Survivors

by Matthew Shaer

A couple of years ago, I took the train out to Long Island to interview the last person pulled alive from the wreckage of the Twin Towers. Genelle Guzman-McMillan had been in her early 30s on September 11, 2001, and employed by the Port Authority, which had an office on the 64th story of the World Trade Center. She and her coworkers had managed to make it out into the stairwell and all the way down to the 13th floor before the second plane hit, after which the entire building collapsed and Guzman-McMillan was buried under several thousand tons of debris and dust. She lay there for 27 hours, a few inches away from a corpse. Finally, she was found by a search-and-rescue dog. A miracle, the media called it.

By the time I met Guzman-McMillan, a decade had passed since the ordeal, and she seemed fully healed, both emotionally and physically. She told me her story clearly and calmly, in an unwavering voice. Sometimes she smiled. Once, her eyes filled with tears, but she quickly regained her composure. After about an hour, her husband and two daughters returned to the house, and she showed me to the door. I went home and transcribed the interview and wrote the whole thing up. The short article on Guzman-McMillan appeared in August of 2011, in New York Magazine’s 9/11 encyclopedia. I think Guzman-McMillan was happy with it.

I mention all of this as a way of getting at how thoroughly the experience contorted my view of what it means to write about tragedy — and more specifically, what it means to write about tragedy through the eyes of a survivor. In some ways, Guzman-McMillan was an anomaly. She claimed that she’d never once seen a shrink, never had bad dreams about the towers collapsing; she’d found God in the rubble, and she planned to help others do the same. (In fact, she still speaks frequently to church groups.) That was enough for her. Moreover, she’d had ten years to process the tragedy — time doesn’t heal everything but in certain cases it can provide a bit of padding.

***

In early November of 2012, I saw an article in the Times about the Bounty, a tall ship that had sunk during Superstorm Sandy, leaving one sailor dead and the captain missing at sea. The lead art was a photograph — I later learned it had been snapped by a Coast Guardsman, on his iPhone — of the Bounty slipping under the wind-chopped Atlantic. It was terrifying and surreal and hauntingly beautiful and I knew right away that I would try to write about the doomed boat and her crew. I took it for granted that other magazine writers were thinking the exact same thing (and I was right).

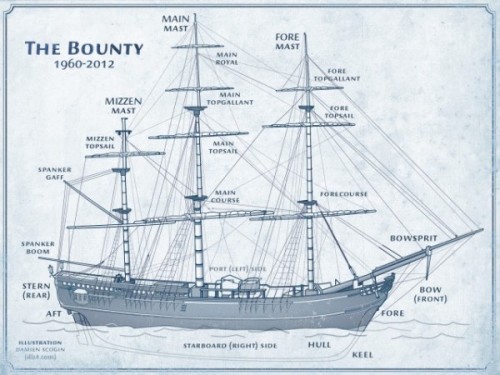

But I figured there was more than enough in this story to go around: There was the history of the boat, which had been commissioned in 1960 for the Marlon Brando version of Mutiny on the Bounty, and was subsequently saved by Brando himself; there was the motley crew of 20-somethings and retirees and the insular tall ship community; there was the headstrong captain, Robin Walbridge, who had made the decision to sail around and then through storm, when he should probably have laid Bounty up in port.

In the end, I caught a lucky break: a well-known adventure writer (a writer much better than me), who had been mulling a story on Bounty, decided against taking the assignment from a major men’s magazine. That left me and a reporter for Outside, which was racing to prepare a Bounty piece of its own. Still, Outside faced space and timing constraints, and it was unlikely its writer would be able to both hit her deadline and attend the February federal inquiry into the sinking of the Bounty. I was going to write my piece for The Atavist, a digital publisher that allowed its writers unlimited space and some flexibility on timing — since The Atavist does not release a print edition, I could go to the hearings, in the Navy town of Portsmouth, Virginia, record what I saw, and have the whole story to my editor just a few days later.

But I was completely unprepared for how difficult the process would be. Many of the sailors had taped a segment “Good Morning America,” in early November; a handful had also appeared on a Weather Channel documentary produced by Al Roker. And yet no matter how many Facebook messages and emails I sent, no matter how many phone calls I made, I could not secure an interview. Selfishly, this infuriated me. I thought of Guzman-McMillan, who had so willingly talked to me. If she could talk about what she had experienced, why couldn’t the Bounty sailors? And why wouldn’t they want to? I was offering them a platform — a chance to tell their story.

Here’s the place where I nod to Janet Malcolm’s famous quote from the very first page of The Journalist and the Murderer: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible.” In hindsight, I think I can claim both stupidity and egoism (take that, Janet!). There are very good reasons to write about a tragic event, of course: to explicate catastrophe and help to keep something similar from ever happening again; to draw attention to malfeasance and highlight heroism; to sate simple human curiosity. The sinking of the Bounty had caught the world’s attention, and plenty of people — me included — wanted to know exactly what had happened on board.

And yet when I sat down to type out messages to the survivors of the Bounty, when I dialed them up at home, I was thinking less about the nobility of the enterprise — or for that matter, the feelings of the survivors — than what it would take to get the story written.

***

In the end, I managed to get a few sailors to talk to me. For the first interview, I flew out to Oakland; the second took place over the phone. In the latter case, the survivor talked a blue streak for two straight hours, more or less uninterrupted by my questions: he recalled what it was like to be sucked underwater with a sinking ship, what it was like to almost drown, what it was like to believe without a doubt that you were dying.

It obviously hurt him to talk about it, and he hung up pretty hurriedly. I probably should have called him back later to ask how he was doing — to thank him profusely for taking the trouble to relive a tragedy. But again, I concentrated solely on the quality of the copy, and how thrilled my editor was going to be. I haven’t talked to that survivor since.

On the other hand, I do fully believe that reportage about tragedy can help us better understand the world around us. In 2011, I wrote a story about Leiby Kletzky, an eight-year-old Hasidic boy murdered by a mentally troubled man named Levi Aron. I built the narrative around the efforts of a local Hasidic man, Yaakov German, to crack the case; indeed, German helped lead investigators directly to Aron. The murder itself was unspeakably brutal, but German’s efforts to find Kletzky’s killer seemed to me indicative of a better part of human nature — the part of us that cares deeply for others, that wants justice to be done. I remain proud of that article and the reception it received.

I just wish I could always approach all stories the same way.

***

I went to Portsmouth. I sat through the hearings. At one point, a young sailor named Laura Groves took the stand. I had attempted to contact Groves several times, but I never received any answer. Later, I’d phoned up a former hand on the Bounty, who had not been on the boat at the time of the sinking, but was in touch with plenty of folks who were. I told him I was working on a short e-book for The Atavist, and asked for his help reaching Groves and others. (The Atavist doesn’t publish e-books, exactly — the stories are more like multimedia-enhanced “mini-books,” or really long articles. Still, it remains easiest, in most cases, to describe them as e-books.)

So Groves knew about my project, as did most of the survivors. After about an hour on the stand, the lead Coast Guard investigator asked Groves to describe the scene on deck while the crew was preparing to board the emergency life rafts. Groves indicated that most of the sailors were calm, although one was clearly panicking and scared. The investigator asked Groves to say aloud the name of that sailor. Groves shook her head.

She would write it down, but she’d prefer not to say it out loud. There were journalists in the room, she said. “They are people writing books about this,” she added, practically spitting the words.

I’ve been a professional journalist for about seven years. I’ve worked full-time in the newsrooms of two major papers. But I have never shared the bloodhound-like instinct of the tabloid reporter. Having a door slammed in my face does not energize me. It dejects me. I read the comments sections of my articles with one hand half-covering my eyes.

Hearing Groves say those words was just as good as getting a knee jammed into my gut. The air went straight out of me.

A couple days later, I relayed what Groves had said to a magazine writer friend (the same writer, incidentally, who had chosen not to write about the Bounty). He emailed back the following:

Of course it’s easy to forget, in the pursuit of a good story, how much higher and more personal the stakes are for the people who actually endured the thing. You’ll move on, we’ll always move on to the next one, but the people who’ve lived through it have to live with the way its been represented. I remember an interview, years ago, with a woman whose daughter was killed in the Oklahoma City bombing, that famous picture of the firefighter carrying the dying baby. It had been turned into a memorial statue, and the woman told the interviewer that she just wanted her daughter back. Always good to keep those human impacts in mind.

Wise words, and I’ll try to remember them as long as I write.

Unfortunately, my friend is all too correct that all nonfiction writers move on. We bounce from one article or essay to the next. And it’s in that moving on — that constant search for a bigger and better and more incredible story — that we can often allow ourselves to forget what, exactly, is at stake.

Matthew Shaer is the author of The Sinking of the Bounty: The True Story of a Tragic Shipwreck and its Aftermath, which is available via the Atavist iOS app or as a Kindle, Barnes and Noble, or Kobo e-book. He tweets at @matthewshaer. Top photo courtesy of the US Coast Guard; diagram of the HMS Bounty by Damien Scogin for the Atavist.