One Last Ride For Paul Walker: "Fast" Fans Rally On Echo Park

by Hayley Terris

I discovered news of Paul Walker’s passing the way we all discover celebrity deaths these days. My friend Rick had posted a filtered picture of a candlelit vigil with the description, “Here’s a shitty photo of the impromptu Paul Walker memorial service at the house that, apparently, the first Fast & Furious movie was shot at in Echo Park. It was weird.” He added a hashtag: #RIPPaulWalker.

My first thought was, “Aww man, Paul Walker was so hot. He’s dead?” Paul Walker! The apex of high school goy fantasies, the chiseled matinee prince of my 90s adolescence. The non-Dawson in “Varsity Blues.” The only man ever who could get away with wearing frosted tips and still look hot.

My second thought was, “Uh, that’s my block.”

Just then, I heard the tremulous roars of eight be-spoilered cars outside my home as a caravan of souped-up cars pulled up, double parked, and started taking pictures outside my neighbor’s house. This continued for the next 48 hours. Indeed, it was weird.

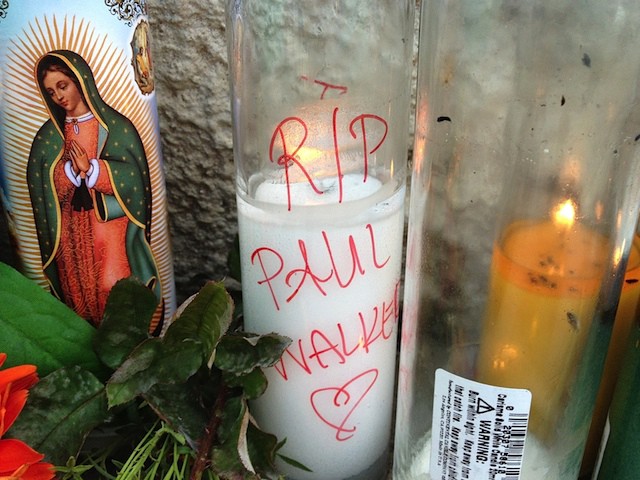

I now live next door to the unofficial Paul Walker memorial, an impromptu shrine dedicated by a smattering of car enthusiasts and mega Fast and Furious fans looking for a place to mourn the loss of their favorite actor.

Yes. Paul Walker was very hot. Again, he pulled off frosted tips with a suaveness that Guy Fieri could only dream of. And, according to the public outpouring of love from his famous friends on Twitter, he had a reputation of being a chill, sweet, and incredibly generous guy. It may not have been so obvious in life that he had a massive following — not to me at least. But Paul Walker is adored.

“He was like this generation’s Steve McQueen. He was the Wayne Gretzky of cars,” said Jacqueline, a visiting emotional Fast fan with a thick French accent and an effusive passion about the deceased. She’d trekked to this nouveau mecca with her two sons.

To me, Walker’s most memorable role was as a high school doucher who bet on the Pygmalionization-potential of the town dweeb and then tried to date rape her at prom. To be fair, I have not seen most of the films Paul Walker made in the last decade. I got through exactly 43% of the original Fast & Furious before dial-flipping away one lazy summer day. Now this is something I cannot admit near my home.

The location next door provided all the exteriors — and some interiors — for the home of Vin Diesel’s Fast character, and out back it has some kind of badass garage. It’s a sweet craftsman with a killer view of the downtown L.A. skyline. Now its front sidewalk is lined with prayer candles, teddy bears, a balloon, signs, flowers, and even a picture of the last photo Instagrammed of Paul Walker, supposedly just thirty minutes before his death.

Mateo, the 15-year-old who lives in the house, was out front, barefoot, as a group of nine people and a baby ambled up. “Last night, there was like a ton of people,” he told me. “People came and had beers and put out candles. Everybody was here. It was crazy. I was in bed and then I heard all these cars just pulling up.” According to Mateo and his dad, the cars and visitors just kept on coming. Hundreds of them a day.

A fresh group of visitors asked to take a group shot in front of the house. Mateo agreed and collected handfuls of cameras and cell phones as the mourners smiled and posed on the front steps.

Jacqueline, her two sons, and their friend huddled around me as more people filled the sidewalk.

“He’s our idol,” her oldest son Teddy said. “We know that outside of film. He is an enthusiast, a hard core enthusiast of cars, just like we are. So to us, it’s like we’ve lost a best friend, we’ve lost a brother. It’s hard.”

Teddy said the first film is what ignited his passion for cars — “and now, over ten years later, that’s our passion for life. We breathe it and live it every day. It’s like, we live that life. We wrench on our cars every night. We go out and drive. It’s crazy. It’s become our life.”

Jacqueline’s a car exporter, and she cites the Fast movies as the catalyst for the avalanche in interest in the car world over the last decade. “After the movie, it exploded,” she said. “Businesses would triple because every young kid wanted to be Paul Walker.”

“Most of us go to the racetrack over the weekend,” Teddy said. “We’ll go race our cars at the track and it was not uncommon to see him at the racetrack driving, in the pit, changing his tires, checking on his engine. That’s why among us, it’s such a shock because he was really one of us.”

“Do you know all these people?” I asked, and motioned to the small mob on the sidewalk, placing trinkets, lighting candles. It turned out they’re actually all strangers, united in mourning by a Facebook event that Teddy created: they made a caravan from Neptune’s Net, a restaurant at the county line in Malibu and a Fast film location, to here.

“These are people who’d never hang out,” Teddy said. “We’ve been brought together. It’s a really diverse group.”

“We’re from all over,” Jacqueline said. “We’re drifters. We drift. But there are AMC — American Muscle Cars — here. Japanese Domestics. Stancers.” She inflected each group individually so I would know that there’s a difference between “drifting” and “stancing” and that this is all very “Sharks” and “Jets” and I probably don’t get the nuances at all. Which is true.

I do understand the compulsion to collectively mourn after a tragedy and am legitimately moved by Walker’s impact on this community. But what befuddles me is “why here?” Paul Walker died in Valencia, 32 miles from here. Paul Walker’s character didn’t even live in this house; they just shot some scenes here. This is just one of dozens of locations where he shot over the span of his career.

Why here? And how long was this all going to last?

I asked this of Jenny Pachucki, an oral historian and assistant curator at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, as well as Adjunct Professor of history at Wagner College in New York. She’s an expert in this type of public mourning.

“Temporary memorials are interesting because they really are grassroots efforts that are democratic spaces; anyone can come and contribute what they like wherever they feel like leaving it,” she said.

My little street has become a memorial zone as a matter of accessibility and convenience. “After the September 11 attacks, Union Square — located miles from Ground Zero — became a locus for temporary memorials,” she said. “It was a central, public location that was accessible to the public in a way that Ground Zero was not and it had a history of public gathering. As with the case with the Paul Walker crash site, it is probably not an easy place for the public to access (nor particularly safe) and while it is significant in that it is the site he died, the crash site holds very little symbolism to the life that he lived.”

“The notion of media attention,” she said, “especially in a circumstance like this, cannot be discounted either. I think these sorts of sites are also conducive to ‘dark tourism’ and allow the public access and to feel like they are insiders on the life of the person who was killed.”

Jenny also mentioned that the lifelines (no pun intended, but I’ll take it anyway) of these shrines are fleeting: “The items left are not meant to last or withstand the elements and the memorial will naturally have run its course as the things brought to the memorial — flowers, candles, etc. — do too.”

So our Echo Park car enthusiast mecca will soon shrivel up like the wilting carnations on the sidewalk. But not if the uber fans have anything to do with it. To them, Walker’s death has a deeper implication — both for them and the box office. Universal was still in production of the seventh installment of the franchise and it’s unclear if Walker had actually finished his participation in the film. There’s talk from some of the mourners that he was supposed to do pick-up shots in the New Year. There’s talk from others that the entire movie will have to be rewritten to reflect his death — a 90-minute, nitrous-filled, snappy-dialogue-laden “In Memoriam” to the character who served as the linchpin of the franchise. This shit is, like, heavy.

“All the French fans want us to do a thing to put somewhere in his honor,” Teddy said. “It’s, like, an international loss.”

“A permanent memorial?” I asked. “Where would you put it.”

“Here,” he said. Teddy looked over at the homeowner, who gave a thumbs up. Uh oh.

Hayley Terris is a writer and producer who does many things on the interwebs. Some of them are interesting. Most of them are embarrassing.