What Happens To Queens?

by Tom Lisi

While we’re all assessing the Bloomberg legacy, we should remember a wonky but big part of the city’s transformation in the last dozen years: the rise of the Business Improvement District. Of New York City’s 68 BIDs in operation today — the latest being the hard-fought SoHo BID — 24 were founded since 2002. The BID model runs the gamut from corporate-financed midtown groups, like the 34th Street Partnership, to smaller outer-borough associations that pool money for holiday lights and maybe pay for some extra street cleaning and trash removal. They have taken up roots and cleaned up their areas — and now several are looking to extensively widen their borders, including one in Jackson Heights, Queens.

In terms of the large-scale private development for which Bloomberg will be remembered, Queens quietly chugged along while Manhattan and Brooklyn exploded. But, in the last few years, the approval of the thousand-unit 5Pointz luxury towers, the Willets Point mega-huge mall, the 7 train extension, and the USTA Tennis Center expansion have changed all that. New construction permits in Queens have outpaced permits in Brooklyn in two of the last three years.

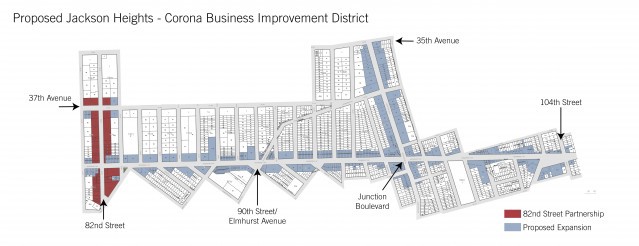

The vision that developers and City Hall have for Queens it still a little difficult to decipher, but one thing is for sure: they want people taking the 7 to that enormously huge mall. (How huge? The mall is approved to be 1.4 million square feet.) At the same time, the proposed additions to a small BID would acquire a large portion of one of the most economically viable areas left in Queens: it extends 20 blocks from 82nd Street into Corona, and stops close to the Willets Point project site. (Previously, it went 10 blocks further, up to 114th Street, before planners found out the stretch was mostly residential.)

The area is one of the densest commercial corridors outside Manhattan. Spearheaded by the 82nd Street Partnership — that’s landlords, a bank, and outgoing Comptroller John Liu, basically — the proposal would expand the organization from covering a bit more than 100 businesses to perhaps 1,000.

On paper and in before-and-after pictures, the BID model seems like a fairly straightforward, pro-neighborhood godsend. “BIDs are completely locally driven initiatives — property owners, business owners coming together and wanting to do more for their commercial corridors to make it a cleaner, safer, better place to do business,” said Kris Goddard, executive director of the Neighborhood Development Division of the city’s Small Business Services. His job is to make BIDs happen.

And while BIDs do provide their small businesses with valuable services, they answer to landlords — and to City Hall. The ambitious Jackson Heights BID expansion plan originates from Council Member Julissa Ferreras and SBS Commissioner Robert Walsh, who recruited Seth Taylor as the executive director of the 82nd St. BID. Formerly of the Union Square Partnership and Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, Taylor almost immediately changed the group’s name to include the word partnership. A year later, Ferreras and Commissioner Walsh unveiled the expansion plans to the public.

Ferreras is looking to totally revitalize the corridor with her “New Deal for Roosevelt Avenue”; Taylor’s leadership on the BID is an important piece. The BID “deepens their roots into the district; by investing in it they become stewards of the neighborhood, they become more involved in the planning and the decision-making about the future of this commercial corridor,” said Taylor.

There’s no getting around that the corridor’s overflowing trash cans and sidewalks caked with dried pigeon droppings fallen from the train tracks are not popular features for local residents or commercial developers. The bane of local politicians are the infamous chica chica cards, handed out to passers-by. As you get away from the 74th Street subway hub and closer to Corona, vice is common, some of it spillover of criminal activity originating overseas.

Even so, with the Willets Point project, and the encroaching economic vitality of Chinese-dominated Flushing, the investment potential on Roosevelt Avenue is enormous. “Roosevelt is not a goldmine, Roosevelt Avenue is a rough diamond. Once it’s polished, it’s going to be priceless,” said Eduardo Giraldo, an insurance broker for businesses in Jackson Heights, and former vice president of the Queens chapter of The Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. Giraldo lost to Ferreras in the district’s 2009 Democratic primary race for city council and though he is a de facto leader for the mostly-Latino constituency of small business owners in the area, he seems to keep losing friends in the controversies surrounding the borough.

Historically, Giraldo is not necessarily anti-private development — he’s previously come out in support of WalMart coming to New York, and also tried to pick a fight about the city’s alleged mistreatment of Willets Point residents in their relocation efforts, calling the locals’ existence “modern slavery” in the New York Times. On the BID, he’s not entirely opposed, but says the version being touted by Taylor is designed to clean out the corridor for national chains. He wants a provision in the BID that mandates a third of its 1,000 businesses be minority-owned. “If we can get that, that’s a big win for us,” he said.

In interviews, Taylor and and Giraldo have both tried to discredit one another as myth-makers. Taylor says the BID is specifically designed to help the mom-and-pop businesses compete, and has not even heard of Giraldo’s proposal. “It’s not even within the realm of what a BID can do. That would take legislative action,” Taylor said. He is also dealing with the Roosevelt Avenue Community Alliance, an organization of local businesses that are fervently against the BID altogether. Their view is that a BID is just a way to fast-track gentrification.

Getting overall support from current business owners has required a bigger-than-expected outreach campaign from the 82nd Street Partnership. The business owners get to vote on the plan in a ballot that Taylor says will go out in early 2014. “Roosevelt Avenue is very disorganized in a number of ways,” Taylor said. “The business community has not been organized. The public spaces, you haven’t seen a lot of investment in them. So this is an opportunity to organize the business community, to create a vision for the future of the neighborhood, and to invest and implement that vision.”

The proposal is certainly a no-brainer for landlords who will likely reap the benefits faster than anyone. They can also pass the BID’s assessment fees over to the tenant’s rent. A couple of the locally strong real estate firms, including TZM and Lewis & Murphy, are at the table for getting the BID expansion in place, but many of the storefronts have been owned by the same family for generations. There’s also the odd business owner on the strip who managed to save and buy their storefront at the right time.

Given what the BID intends to do with the assessment money — provide better lighting, remove graffiti, make more outdoor spaces and events — it’s easy to see how yet again how a BID will lead to greater desirability, and leave a lot of the small businesses that provide services to the largely immigrant populations in the dust. Cue Chipotle.

To add to the confusion, Make the Road New York, an immigrant advocacy group with two members on the proposal’s steering committee, has come to the aid of Taylor’s outreach efforts, but has not come out publicly one way or the other on the expansion plan and declined requests for an interview. “They want to make sure, like us, the business community has all the information that they need to have to make an informed to decision. Once they gauge how their members stand on this, they may come out and publicly support this proposal,” said Taylor. They may.

Community members who look at the BID with skepticism hold out some hope that the incoming de Blasio administration might halt the momentum of 82nd Street. Ferreras is a member of the ever-strengthening City Council Progressive Caucus, and with an unorganized, politically quiet immigrant constituency, she serves her district with a lot of leeway. Unlike SoHo, it could happen fast. Taylor said that if the proposal gets enough support from the community in the mail-in vote, the process of approval and implementation could take as little as nine months.

Tom Lisi is a writer and comedian in New York. He lives in Queens. Photo by The All-Nite Images.