I'm Going To Leave You With This Meditation on "Major Tom" by Peter Schilling

The German version, obviously. (IT’S A METAPHOR).

Even if you’re a walking fetus, i.e. a person in their twenties I don’t understand, you have probably heard at least a snippet of the third-best song of the Neue Deutsche Welle, “Major Tom” by Peter Schilling. (#2: “Der Kommissar”; #1: “99 Luftballons;” this is not up for discussion.)

But the version you have probably heard of this haunting masterpiece, which 100 percent encapsulates my fee-fees on any given day, is Schilling’s English translation, released in September of 1983—approximately nine months after German original. Both versions are an homage to “Space Oddity,” and both have a relatively unnecessary parenthetical in their titles. (I’ll never accuse a German of under-explaining anything.)

The English, which peaked on the Billboard Hot 100 at #14, is called “Major Tom (Coming Home).”

The original, meanwhile, is “Major Tom (Völlig Losgelöst),” which literally translates to completely detached.

I’m not going to lie; unlike the decidedly inferior English version of “Luftballons” (love Nena forever but it’s true), “(Coming Home)” has a lot going for it, in precise (and unassailable) order of importance:

- Schilling’s German accent in English (eye-heart emoji);

- The countdown (that countdown RULES);

- The very poetic chorus.

It will surprise precisely zero people that the English version is full of evocative phrasing and the German version is entirely literal, and thus has to do all of its evocative heavy lifting with the uniquely Teutonic plasticity of its language. WHICH YES, I AM GOING TO TALK ABOUT, in this, my very last column for The Awl, as it prepares to detach from us and launch into the endless dead space of the retired internet forever.

Look at the airy English second verse, which works, as so many of our pop songs do, in snippets:

Control is not convinced

But the computer

Has the evidence

No need to abort

The countdown starts

Now check out the very literal original, which I have translated as literally as possible to retain maximal literalness, and also which I have provided with my very last Awl Dubious German Phonetic Pronunciation Guide, my parting gift to you:

Experten streiten sich

(ex-PAIR-tun sTRY-tun SIK)um ein paar Daten

(oom AYN PARR DAH-tun)die Crew hat da noch

(dee KRUU HOT dah NOK)ein paar Fragen

(AYN PARR FRO-gun)doch

(DOK)der Countdown läuft

(dayr KOWNT-daun LOYFT)

Experts fight amongst themselves

About some data

The crew still has

A few questions

AND YET

The countdown runs

All of the work in that verse—ALL OF IT, you guys—is done with one word, a supremely awesomely placed doch. This is a word first-year German professors unfortunately call a “flavoring particle” and then caution non-native speakers never to use, because its truly correct use—like the German cashier’s ability to know precisely how pedantic one should be to any particular grocery store customer—can never be learned.

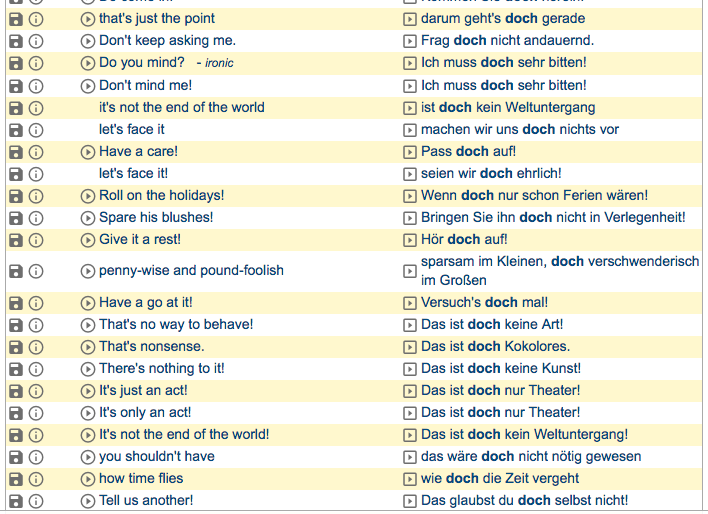

Here are just a few of the way doch works in a sentence, courtesy of LEO, the world’s best, most trusted and least judgmental online German-English dictionary:

The real genius of “Völlig Losgelöst” is, however, in Schilling’s variation on a different word. (Alas, that word is not Erdanziehungskraft, the German word for gravity that literally means “Earth-pulling-to-power,” but how wonderful is that?)

Let’s take a look now at the English chorus, which, like I said, is poetic and evocative, hooray:

Earth below us

Drifting, Falling

Floating weightless

Calling, Calling

Home

Great. Yes, I like it and you do, too. But. Now look at the original, specifically the word schwerelos (SHWAY-ruh-LOESS) at the end, which is the German for “weightless”:

völlig losgelöst

(FOO-lik LOESS-guh-LEEEEUST)von der Erde

(fone dayr AIR-duh)schwebt das Raumschiff

(SHWAYBT doss ROWM-shiff)völlig schwerelos

(FOO-lig SHWAY-ruh-LOOOESSSSSS)

Here’s a literal translation:

Fully detached

From the Earth

The spaceship floats

Totally weightless

In the first chorus, you’ll hear, Schilling brings the final syllable of schwerelos down, alighting steadily on a single note, offering a sort of uneasy ease that implies that Major Tom and die Crew expect the Raumschiff to land safely, but whose slight warble still hints that shit is about to go awry.

The second chorus, meanwhile, steps that los down two notes, and coincides it with a vroomy sound effect that hints to us: Hey, Tom is now officially lost in space but maybe he kinda likes it?

And then, the final chorus: Schilling repeats it three times—and on that last syllable, the word los takes off on its own and soars, repeating, into Schilling’s upper register until it fades.

The word los is, you see, not merely an awesome suffix meaning -less as in without (weightless; hopeless, etc.), and simultaneous prefix meaning de- (detached).

Los is also, my friends, its own word all by itself—and it means, among other things, fate.

It also means gone.