Hot Rocks

A short story.

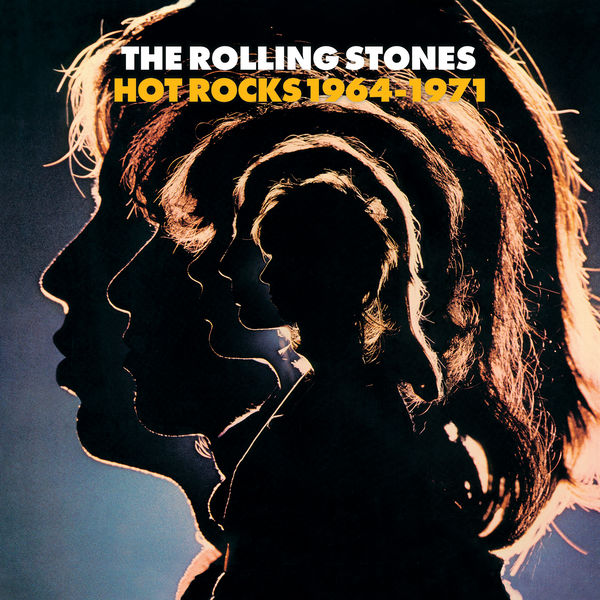

Evan turned eleven on Groundhog’s Day. Berch, his after-school and summer babysitter, gave him his beat-up copy of the Rolling Stones’ Hot Rocks double LP. Berch, who was sixteen, told Evan that he had lost interest in the Stones on New Year’s Eve, when he heard the Sex Pistols for the first time.

There were black-and-white photos on the inside spread. “That’s Bill,” Berch said, pointing to a man wearing what Evan thought was a ladies’ jacket. “He hasn’t said a word to anyone since the day he joined the band. That’s Brian.” Berch pointed to a blond man with bangs in his eyes. “He was murdered. And that’s a bad shot of Charlie, and those are Mick and Keith.” Berch wagged his finger between two men: one was lighting a cigarette; the other had long hair and a lady’s face. “There too.” He tapped a photo of a guy who had hair that stuck up and out.

“Mick with the hair?” Evan said. He hadn’t heard the name before.

“Keith. Keith.”

“How does he get his hair to do that?”

“What, spike up? You have to have men’s hair to do it. It gets stiff when you’re an adult. Like a head beard.”

Berch brought the photo of Keith a few inches from his own face. Now Evan couldn’t see. He noticed how big the space was between Berch’s nose and top lip. He wondered if this was what made Berch so ugly. Or maybe it was that his mouth was usually open. Berch talked a lot, especially about drugs, women, and music. Even if Evan wasn’t interested, he listened to be polite. His dad said that he had to have a babysitter until he turned twelve, and Evan didn’t want Berch to quit. Two years ago, Berch was the only person to answer the ad that Evan’s dad had put up on telephone poles in the neighborhood. If Berch quit, his dad would have to find someone else. That would be a pain in his dad’s ass. And Evan could get stuck with somebody worse than Berch.

Berch handed Evan the record. “I don’t think I should let you get too impressed with Keith. He’s done a crate of drugs. If it wasn’t for cigarettes, he’d be dead now. The smoke works like helium. It gets inside and holds your body up. Anyway, in any picture where you see Keith’s left arm, you’ll notice it’s nothing but target practice. By that I mean track marks.”

“I know,” Evan said. Berch had explained what target practice was when he told Evan about the Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious.

Berch folded his arms. His stomach made his black T-shirt bulge in the front. “The Keith thing is typical for guys your age. I’ve had my fill.” He took a cigarette from his back pocket and put it above his left ear. His long snaky hair reminded Evan of a Cro-Magnon guy’s. “Play the thing until you think the room starts shrinking. Something will happen.”

“Really?”

“Yepper. This record will change your whole little life.”

![]()

Evan knew he was obsessed with Keith Richards. He could remember feeling this keyed up about Aquaman when he was six, and later about the White House: he’d been desperate to move to DC because Somerville, Mass, was kind of ratty, and he thought he and his dad would be safer if they lived near the president. One thing about Keith was, since Evan’s classmates were all into terrible music, he was Evan’s private find. Also, Evan knew that Keith had seen a lot and could tell him things that no one else could. He wasn’t like Berch, who got everything from magazines.

It was summer now, so Berch came weekdays at seven thirty—Evan’s dad worked long days at a printing house—and fell asleep on the living room couch almost as soon as Evan’s dad drove away. When Evan’s dad got home, Berch would sometimes stick around and talk to Evan, who would have rather played his records alone in his room. The two times his dad asked Berch if he wanted to stay for dinner, Berch did. Evan felt nervous both times.

Mornings while Berch slept on the couch, Evan would put on his headphones and play Stones records and read books about the Stones or write letters to Keith. He’d ask personal questions: Where did he get the clothes he wore in photo shoots? What schools did his kids go to? Could Evan have front-row tickets and hang out backstage if the Stones toured again?

When he woke up, Berch would insist on reading each letter, even if Evan had already sealed the envelope. Then Evan had to find and address a new envelope. Evan mailed the letters to Keith’s place in New York City—Berch had traded his Ozzy fan club membership to a kid at his school for the address. Berch said that Keith, Cher, and Muhammad Ali all lived in apartments above Tower Records in Greenwich Village. Berch said it was a fact that Cher made Keith fudge while he walked her dogs at five a.m.

One morning, Berch put Evan in a headlock as soon as his dad left. “How many letters have you sent Keith?”

“I don’t know.”

“Guess.”

Evan did the math in his head. “Around ten. Maybe thirteen.” He’d been trying to write every other week.

Berch let him out of the headlock, put a palm on Evan’s forehead, and left it there. “This came to me last night in a drunken vision: no one likes to write other people back, right? So, we send Keith something easy to answer: a fill-in-the-blanks postcard. We stamp and self-address it. We put it in an envelope and mail it to him. It’ll take him a second to fill out. No mess, no searching for a stamp or the right thing to say. He’ll love it.”

Evan tried to back away from Berch’s hand, but Berch followed him into the kitchen. “What if he isn’t home?” Evan said when he felt a round metal drawer handle on his spine.

“His wife’ll be there. She’ll forward it. What else does she have to do now that she quit modeling?”

Evan knew that Keith’s wife had quit modeling so that she could devote all her time to being a mom, which took a lot of time, but he didn’t feel like explaining this to Berch. He had to admit that Berch’s idea was a good one.

He followed Berch into his dad’s bedroom. Berch sat down at Evan’s dad’s desk. He found a yellow pad in one drawer and a pencil in another and nudged Evan’s gut with his sneaker. “Hit me, my son.”

Evan and Berch disagreed on the type of sentences that Keith should complete. Berch wanted to grill him about being a rock star; Evan was curious about things that he couldn’t learn from books and magazines: how Keith liked being a husband and a dad, and if he wished he had more than four kids and ever thought about the one who died when he was a baby.

They compromised, and Berch printed on the yellow pad:

“Dear Evan: I, Keith Richards, do these things on a typical day: ___________________. I phone ________ and we talk about ________. I do ___ / do not ___ (check one) hang out with Mick. I play the guitar ___ / do not play the guitar ___ (check one) when I’m on the phone. My favorite guitar is ___________________. I have _____ (a number) guitars. My kids are ___ / are not ___ musical (check one). My favorite band these days (besides my own) is _________. I detest ___ / do not detest ___ / have never heard of ___ (check one) the Sex Pistols. Anything else pertinent: ______________________________. From: __________________.”

Berch fanned himself with the pad. “Excellent. Now find me a postcard.”

Evan felt guilty for doing it, but he went through his dad’s desk. Under a pile of old mail he found some blank postcards of Cape Cod that he knew they gave out for free at the bank. He handed one to Berch.

“Terrible. He’ll think it’s an ad to win a free trip.” Berch threw the card like a Frisbee. It hit the wall and fell; Evan thought of a dumb bird. “The man has zillions and a wife who’d make God weak in the knees—his life’s a vacation. Keep looking.”

At the back of a drawer, Evan found a blank postcard showing a man with four doughnuts stacked in his mouth. He showed it to Berch, who said, “Ha! He’ll totally love it. Keith is known for his sense of humor.”

Evan knew. He grabbed a pen, sat on the floor, and was about to write the sentences neatly on the postcard when Berch snatched the pen.

“No. You’re cleanup crew. Get going.”

When he was done straightening his dad’s desk, Evan went to his room, shut the door, and started reading a book written by a lady who’d had sex with most of the Stones and two of Led Zeppelin.

“I found the envelopes,” Berch said after bombing through Evan’s door ten minutes later. He showed Evan an envelope that he’d addressed to Keith—the postcard, addressed to Evan, had to go inside it. “Except I think your old man’s out of stamps, so I’m going to the P.O. Plus I need smokes. I’ll be back in a sec. Don’t touch the stove.”

Through his bedroom window, Evan watched Berch head up the street. The post office was a five-minute walk away. Berch didn’t even run anymore. It had started when Evan was only nine: Berch had sprinted toward the deli two blocks away—Evan’s dad was out of tuna fish, Berch said, and he swore he’d be gone only a minute—and he strolled back more than half an hour later with smokes but no tuna fish. Evan had wondered if his being alive had just slipped Berch’s mind.

Evan had been terrified the first few times Berch did this, had waited for Berch on the front stoop, his back completely tensed, sure that he’d see a stranger in his house if he turned around. But Evan wasn’t afraid of being alone now—a sign, he knew, that he was outgrowing needing Berch.

![]()

Evan checked for a reply from Keith every day. He knew this was idiotic. Keith was busy.

One morning while Berch slept, Evan brought his tape player into the john and tucked a picture of Keith that he had cut out of Creem magazine into the bathroom mirror’s frame. He shut the door and played the Stones bootleg that Berch had taken from his brother’s car and told Evan he could have. With the scissors his dad used to trim his mustache, Evan cut his hair—dark brown, like Keith’s—until it spiked up on the top and sides, only not as randomly as Keith’s. It looked like the fur on a spazzed-out cat.

Berch knocked while Evan was washing his cut-off hair down the drain. “My turn.” Berch opened the door, his face splotchy from sleep. He narrowed his eyes at Evan and stuck out his lower jaw. “What are you doing? You look like a fucking pixie.”

Evan looked in the mirror. “Not really, I don’t think.”

“Yes, really. It looks like that yarn rug in your room grew all over your head.” Berch left and slammed the door.

Evan didn’t agree. He thought he looked good. He seemed to have aged five years since he’d entered the john.

He decided to change into a clean T-shirt—the one he had on was covered with hair. Berch was standing in the hall. Evan walked past him. Berch followed Evan upstairs to his room and stood in the doorway while Evan changed his shirt.

“You shouldn’t’ve done that,” Berch said. “What do you want to do a Keith thing for? It’s been done to death.”

The next morning, Berch appeared with short spiky hair and shades.

“It’s not a Keith thing, it’s a Sid Vicious thing, so don’t say any fucking thing,” he said. “And I’ve been planning to do this for a month.” Berch went straight to the couch. He usually slept on his back, but this time he lay on his front, shades still on, his face in the crack where the couch’s back met the seat cushion. Evan knew that this was so that he wouldn’t wreck his hairdo. He’d never seen an older guy copy a kid before.

![]()

By the summer, Evan was spending most of his time in his room, and sometimes he didn’t bother looking up when Berch came in and started talking his shit. Evan wasn’t trying to be rude, but he liked being alone and didn’t need Berch for anything specific—Evan had even learned to make better sandwiches.

But whenever Evan heard Berch’s friends Scott and Miquel in the kitchen, he’d wait a few minutes and then head down the hall. The three guys together amused him. They taught him card games and sick jokes and called him “Keef.” Scott and Miquel started and won arguments with Berch about which motorcycles were fastest, whether live albums were bad as a policy, whether the Ice Age was coming. Scott, Miquel, and Evan always went into hysterics at Berch’s candlelit basement séances for the dead Stone, Brian Jones.

One broiling Thursday, Berch stacked the kitchen chairs in the corner and everyone lay down on the cool linoleum. Berch was on his back, his T-shirt rolled up to his armpits.

“I’m tempted to piss myself just to feel a chill,” he said.

“Save it for your mother,” Miquel said. Evan didn’t know what this meant, but it was still funny. Evan wondered why Miquel had hair between his eyebrows when he couldn’t grow much on his face. He’d been going for a beard since May.

“Bear in mind that a good tune can have the effect of a wind tunnel,” Scott said. His hair was so long that Evan wondered if he curled it when he was alone. Evan liked Scott. He’d babysat on Saturday night, when Berch had a date, and he’d let Evan watch TV until they heard his dad’s car pull up out front. Evan wouldn’t have minded if Scott sat for him more often.

“Tunes,” Miquel said, wetting his wrists with his Coke. “Where are my tunes?”

Berch lit a cigarette. “Evan. Go get your radio.”

Evan didn’t mind doing what Berch told him to in front of Scott and Miquel. He felt a little bad for Berch. Scott and Miquel were always ragging on him.

Evan returned with his tape player, which had a built-in radio, and handed it to Berch. He sat back down on the linoleum.

“Never,” Miquel said whenever Berch picked a song, and Berch would change the station.

“It’s all just disco,” Scott said. “They call it dance music, but you know better. Huh, Evan?”

Evan did, so he nodded. Evan didn’t know why Miquel laughed then, but he was pretty sure it wasn’t at him.

Miquel finally agreed to what Evan knew was a Stooges song, and a few minutes later, Evan heard the mail plop on the hall floor.

“Evan,” Berch said. “Go.”

Evan got up. Scott tapped on Evan’s sneaker and looked up at him. “Don’t do it unless he says please.”

“Please suck my pud, Scott,” Berch said.

Miquel was scratching between his eyebrows. “Aren’t you kind of old for a babysitter?”

“Shut your butt,” Berch said. “Evan can take care of himself.”

“I was talking to you, Berch.”

Scott laughed, but Evan waited until he was out of the kitchen before cracking up.

Under a Star Market circular and some mail addressed to his dad was the postcard of the guy eating the doughnuts. Evan turned it over.

“Dear Evan: I, Keith Richards, do these things on a typical day: drink, fuck, smoke. I phone _Woody and we talk about music . I do ___ / do not X (check one) hang out with Mick. I play the guitar X / do not play the guitar ___ (check one) when I’m on the phone. My favorite guitar is a 1973 telecaster deluxe . I have 41 (a number) guitars. My kids are ___ / are not X musical (check one). My favorite band these days (besides my own) is none_ . I detest ___ / do not detest X _ / have never heard of ___ (check one) the Sex Pistols. Anything else pertinent: thanks, your card made my day . From: Keith Richards .”

Evan’s skin was crawling. He suddenly had to piss. He brought the card into the john with him and shut the door. Besides the questions Berch had written out, there wasn’t much handwriting on it, and it was messy, but the signature definitely looked right, like what Keith had used on the photos reprinted in Evan’s magazines. He tried to picture Keith at work on the card: using a guitar case set across two milk crates as a desk, minding his blond little daughters who were playing with toy pots and pans at his feet, wearing reading glasses that he’d never agree to being photographed in.

After Evan pissed and flushed the toilet, he sat on the lid for a just a few seconds. He didn’t want to stop looking at the card but thought he’d better get moving: Berch, Scott, and Miquel were bored enough to come after him.

He opened the door. Berch and Miquel each took an elbow. Scott yanked Evan’s heels, and Evan landed on his ass. Berch clutched the postcard. Evan let go because he was afraid it would tear. Berch turned away, Miquel went to look over Berch’s shoulder, and Scott rumpled Evan’s hair before joining them.

“Jesus. It’s from Keith,” Berch said, turning his head to eyeball Evan.

“Holy fuck—it’s postmarked from New York City,” Miquel said.

Evan got on all fours. He hadn’t thought to check.

“I smell Jack Daniel’s,” Scott said. “It’s fucking him, man.”

“They found a pint of Mick’s jizz in Keith’s stomach,” Miquel said.

“Rod Stewart’s,” Berch told him.

“Rod’s jizz?” Miquel said.

“Mick’s jizz, Rod’s stomach.”

“It was probably Evan’s,” Scott said.

Evan stood up. Berch’s back was still to him. Evan aimed for his tailbone and kicked. Berch turned around, raised the postcard above his head, and seemed to look down at Evan from far away.

“You’re sorry you did that.” Evan watched Berch’s face turn the color of doughnut jelly. “Who do you think got you into Keith in the first place?”

“Let’s sell it,” Scott said. “Don’t give it to him, man.”

“What’s it worth to you?” Berch asked Evan.

Evan was so mad that he couldn’t unclench his fists.

“I said, what’s it worth to you?” Berch leaned in. “What’s the matter? Keith got your tongue?”

Evan heard Miquel laugh, but he kept his eyes on Berch.

“Well?” Berch crossed his arms, and Evan worried that the postcard, still in his hand, would bend. “How about kissing my ass?”

“That’s it?” Scott said.

“Kiss my ass, then wash my sneakers.” Berch turned around.

Evan squatted. He kissed Berch’s ass.

“Other cheek.”

Evan kissed the other cheek.

“Sneakers.”

Evan untied them, pulled them off Berch’s feet, went down the hall, opened the door to the basement, where the washing machine was, and tossed them down the stairs. Then he walked back to where Berch was standing.

“Give it now, you fat pathetic loser,” he said, surprised at how quickly the insult had come.

Scott and Miquel laughed as Evan tried to snatch the card each time Berch thrust it toward him before snapping it back. At one point, each gripped a corner with his thumb and index finger. When Berch yanked, Evan felt the card tear, so he let go. He bit Berch on the wrist. Berch yowled, dropped the card, and kicked Evan’s right hip, hard. Evan snatched the card, ran to the basement door, and locked it from the other side.

While Evan was waiting for the wash cycle containing only Berch’s sneakers to end, he decided not to tell his dad about the blue, egg-shaped bruise on his hip because he didn’t want to make him feel bad about not being around. Evan knew that if he just planned for it, he could stand his last six months in Berch’s care.

![]()

Evan spent every day in his room. He often studied the postcard. He didn’t know what Jack Daniel’s smelled like, but he thought the card smelled like cigarettes. He liked looking at the New York postmark. He made a frame out of cardboard and tinfoil and hung the postcard over his bed. The frame hid the tear. He tried gluing rows of thumbtacks along the edges to stick anyone who tried to touch the card, but the glue wouldn’t hold.

One morning while Berch slept on the couch, Evan left the house, crossed the highway, and bought the new Stones LP and a sliding bolt. He knew where his father’s tools were and how to use a screwdriver. Now whenever Berch went for his doorknob, Evan could relax. Sometimes Scott or Miquel tried to get him to come out, but he wouldn’t. Luckily, the three of them went to the deli for smokes a couple times a day, giving Evan a chance to use the john and fix a sandwich. In case of rainy days, when Berch refused to go outside, Evan hoarded jars of peanuts. He hoped his dad wouldn’t wonder why he kept adding peanuts to the shopping list.

One afternoon, Evan heard someone run down the hall and then try his locked door.

“Listen,” Berch yelled. Evan could hear a DJ’s voice coming from what must have been the radio in his tape player—he’d stupidly left it in the kitchen the night before. “Stones tickets,” Berch said. “They went on sale for Foxboro this morning. They sold out in two seconds. The station has a few pairs—you have to be the first caller when a Stones tune comes on, then ID it.” Berch paused a few beats, then: “Are you fucking listening to me?”

Evan said nothing. He heard Berch run back down the hall and felt his body flush with panic. Besides the phone in the kitchen, there was one in his dad’s bedroom, but it didn’t have push buttons. He unbolted his door and tore down the hall.

Berch, Scott, and Miquel were smoking and playing poker on the kitchen floor. Evan grabbed his tape player, which was now blaring Van Halen, from the top of the stove, and brought it over to the wall opposite, where the phone was. He made sure the radio was tuned to the right station and then turned down the volume.

“Cut the fuck, Evan,” Berch said from the floor.

Evan sat on the floor and dialed the station—he knew the number because he used to request Stones songs when he got stuck playing board games with Berch at the kitchen table. He heard a busy signal. He hung up and redialed. He did this every time he got a busy signal.

“I told you: you have to wait for a Stones tune,” Berch said.

Evan ignored him. Anyone who wasn’t stupid knew that there was no point waiting for the song. He needed to get the phone to ring.

Just to roast him alive, Evan decided, Scott and Miquel baked a chocolate cake from a mix. They ate most of it before Berch could frost it with icing he’d made from margarine and powdered sugar. Evan was hungry—his dad hadn’t been to the market in a while and Evan didn’t have any peanuts left—so he snuck a piece after Scott and Miquel went outside to have an icing fight and Berch went to use the john.

Berch shuffled back into the kitchen a few minutes later. He took off his T-shirt, put some ketchup on a carving knife and between his nipples, and lay down. The knife was by his side.

“Any luck?” he asked Evan.

On principle, Evan wasn’t talking.

A minute later, Berch said, “Look, sorry about the other day. You know I think you’re hot fuck. I just didn’t know a pygmy could kick so hard, and I had to keep face, you know? Those guys look up to me.”

Evan didn’t respond.

“Want me to dial? Because I think the cord’ll reach.” He extended his arm toward Evan, who shook his head. “Listen, after this, I can go to the deli for backup batteries for the radio—”

Evan hissed, “You’re not supposed to leave me alone. That’s your fucking job.”

Berch sat up and opened his mouth. Then he wrinkled his nose until it had the texture of a peanut shell. “Don’t be such a pussy. How old are you again, forty? Look, put some ketchup on your neck. Or let me.” He got up, grabbed the ketchup bottle beside him, and reached for Evan.

“Don’t even think about touching me,” Evan said quietly. If Berch laid a hand on him or went for the knife, Evan would smack him on the head with the receiver.

Berch, Scott, and Miquel left when Evan’s dad finally got home at dusk, and Evan untensed his muscles for the first time in hours.

At 10:14, with aching fingers, he won two tickets to see the Stones at Foxboro on October third by correctly identifying the song “Rocks Off.” Somehow he felt less happy than relieved, as if he had just learned that something horrible wasn’t necessarily going to happen after all.

![]()

Evan started sixth grade the Tuesday after Labor Day, and Berch still sat for him after school. Evan wanted to tell someone besides his dad about the tickets, but none of the guys he hung out with at school would care, and he couldn’t tell Berch because Berch would want the second ticket, and anyway Evan still wasn’t speaking to him.

There was a girl in the fifth grade who had spiky hair, only hers was light brown and longer than Evan’s in the back. She often wore T-shirts of bands that weren’t too bad: the Cars, Megadeth, ZZ Top. Evan asked her to go to the concert with him the day she wore a Led Zeppelin T-shirt.

“You must be a messenger of the gods,” the girl said. “Of course I’ll go.” Then she covered her mouth and nose with her hands. “That better not be a Monday. Shit, if it’s a Monday night, I have to babysit.”

![]()

The concert was on a Tuesday night. The girl, whose name turned out to be Nina, got her much older sister to pick up the tickets at the radio station—an adult had to sign for them, and Evan didn’t want to bother his dad. Then Nina’s sister, who said she didn’t care for the Stones and who Evan knew Berch would say looked like a les, drove Evan and Nina to Foxboro. She left them in a traffic jam of cars headed for the stadium’s parking lot.

They walked single file, Nina first, along the side of the road. They passed parked cars whose passengers were scouting for cops while they polished off beers. Evan hoped that no one could tell that he kept getting chills. He barely managed to resist running. It was as if his whole life had been an arrow aiming for this exact place and time.

When they had just made it beyond the mouth of the parking lot, Evan felt someone’s fingers pinching the back of his neck.

“So you did win tickets.”

Evan whipped around. Scott picked him up by the armpits, set him on the hood of a parked car, and pinned Evan’s shins with his hips.

“So?”

“So?” Scott looked from Nina, who had stopped a few yards ahead, to Evan. “How couldn’t you give your ticket to Berch?”

“How couldn’t you give him yours?”

“My cousin owed me for Aerosmith—fucking right I took the ticket. But how couldn’t you, after what Berch did for you?”

“He didn’t want that record anymore. He’s not even into the Stones now—he’s doing the Sid Vicious thing.”

Scott leaned way in. “I’m not talking about a record,” he said to Evan’s forehead. “Don’t you know he filled out the postcard himself and borrowed his brother’s car and drove to New York a couple of Saturdays after you wrote it just to get the postmark?”

Evan didn’t want to, but he considered this. “That’s bullfuck.”

“Why do you think I ended up babysitting for you? Like Berch would have a date on a Saturday night—any night. He wouldn’t even let Miquel out to piss because if his brother missed the car Berch’d’ve been big-time screwed. Plus he couldn’t find his license before he left.”

“Well how was I supposed to know?”

“You honestly thought Richards would bother. Oh my God, are you gullible.” Scott turned to Nina. “What’s it like to have such a gullible boyfriend?”

Nina just stood there for a few seconds. Then she said, “You don’t have a girlfriend.”

Scott brought both hands close to his own face and pointed at her. “Excuse me, but the Stones are about brotherhood, not about sisters, in case you haven’t caught on yet.”

“What’s Berch such an asshole for?” Evan said. “I didn’t do anything to him.”

Scott brought his face so close that Evan could smell shampoo. “This is on record as the nicest thing anyone’s ever done—ever. Berch didn’t want to break it to you that you’d never hear fuck from Keith. And I tell you, Berch’s heart’ll give out when he finds out you’re here without him.” Scott stepped back and pinched his chin, like a professor. “But I guess the last laugh’s on you, since you actually fell for it. Don’t worry, man. At nine I fell for anything too.”

“I’m fucking eleven,” Evan said as he slid off the car.

“Eleven? Wow. Then you really are tragic.”

![]()

Their seats were horrible. When Mick moved his lips, the words didn’t reach Evan’s ears until a full beat later. And Keith was so far away that he looked more like a windup toy than a human. He had a headband around his forehead the way Berch sometimes used to, and Evan found himself getting furious not at Berch but at Keith. Keith had no idea who he was. He wasn’t hoping that a kid from Somerville who’d sent him a cool postcard of a doughnut guy would pop backstage later. The only people who interested Keith were his wife, his own kids, and other rock stars. Evan hadn’t even gotten shivers when Keith took the stage.

Like everyone else, Evan and Nina stood for the entire show. She danced the whole time, which embarrassed him. She was taller than him. During the slow songs, she’d put her hand on Evan’s closer shoulder. He always let it stay, but he stiffened his body each time. He suspected that it wasn’t possible that someone could look at him and not think he was a gullible pecker.

Nina gushed about the show on the drive home. She even went into how Berch had tricked Evan into believing that he had received a postcard in the mail from Keith Richards.

“Wasn’t that a beautiful thing for one person to do for another person?” she asked her sister, who said yes, it was. The only thing that Evan heard in Nina’s words was how immature he was for writing to Keith in the first place.

“Call me,” she said as Evan was getting out of the car.

“I will,” he said, knowing he wouldn’t.

Evan knew his dad was asleep so he used the key under the mat. As soon as Evan got to his room, he threw the postcard, frame and all, in the trash. His trash barrel was under a poster of Keith, whose arms were crossed hard against his chest, daring anyone in the world to call him a pathetic loser. Evan knew that Berch was as close to Keith as he could ever get.

Evan lay on his back on his bed and was aware of feeling trapped: in his room, in Somerville. The walls did seem to tip in at the ceiling now. It was as if the room had shrunk, exactly as Berch had predicted it would.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor. She writes occasional Best Forgotten columns for The Awl.

FAKES is The Awl’s year-end holiday series for 2017. You can read the whole collection here.