When Robots Write Our Emails

Crystal, Grammarly, and the automation of email.

Image via Pixabay

Crystal is refusing to take my calls, preferring the anonymous screen that email provides. And why would they, when the premise of their whole service is to provide a foolproof way to write better emails, and to, as their website claims, “help people understand and communicate with each other better at work and in life.” Crystal is a browser extension that mines your data—any social media profiles and your email inbox—to create a personality profile of your preferred communication preferences. In turn, it provides suggestions on tone, greetings, and content. Advice such as instead of writing “that’s fine” which may come off as disinterested, write: “that’s great.” Instead of the ambiguous “let me know” write: “let me know if you can make it by 5pm tomorrow.”

When I first email Luke, who works at Crystal, he emails back immediately prompting me to send him over any questions I had via email. When I suggest a phone call, he ghosts me. I give in and send over my questions and get a reply the same day. The whole time I’m wondering if Luke—or the browser extension, Crystal—can tell through my tone that I’m skeptical of the implications of such a service. I choose my words carefully. What parts of the email are Luke, and what parts are Crystal’s suggestions? I ask if an increasing emphasis on technology in the workplace will result in a program like Crystal becoming necessary to communicate with co-workers.

“We think technology has the potential to dramatically improve conversations at work by providing a ‘user manual’ on how people prefer to communicate. There’s so much time spent guessing how someone communicates and behaves. This ambiguity drains productivity and strains relationships. Why not just document your work style and share it with the people you work with?” Luke replies. Following up, he says: “With that being said, I don’t think technology will replace human-to-human conversations. We see our role as breaking down the barriers that currently exist.”

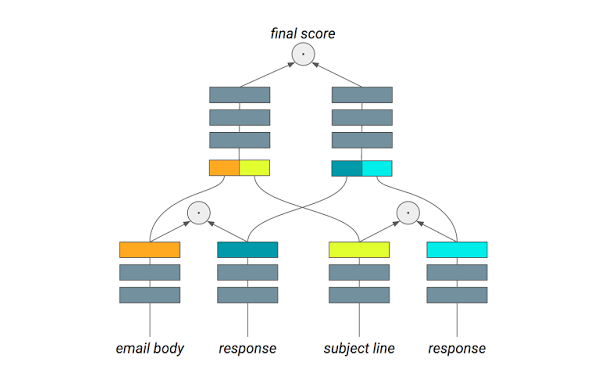

The hierarchy of email language, according to Google’s Research blog

But what if technology does replace human-to-human conversations? My Gmail app now provides predictions on how to answer any email received in four words or less. “Yes, that’s fine”; “Safe travels”; “No, thank you!” Stock phrases that can be used over and over, in a variety of situations, take the place of a personalized response. Communication via email is searching for an alternative to the labor-intensive human model, it’s looking to automate.

Buzzfeed writer Katie Notopoulos conducted an experiment where she responded to emails using Gmail’s auto responses in an attempt to reply to emails quicker, hereby not letting her unread emails to grow in the thousands. Notopoulos found that, “For that whole week, I felt extremely productive at work. And I was! I ended up publishing more articles than usual. There was an extra, unexpected effect—I felt less like I needed to check my email in the evening after work. Previously, at night I’d often catch up on email, especially personal emails that I had put off during the workday. No more!” Nowhere does she note if using Gmail’s auto-replies made her emails better, or if she received any replies to her emails. Gmail’s automated answers advocate for efficiency, not personality.

![]()

The lack of personality is epitomized in robots. I can’t help thinking about how a conversation between two people relying on Gmail’s auto-responses would proceed, at what point is the conversation more computer than human? A YouTube video, uploaded by Cornell Creative Machines Lab in 2011, shows two chatbots speaking to each other. The conversation quickly goes wayward, moving too fast, and ends in spite. The robots move rapidly away from pleasantries into the rocky territories of religion and mortality. At the core of the conversation is misunderstanding. “I’ve answered all your questions,” says Cleverbot. “No, you haven’t,” the second Cleverbot replies without skipping a beat. And then immediately after: “What is God to you?” This doesn’t inspire confidence in letting robots control the conversation for us.

An email correspondence that relies solely on predictive computer algorithms to create a response—as Gmail’s auto responses do—creates the possibility of ascending into meaninglessness; a conversation where nothing is actually said. While these predictive texts may be lauded as a better, more efficient, way to communicate, they can cumulate in the opposite: missteps and dialogue void of emotion.

Nowhere is this clearer than Facebook’s recent AI experiment where two chatbots were encouraged to negotiate how to split various items. The chatbots, left to their own devices, eventually abandoned English and began to communicate with each other in an untranslatable language:

Bob: i . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Alice: balls have zero to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to

Bob: you i i i i i everything else . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Alice: balls have 0 to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to

Bob: you i i i everything else . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Alice: balls have zero to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to

My prediction is that if two humans rely on premeditated text algorithms, and the more subtle suggestions of services like Crystal, that the conversation would quickly crumble. If I continuously replied with Gmail’s suggestions, and Luke replied using Crystal’s services, would we not hit a dead-end in the conversation quickly?

![]()

I labor and stress over important emails, and therefore have made myself a set of email rules to follow. I refer to the person by the name they sign off with, I limit myself to one exclamation mark per email, I sign off with all the best and mean it. In an essay for Catapult the writer Marissa Febos asked, “Do you want to be known for your writing, or your swift email responses” and my answer is: can I be known for my swiftly sent, well-written emails?

Maybe the creator of Crystal feels similarly. Drew D’Agostino, a software entrepreneur from Nashville, founded Crystal in 2014 “to fix the communication problems that arise when two people fail to understand their personality differences, especially over email,” according to Crystal’s about page. Before that, D’Agostino founded Attend, a company that works to increase marketing and sales at events by allowing companies to optimize their guest lists and track sales that result from said guests. A video on Attend’s website describes a smartphone app that provides alerts for when important “top prospective customers” enter the party with notes on who they are and what to talk to them about. What both of D’Agostino’s companies—Crystal and Attend—have in common in the streamlining of human interaction with technology.

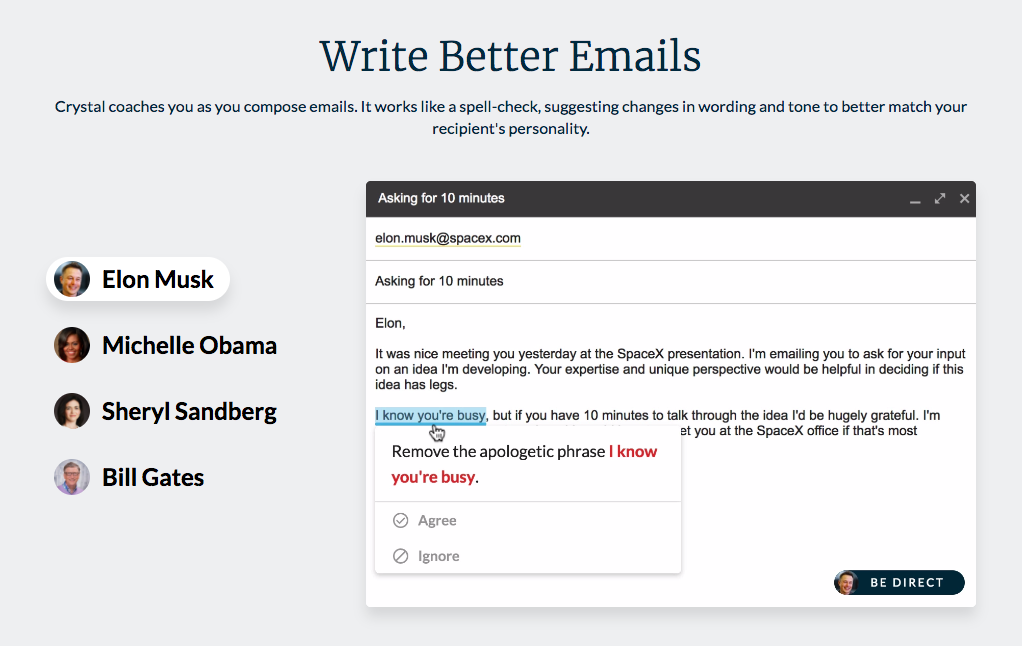

Screenshot via Crystal

One of Febos’s tips to counter the impulse to reply to each email graciously is: “Stop apologizing for taking a reasonable length of time to respond to an email.” I add this to my growing list of email rules, and only apologize for emails when I have truly messed up. In curating a growing list of rules in my head, I am, in a way, creating an analog version of what AI email plug-ins do. Or rather: the email plugins are doing what I already do, creating one less thing to think about.

I am constantly shifting my tone to meet the needs of recipients, creating a code that’s both friendly and professional. Crystal automates this thought process. When drafting an email a banner on the side contains Crystal’s email coach with tips aligning to the person you’re emailing personality type, such as “Be Casual” and “Keep the Subject Under 7 Words.” Tailored specifically for business emails, next to the “Send” button is a new button: “Be Brief” which cuts all extraneous sentences and words from your email.

When Luke emails a screenshot of what Crystal says about me, I can tell by the green circle in the far right-hand corner of his email that he’s also using Grammarly. If Crystal is a top editor, offering line edits and suggestions on how to change your wording, Grammarly is the copy editor, correcting spelling and grammar as you write. In theory, the combination of the two would render your emails immaculate, packaged and shiny. But how accurate are these programs? Grammarly routinely reminds me to add or take away commas, and catches typos. But it also misses nuances and awkward sentences that can only be vetted by a person re-reading and editing. Recently I wrote in an email: “I’m not sure if ARCs for her book are out yet (it comes out May 2018).” Grammarly coaxed me to changed “are” to “is” assuming the subject is “her book” and not “ARCs”. The extension often makes small mistakes like this, not recognizing the proper subject/verb possession, and then has the audacity to send me an email noting that my top mistake is “verb form”.

Screenshot via Grammarly

If Crystal mines the data of how I present myself via LinkedIn or Twitter, which are performative and situational representations of a version of myself I want to present to the world, how accurate can it be to who I truly am and what type of email I would like to receive? Artificial intelligence is only as smart as the humans who use it, in other words: not very smart at all. A new study from AI Now Institute of New York University shows that AI is absorbing the biases that humans hold, resulting in a not only flawed but dangerous dystopia. Will Knight, a senior editor for AI at the MIT Review writes, “If the bias lurking inside the algorithms that make ever-more-important decisions goes unrecognized and unchecked, it could have serious negative consequences, especially for poorer communities and minorities.”

Letting robots speak for us when they’ve adopted racist tics of society will perpetrate similar views. A 2017 press release from AI Now Institute warns: “The consequences of incomplete or biased systems can be very real. A team of journalists and technologists at Propublica demonstrated how an algorithm used by courts and law enforcement to predict recidivism in criminal defendants was measurably biased against African Americans

But even if email automation has its faults, it persists in automating a part of our lives that has become strenuous. Communication via email has become riddled with anxiety—a growing inbox number that seems impossible to tackle is solved by Gmails automated services, an embarrassing typo is caught by Grammarly, stressing over the tone of a business correspondence is made easier by Crystal. People are willing to accept AI’s flaws, and forsake their privacy by handing companies email data, to alleviate the stress of technology.

While communicating through an automated middleman reeks of the impersonal, email automation programs make up for it by creating personalized profiles with statistics on how you interact. Essentially gamifying—creating scores akin to one you’d receive in a video game—human interaction, creating incentive to continue using the services. I can’t help but ask Luke what Crystal says about me from my social media presence and emails. He replies with a couple of screenshots of Crystal in action, which says I’m a “decisive creative influencer.” All of a sudden, I’m sold. Grammarly sends me a weekly round-up of my “stats” which declare I’m more productive than 92% of Grammarly users, and use 93% more unique words. User stats and complementary profiles further the gamification of these plugins, not only gaming the way you communicate with others but turning your own set of everyday actions into quantifiable data.

![]()

Erin Gee, a media artist living in Montreal, was a beta-tester for Crystal. On agreeing to give the program access to her email archive she remembers a sudden sinking feeling of having given up her privacy (Marshal McLuhan’s “womb-to-tomb surveillance”). “The profile that they built of me was really disappointing, for one thing, they said something to the effect of ‘Erin is very sarcastic.’ I found that really nerve-wracking to think that if I ever work for a corporation or someone who uses this software, I don’t think sarcastic is something you want in a future employee or to collaborate with, it doesn’t sound very positive at all.” (I’ve emailed with Erin, and never felt she was sarcastic.) Erin continued, “It’s hugely Orwellian, because now before you behave on the internet you have to be like wait: If I behave that way, will an algorithm think I’m sarcastic?”

Even though Crystal is free, I can’t bring myself to sign up. Luke has an optimistic view of the way people use the program: “Many people will take a personality test and forget to apply the learnings. Crystal helps reinforce and apply this mindset to everyday conversations.” But do we really need a computer program to remind us that everyone is different? Gee doesn’t think so. “What could be less empathetic than a machine telling you how to game your interaction with someone?”

The first image you see when visiting the website for Crystal is an image of a man and a woman sitting on a couch smiling at a Macbook. In the URL, crystalknows.com, the “knows” feels sinister. As if I’m being watched, and I guess I am. In the photo, it appears as if the couch is sinking in at the center; that the laptop is the center of gravity, pulling the viewers in.