Fuchsia, The Pinky Purple of Victorian Gardens and "Miami Vice"

Cultural histories of unusual hues.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

When I was a little girl, I got in trouble for flower-related crimes, like stealing the neighbors’ flowers, ripping up a lady slipper by her roots, and (my most minor but most common infraction) methodically popping the fuchsia buds that hung over our patio, squeezing them one-by-one until they opened with satisfying little sighs. When closed, fuchsia look like hot pink orbs, but when you apply a slight amount of pressure, those four long hot pink sepals open to reveal a cluster of purple petals that surround the sex organs of the plant (the baby pink pistil and stamen). There’s something slightly erotic about this action. Even famed recluse Emily Dickinson once noted the mildly hedonistic joy of popping fuchsia: “I tend my flowers for thee– / Bright Absentee! / My Fuchsia’s Coral Seams / Rip–while the Sower–dreams”.

Although fuchsia was “wildly popular” in the Victorian era, according to Judith Farr’s book, The Gardens of Emily Dickinson, it’s no longer as ubiquitous in gardens. I have such vivid memories of popping fuchsia as a child, but I can’t recall the last time I saw a hanging basket of fuchsia. It turns out that fuchsia—both the color and the plant—is something that slips in and out of fashion, peaking suddenly before sliding back into obscurity. Unlike the ever-popular Prussian blue or the enduring appeal of crimson, fuchsia is an uncommon color that few people list as their favorite. (Though perhaps this is because it’s damn near impossible to spell.)

These erotic tropical blossoms first appeared in European gardens around 1700 thanks to Charles Plumier, a French monk and botanist who “discovered” over 4,000 plants in the Caribbean islands and South America. “In 1695, during his third voyage, while on the lookout for the Cinchona tree (quinine) on behalf of King Louis XIV, [Plumier] discovered, sketched and described a new plant he found on the foothills of Hispaniola (nowadays Haiti and the Dominican Republic)” writes Manhattan-based fuchsia enthusiast R. Theo Margelony on his blog Fuchsias in the City. In 1703, Plumier publicized this new plant, naming it officially Fuchsia triphylla, flore coccineo, in honor of Leonhard Fuchs, a German physician and botanist who Plumier really admired. Fuchsias quickly became popular in gardens throughout Europe, prized for their bright color and distinctive shape. They also earned the nickname Lady’s Eardrop, for its supposed resemblance to an unattached lobule.

Fuchsia the color was named after fuchsia the flower, which was named after a German fellow with the last name Fuchs (meaning “fox”). Given that history, it should perhaps be pronounced FOOKS-sia, but it’s not. It’s FEW-shuh. Fuchsia is one of the most commonly misspelled plant names, next to ginkgo, according to Ken Thompson, author of The Skeptical Gardener. “Google finds 65.1 million hits for fuchsia, but still a respectable 14.4 million hits for fuschia,” he points out. He suggests that, should you be stuck trying to remember how to spell it, simply repeat to yourself “fooksia” and you’ll be fine. That works, but not quite as well as the suggestion offered up by web comic XKCD. “Think of it as fuck-sia.”The color fuchsia was born in the mid-1800s, after decades of what Victoria Finlay calls “mauve fever” in Europe (which an English journal of the time referred to as “Mauve Measles”). Following the success of puce and the explosion of mauve, European fashion was primed for a new hue, particularly one in the pink or purple family. In 1859, French dye manufacture Renard Frères et Franc began selling an intense, dark red coal tar dye named “fuchsine” after the flower. But it was “too easy to mispronounce,” Finlay explains, “and it got better sales when renamed after a battle that year in the town of Magenta in northern Italy.” While the renaming didn’t stick, fuchsia and magenta are still considered alternate names for the same color, even though the color itself has changed over the centuries.

By Globe Collector – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

After a brief falling out of favor, fuchsia re-emerged in the 1890s and was “heralded from newspapers as being among the most fashionable of new hues for ladies’ dresses and hats,” writes Margelony on Fuchsia in the City. (A quick note: Fuchsia in the City is probably the greatest website I’ve ever come across. It’s hyper-focused to the point of obsession, and filled with funny articles about fuchsia history and fuchsia gardening tips—he even makes fuchsia fact memes for twitter. What a guy!) As Margelony explains, the fuchsia popular in the late 1800s was a particularly reddish form of the color—hot pink, yes, but with a tomato-y undertone. This color was particularly visible at the Grand Pix de Paris of 1893, but fuchsia’s time in the spotlight didn’t last long. In 1894, a reporter said the reddish purple as “now considered rather passé by fashionable people.” Fuchsia was gone as quickly as it came.

Fuchsia lay dormant for a few years as other colors dominated the fashion cycle, only to emerge again with the arrival of the flapper, but this time it had some new associations. “The new magenta/fuchsia of the modern age is much more daring and alive than that old fuchsia could never had been in its age of corsets and bustles,” Margelony writes. “It was brash and frankly uninhibited. It was a bit naughty… The Roaring Twenties finally roared off into the Thirties on even-stronger chrome and black, highlighted with hues like cobalt and turquoise and bright, sexy fuchsia.” It soon became a popular color for negligees and underthings.

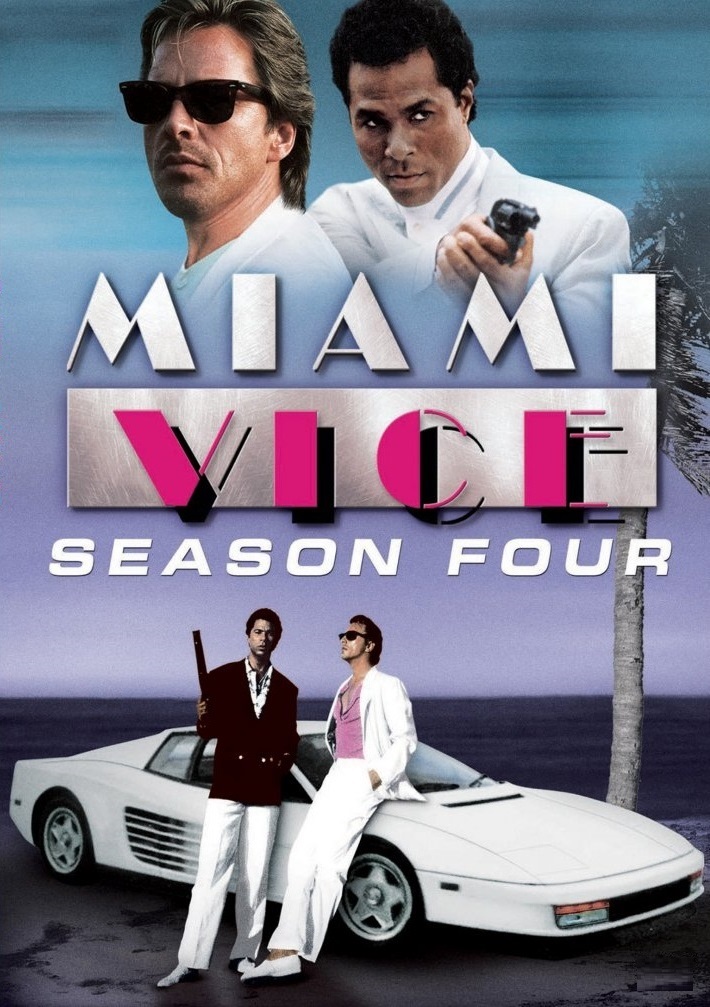

It continued to pop up periodically throughout the 20th century in women’s fashion but the gendered nature of the hot pink hue shifted slightly in the 1980s. In 1985, Los Angeles Times ran an article titled “Pink Is for Pussycats—and the Tough-Guy Cops on ‘Miami Vice’” that reported on the “costliest, flashiest, trendiest men’s clothing ever seen on small screens.” One notable outfit was composed of an “aqua suit with a fuchsia shirt, a turquoise tie, a pale pink belt and white shoes.” According to Jennifer Grayer Moore, author of Fashion Fads Through American History, the popular TV show caused a short-lived “infatuation with Floridian chic,” a style that leaned heavily on two tropical colors: fuchsia and teal.

The fuchsia of the MTV generation (and a few years later, the “Sex and the City” crew) is not the same color as the fuchsia invented in 1800s France. The name fuchsia has stuck, as has the general idea of it—a bright, purplish pink—yet fuchsia has become ever brighter as the years wore on. What the Victorians called fuchsia is slightly duskier than the contemporary color, a little browner, a little more muted (this color still exists, and is often labeled as “antique fuchsia”). Late nineteenth and twenty-first century fuchsia is made from equal parts blue and red and it is bright, bright, bright—almost blindingly so. Fuchsia is a vital part of the color printing process, one of four ingredients in the CMYK color model. In web design, fuchsia and magenta are considered interchangeable and can be found under the hex code #FF00FF, though it is not used terribly often. (Purple and hot pink are two of the least popular colors in web design.)

But though fuchsia is relatively rare online, the digital world has influenced how people understand this complicated color. In 2009, a video about color mixing and how our eyes perceive colors went viral, spawning dozens of articles proclaiming “magenta doesn’t exist!” and a briefly lived twitter meme about the color. Since fuchsia/magenta is an extra-spectral color—i.e., one that isn’t found on the rainbow of visible light—some people began to think it was “all a lie.” But the truth is that fuchsia, like all other colors, exists only in our heads. We perceive fuchsia as a total absence of green, which is why, should you stare at a green light long enough, Gatsby-style, you’ll be rewarded when you look away with a fuchsia afterimage. It’s real, but it also exists only in your head. How’s that for a hot-pink mindfuck?