Tasting The Devil

The Awl’s holiday series on flavors and spices.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The “ouzo effect,” or “louche effect,” takes place when you pour water into one of the aniseed boozes. These are raki, pastis, ouzo, absinthe, arak, and sambuca. The liqueur begins clear or slightly colored (green, in absinthe’s case) but upon contact with water it turns a milky white as if transmogrified into the semen of the devil. This phenomenon occurs because the essential oil trans-anethole, also known as the flavoring compound anise camphor, is strongly hydrophobic: the oil has been dissolved in alcohol but when water is introduced it freaks out, turning the liquid opaque.

The association between aniseed and opacity feels spiritually right, because the merest whisper of aniseed on the air turns my world into a black void composed entirely of disgust. It is a total phobia. Trans-anethole is essentially what we know as anise, but it also gives that characteristic flavor to fennel, licorice, camphor, magnolia blossoms, and star anise. Fennel in a salad? No. The German candy Pfeffernusse? Fuck you. Licorice mixed in with normal candy? Cut my throat, rather.

Aniseed essential oil comes from the plant anise, Latin name Pimpinella anisum. This is not the same plant as star anise, which I can tolerate, or Japanese star anise (Illicium verum and Illicium anisatum, respectively), although those unrelated spices do also contain anethole. Growing in the eastern Mediterranean and in Southwest Asia, the name “anise” derives from the Arabic word yaānsuūn (“يَانْسُون). It is a herbaceous annual plant which grows about a meter high. The fruit of the plant is a schizocarp, which is a dry thing that splits into multiple carpels after falling.

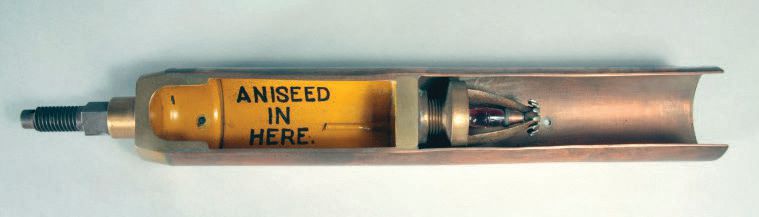

The anise plant has a long history of medicinal use. The sixteenth century botanist John Gerard recorded that it could help with flatulence and also “stir up lust.” In the nineteenth century a Civil War nurse named Maureen Hellstrom tried to use anise seeds as an antiseptic. This was poisonous and did not carry on for long. Fishermen put anise on their lures to attract fish. British steam locomotive engineers put aniseed oil capsules into their metal ball bearings which broken when overheated, warning the driver with “the unmistakable smell of the fluid.”

Photo courtesy of the National Railway Museum.

Part of my phobia has to do with my drunken adolescence. In the dwindling years of the last decade I woke with sticky elbows about twice a week. In student clubs and cheap pubs across the United Kingdom, it is normal for the entire bar to be coated in a half-evaporated layer of sambuca. I’ve never quite understood why this aniseed-flavored liquor is so popular with British students, but it is. When the dreaded black plastic tray heads your way, laden with shots and borne aloft in a cheerful hand, you can pray for tequila but God does not listen.

But the phobia is older than that, dating back to a primordial licorice experience. I call it a phobia because the reaction of my tongue and throat and whole puking apparatus to aniseed is more than disgust. It is a physical recoiling that I can only liken to the feeling on your tongue when you accidentally taste deodorant. Aniseed is less a flavor to me than a spectrum of revulsion, the way that rot can taste like mould or like death or like the sweet breath of a destitute alcoholic.

Aniseed tastes to me like marzipan and parma violets and soap and cardamom and aluminium and obligation. It tastes like forcing your vomit down out of politeness when somebody elderly and kind gives you something disgusting. It tastes like the texture of powder and the involuntary gag that follows your fourth shot (I hate it, so much, and yet I’ve drunk so much sambuca). It tastes like talcumy old ladies and pissing on your shoes in an alley. It tastes like the billowing dark of a blackout and a hundred-year-old jar of sweets, each one laced with poison by an evil old woman.

Image: Richard Riley via Flickr

So, my deepest disgust has three chief elements. There’s the flavor profile of anise camphor, which is a material fact of the botanical universe. There is the world of aniseed sweets, which go along with the memory of being made by adults to eat what I did not want to eat. And then there’s the alcohol, and the accident of my birth in boozy England. Put together, aniseed is a pillar of my sensory being. Historically and geographically contingent, yes, but that is what our sensory identities are all about.

I’m not sure I know anybody else who hates aniseed this much, nor do I think that my interpretation of the anise essential oil flavor is right any more than the natural fact of the ouzo effect is right. Instead, my disgust simply testifies to the existence of the world as I see it; a world of tastes which I can access through my tongue alone. Like love, hate is a subjective experience that returns you to your body, alone in your feelings but certain of them. Aniseed is my certainty. It’s good to know what you do not want in your mouth.