Luddites Are The Working-Class Halloween Monsters We Need

How to scare friends and alienate corporations.

Forget the neutered idea of a Luddite as someone who avoids computers, who tells you to stop using your smartphone. The real Luddite is one erased from history. As E.P. Thompson wrote in The Making of the English Working Class, “I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the ‘obsolete’ hand-loom weaver, the ‘utopian’ artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcutt, from the enormous condescension of history.” Luddite has long been used as a dismissive term, but there’s a subculture of history buffs who have tried to repair their memory, including one Jonathan Franzen.

The Kraus Project, Franzen’s 2013 translation of essays by Karl Kraus, the Austrian satirist, is peppered with footnotes. “Not only am I not a Luddite,” Franzen writes, “I’m not even sure the original Luddites were Luddites. (They had no systematic beef with technology; it simply seemed practical to them to smash the steam-powered looms that were putting them out of work . . . I don’t mind technology as my servant; I mind it only as my master.” He hated when “Twitter addicts” called him a Luddite. His response: “Nyah, nyah, nyah!” Which might double as a Luddite blearing at midnight. With Franzen’s blessing, or not, it’s time to return to the original spirit of the Luddite legend.

In 1779, young Ned Ludd broke into a Leicestershire home and smashed two stocking frames, machines for knitting hosiery. His “fit of insane rage” inspired Lord Byron to write verse in appreciation: “As the Liberty lads o’er the sea / Bought their freedom, and cheaply, with blood, / So we, boys, we / Will die fighting, or live free, / And down with all kings but King Ludd!” Even Thomas Pynchon has sung Ludd’s phrases, calling him not a single-minded madman, but a “Badass,” whose machine-busting was more than uncontrolled rage. Ludd was smashing machines that had existed since the 16th century. His real enemy was automation: what Pynchon describes as “the ability of each machine to put a certain number of humans out of work—to be ‘worth’ that many human souls.”

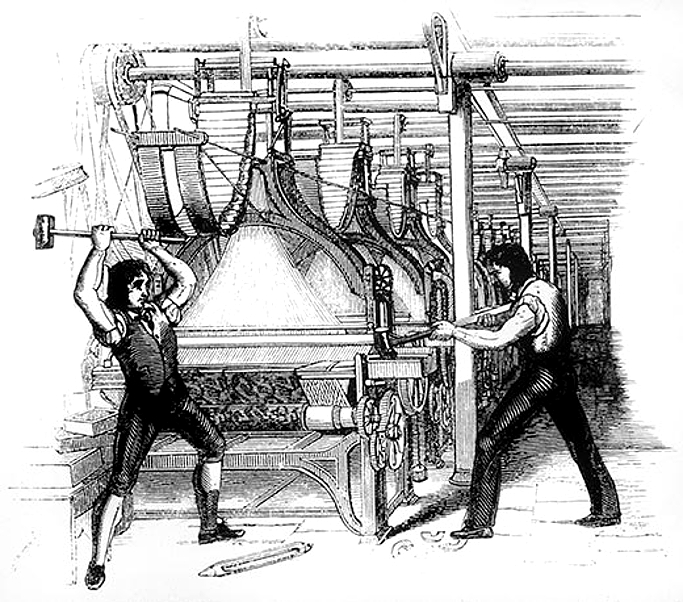

Poor wages, shoddy goods created by machines, and the threat of lost jobs led English textile workers to channel the Ludd legend in 1811. Eric Hobsbawm called their actions “collective bargaining by riot.” At night, they smashed machines with sledgehammers in Yorkshire. They burned factories. They penned threatening, maniacal letters, like this one from 1812:

Take notice that a Declaration was this Day filed against you in Ludd Court at Nottingham, and unless you remain neutral judgement will immediately be sign against you for Default, I shall thence summon a Jury for an Inquiry of Damages, take out Execution against both your Body and House, and then you may Expect General Ludd, and his well organised Army to Levy it with all destruction possible.

Another letter calls its recipient “one of those damned miscreants,” and has given orders for the man to be “shot through the body with a Leden Ball.”

One long letter ends with a promise: “We petition no more—that won’t do—fighting must.”

Luddites were wild, they were many, they were one. They were the generations of poor workers who did not hate the machines, but hated the men who used those machines to steal money from communities.

What would be more frightening—what would be truer—than the vigilante of darkness, the Luddite? The Luddite is the monster and scourge of unfeeling corporations, and those intent on using—and then disposing—of souls for profit. The Luddite is the perfect melding of the supernatural and the prosaic: a spirit who is here to answer for those who have been taken advantage of, and to do so with a wallop and crash.

If you want to get someone thinking this Halloween, dress like a 19th-century weaver, drag a machine into a field, and get swinging. Hang a sign on the mechanical corpse that says “Ned Ludd did it,” and then go hand out some candy. You might want to save your labor lessons for the parents waiting in the street. But a little rage against the machine during the one night of the year when we drift from house to house, open to old mysteries and truths, could do us some good.